Disclosure and democracy

- Share via

In its reckless Citizens United decision in 2010, the Supreme Court divided 5 to 4 in holding that corporations could spend unlimited funds to influence elections. But in the same case, eight justices agreed that it was constitutional for Congress to require disclosure of the identities of those who paid for political advertising.

In a part of his opinion joined by every member of the court except Clarence Thomas, JusticeAnthony M. Kennedy wrote: “The 1st Amendment protects political speech; and disclosure permits citizens and shareholders to react to the speech of corporate entities in a proper way. This transparency enables the electorate to make informed decisions and give proper weight to different speakers and messages.”

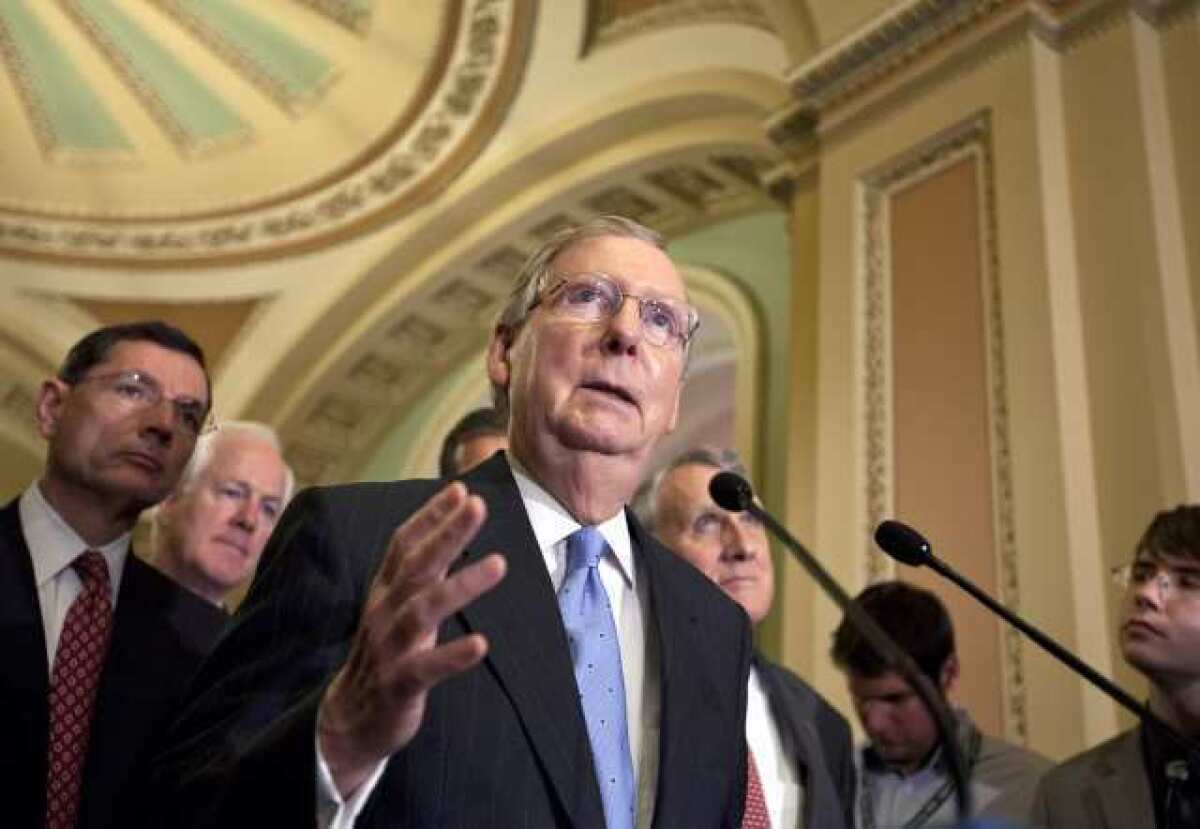

Don’t tell that to Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.). In a speech to the American Enterprise Institute on Friday, McConnell claimed that the authors of the proposed DISCLOSE Act, which would strengthen disclosure requirements for political expenditures, are part of an “effort by the government itself to expose its critics to harassment and intimidation.”

McConnell said that the billionaire brothers Charles and David H. Koch, because they are known to support conservative causes, “have had their lives threatened, received hundreds of obscenity-laced hate messages and been harassed by left-wing groups.” President Obama has abetted these tactics, McConnell said, by accusing the Kochs of being part of a “corporate takeover of our democracy.”

Like Thomas, who in his Citizens United opinion cited supposed death threats against supporters of Proposition 8, McConnell seems to believe that not only the ballot must be secret; so must the identities of people and corporations that flood the airwaves with attack ads.

McConnell likened such donors to the Alabama NAACP, which was allowed by the Supreme Court in 1958 to withhold its membership list from segregationist state officials. In his dissent in the Citizens United case, Thomas cited another case in which the court protected anonymity: a 1995 ruling upholding the right of a citizen to distribute anonymous leaflets about a tax referendum.

More recently, however, the court has emphasized disclosure. In a 2010 case involving a Washington state referendum on domestic partnerships, it ruled that, as a general matter, states could publicize the names of voters who signed petitions to place a question on the ballot. That ruling did leave open the possibility that the court would block a particular disclosure if there was a “reasonable probability” of “threats, harassment or reprisals.” But when the Washington plaintiffs returned to the court with specific allegations of harassment, the justices declined to hear the case.

At the oral argument in the original Washington case, Justice Antonin Scalia said that “the 1st Amendment does not protect you from criticism or even nasty phone calls when you exercise your political rights to legislate or to take part in the legislative process.”

Scalia’s right. McConnell needs to recognize that disclosure and democracy go together.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.