Going too far on DNA searches

- Share via

The Supreme Court erred grievously this year when it permitted Maryland police to collect DNA samples from people who had been arrested and charged with serious crimes — samples that could then be used to match that person’s genetic profile with evidence from unrelated unsolved crimes. As Justice Antonin Scalia pointed out in a scathing dissent, the 5-4 decision upholding Maryland’s law undermined the 4th Amendment’s ban on “searching a person for evidence of a crime when there is no basis for believing the person is guilty of the crime.”

When the decision came down, it was widely assumed that it also disposed of constitutional objections to a similar program in California. Last week, a lawyer for the American Civil Liberties Union told the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals that wasn’t necessarily so. Indeed, the appeals court could rule in good conscience — and without defying the Supreme Court — that California goes too far.

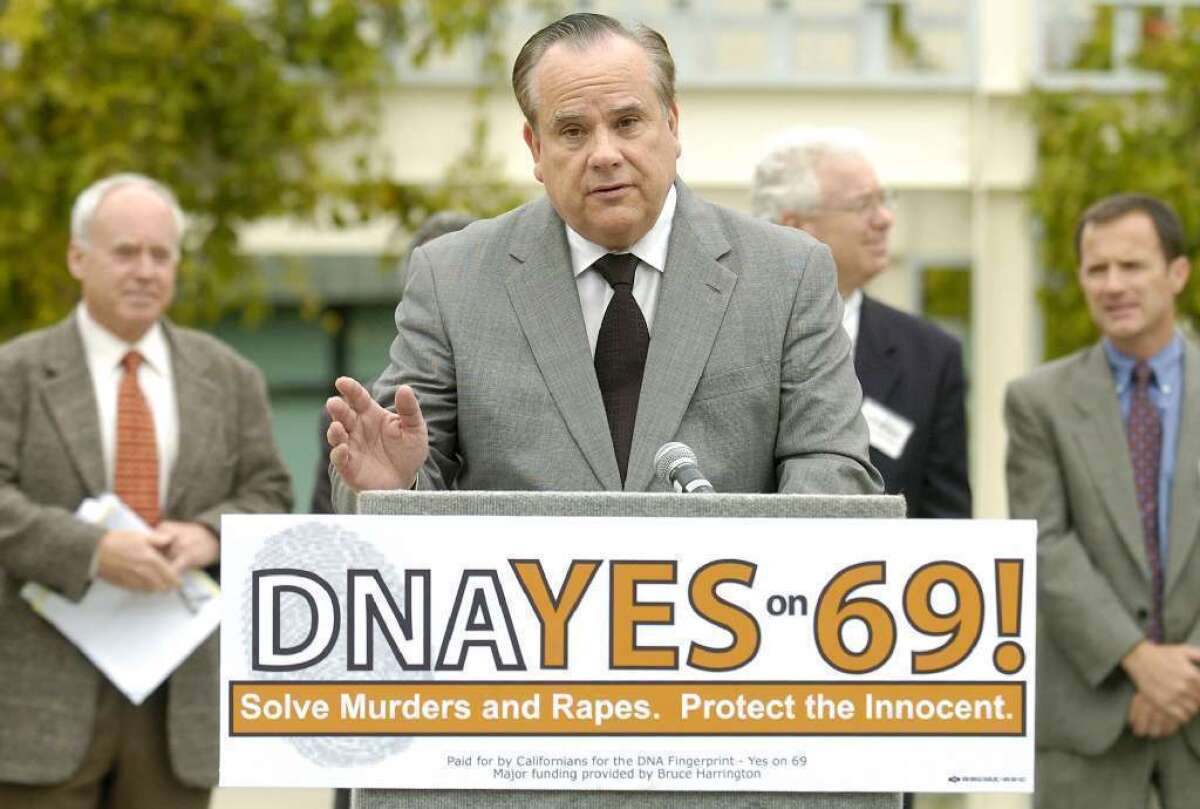

Under Proposition 69, approved by California voters in 2004, DNA evidence is collected from anyone arrested on suspicion of a felony. Someone who is arrested but ultimately not charged — or who is acquitted at a trial — can petition to have his DNA profile expunged from databases, but by then the information could have been compared to evidence from other crimes. This page opposed Proposition 69, arguing that the state shouldn’t be able to engage in fishing expeditions using the DNA of people who haven’t been convicted of a crime.

YEAR IN REVIEW: Highs, lows and an ‘other’ at the Supreme Court

Lawyers for those who are challenging Proposition 69 called the 9th Circuit’s attention to several differences between Maryland’s law and California’s. For example, in Maryland, police may not analyze or match a DNA sample until a judge determines that there is probable cause to believe that the suspect has committed a serious felony; California has no such requirement in its law. That’s one reason, the lawyers say, that the California law may be unconstitutional even though the Maryland law has been upheld.

Lawyers for the state counter that the differences between California and Maryland systems are not constitutionally significant and that the Supreme Court made it clear that collection of DNA was simply part of the booking process, like fingerprinting. It’s true that Justice Anthony M. Kennedy’s majority opinion treated DNA collection as a form of identification rather than an investigative tool. But a decision by the 9th Circuit striking down Proposition 69 might force him to confront the reality that the intrusive “search” in DNA collection isn’t the acquisition of the sample but the gathering (and storage) of the personal data of people who have not been convicted of wrongdoing in order to link them to unrelated crimes.

Supreme Court decisions are the law of the land, and inferior courts can’t contradict their holdings. But if the 9th Circuit agrees that California’s DNA collection system poses special dangers to the privacy rights of people who have been arrested, it should say so and give the Supreme Court an opportunity to revisit the larger issue.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.