Exaggerating the importance of affirmative action

- Share via

Supporters of affirmative action breathed a nervous sigh of relief last week when the Supreme Court essentially punted on a case that some had feared would have led to a gutting of racial preferences in admissions to state universities. But even if the court had declared such preferences unconstitutional, it doesn’t follow that enrollment of minorities in higher education would have plummeted. Most colleges aren’t highly selective.

The political and legal debate about racial preferences is basically about a small sliver of highly competitive institutions. That was underlined by an article in The Times on Sunday about minority enrollment in California’s state universities, which are prohibited from engaging in racial preferences as the result of a 1996 ballot initiative known as Proposition 209.

The article noted that the percentage of African American freshmen at UCLA dropped from 7.1% cases in 1995 to 3.6% last fall. At UC Berkeley, African Americans made up 6.3% of freshmen in 1995 and 3.4% last fall. But across UC campuses overall, “the enrollment of blacks has nearly recovered to its levels before Proposition 209.”

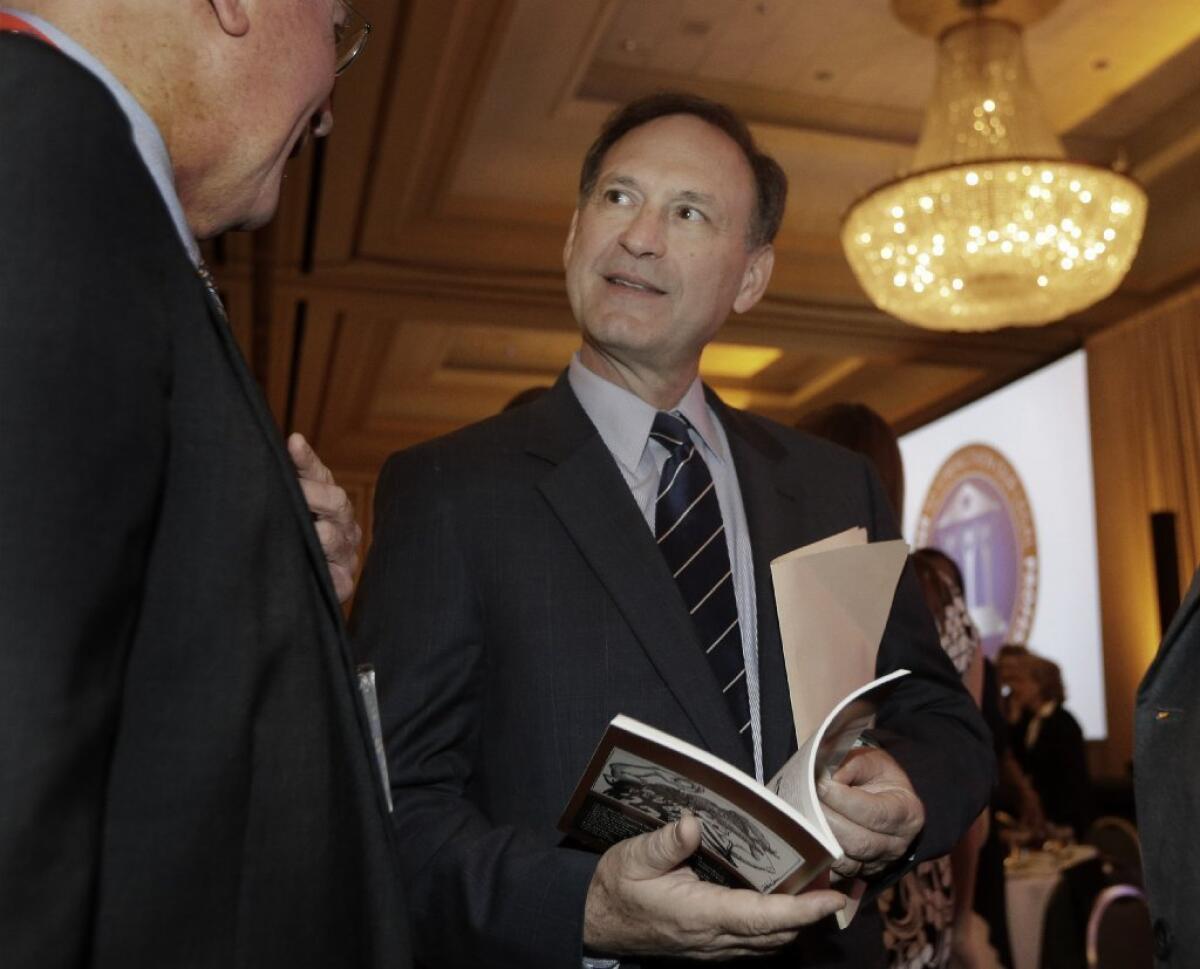

Those statistics reminded me of an exchange during the oral arguments in the Texas case between Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr. and Solicitor General Donald Verrilli. Alito questioned the Obama administration’s assertion that racial preferences at the University of Texas were necessary because the U.S. military relied on ROTC programs in assembling a racially diverse officer corps.

“So you’ve got a marginal candidate who wants to go to the University of Texas at Austin and is also interested in ROTC.” Alito said. “Maybe if race is taken into account, the candidate gets in. Maybe if it isn’t, he doesn’t get in. How does that impact the military?

“The candidate will then probably go to Texas A&M; or Texas Tech? Is it your position that he will be an inferior military officer if he went to one of those schools?”

Verrilli said no, but he didn’t grapple with the implication of Alito’s question: that a student doesn’t have to attend the University of Texas at Austin -- or UCLA -- to receive an education that will prepare him for leadership in the military or any other profession.

But maybe it’s Alito who misses the point -- that a small number of elite state universities (and elite private ones) educate a hugely disproportionate number of future leaders, and that where someone went to school is sometimes more important than how he or she performed there. Affirmative action aside, that’s a troubling proposition.

Perhaps a better way to promote diversity in society at large is to challenge the assumption that graduates of the University of Texas at Austin -- or UCLA -- have a lifetime advantage over the products of less-prestigious institutions.

ALSO:

Five reasons to stay away from Texas right now

Vatican infighting: We told you two popes could be a problem

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.