Shielding journalists, by law

- Share via

After a firestorm of criticism, the Obama administration is suggesting that it will make amends for its aggressive pursuit of journalists suspected of receiving leaks of classified information. But airy affirmations of the importance of a free press and vague promises of a new look at Justice Department regulations aren’t enough. The administration needs to commit itself in specific terms to stronger protections for news gathering that will be embodied in a federal statute.

It was bad enough that the Justice Department seized the records of calls from more than 20 telephone lines belonging to the Associated Press and its journalists without notifying the news agency in a timely fashion — or giving the AP the chance to object in court. But then, last week, it was revealed that in an entirely separate leak investigation, federal agents read the emails of a Fox News reporter. They obtained a warrant for James Rosen’s emails by asserting that there was probable cause to believe he had violated the Espionage Act. (Using subpoenas, investigators also obtained Rosen’s phone records.)

Despite its name, the Espionage Act outlaws not only spying for foreign enemies but the unauthorized receipt or transmission of “national defense” information. The Justice Department over the last five years has prosecuted six government employees for violations of the act (including Army Pfc. Bradley Manning, who is undergoing a court-martial). But until the revelation about the Rosen investigation, there was no suggestion that the Obama administration would depart from the practice of previous administrations and accuse journalists engaged in doing their jobs of violating the act.

In applying for a search warrant for Rosen’s emails, an FBI agent described the reporter as an “aider, abettor and/or co-conspirator” because he asked State Department security contractor Stephen Jin-Woo Kim to share secret material. Apparently, information provided by Kim was the basis of a Fox report suggesting that North Korea would respond to a U.N. Security Council condemnation with another nuclear test.

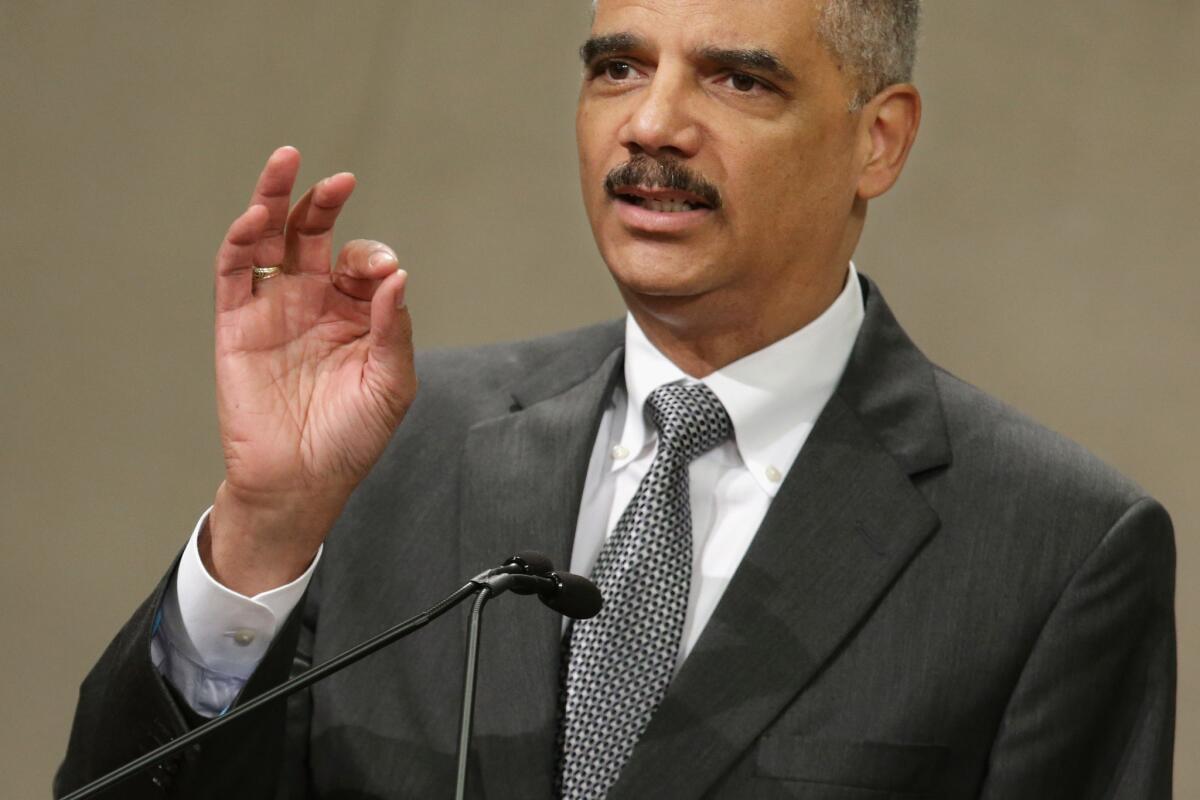

In his speech on terrorism last week, President Obama implicitly criticized the Justice Department’s actions in the Rosen case, saying: “Journalists should not be at legal risk for doing their jobs.” He also reaffirmed his support for a “shield law” to protect confidential communications between journalists and their sources and said that he would ask Atty. Gen. Eric H. Holder Jr. to review Justice Department regulations and report back by July 12. Holder, who approved the warrant for Rosen’s emails, has acknowledged that “both our laws and guidelines need to be updated.”

He’s right. Current Justice Department guidelines say that before issuing a subpoena for journalists’ records, the department’s attorneys “should take all reasonable steps to attempt to obtain the information through alternative sources or means.” That protection should be stronger, requiring that other possible sources be “exhausted.” And while the guidelines instruct the department to negotiate with journalists before issuing subpoenas for phone records, there is a vaguely worded exception for situations in which negotiations would “pose a substantial threat to the investigation.” Apparently the government relied on that in refusing to give the AP timely notice that it had obtained its phone records. We see no reason for that exception.

Even if the regulations are strengthened, there is always the danger that Justice Department attorneys in this or a future administration will find a way to circumvent them. That is why Congress must enact a shield law that requires government investigators to obtain a judge’s permission before seeking information from journalists that would compromise a confidential source. Though different in some respects, bills recently introduced in the House and the Senate would accomplish that objective (and also require that the department exhaust “all reasonable alternative sources” before seeking information from journalists).

Previous administrations have recognized that the 1st Amendment contemplates a division of labor in which government may seek to keep information secret while the press sets out to uncover secrets in its efforts to keep the public informed about the actions of its leaders. In its zeal to plug leaks of classified information, the Obama administration upended that traditional understanding. It must show by deeds as well as words that it recognizes where it went wrong.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.