The audacity of democracy

- Share via

Monday marks the 225th anniversary of the turning point of the world — the hinge of modern human history.

On Sept. 16, 1787, kings, czars, sultans, princes, emperors, moguls, feudal lords and tribal chieftains dominated most of Earth’s landmass and population. Wars and famines were commonplace. So it had always been. Democracies had existed in a few old Greek and Italian city-states, but most of these small-scale republics had winked out long before the American Revolution. While Britain had a House of Commons and a broad-based jury system, hereditary British kings and lords still retained vast powers. A small number of Swiss yeomen governed themselves, and the Dutch republic was on its last legs. That was about it for democracy in the world.

Today, roughly half the planet lives under democracy of some sort. What happened to precipitate this stunning global transformation?

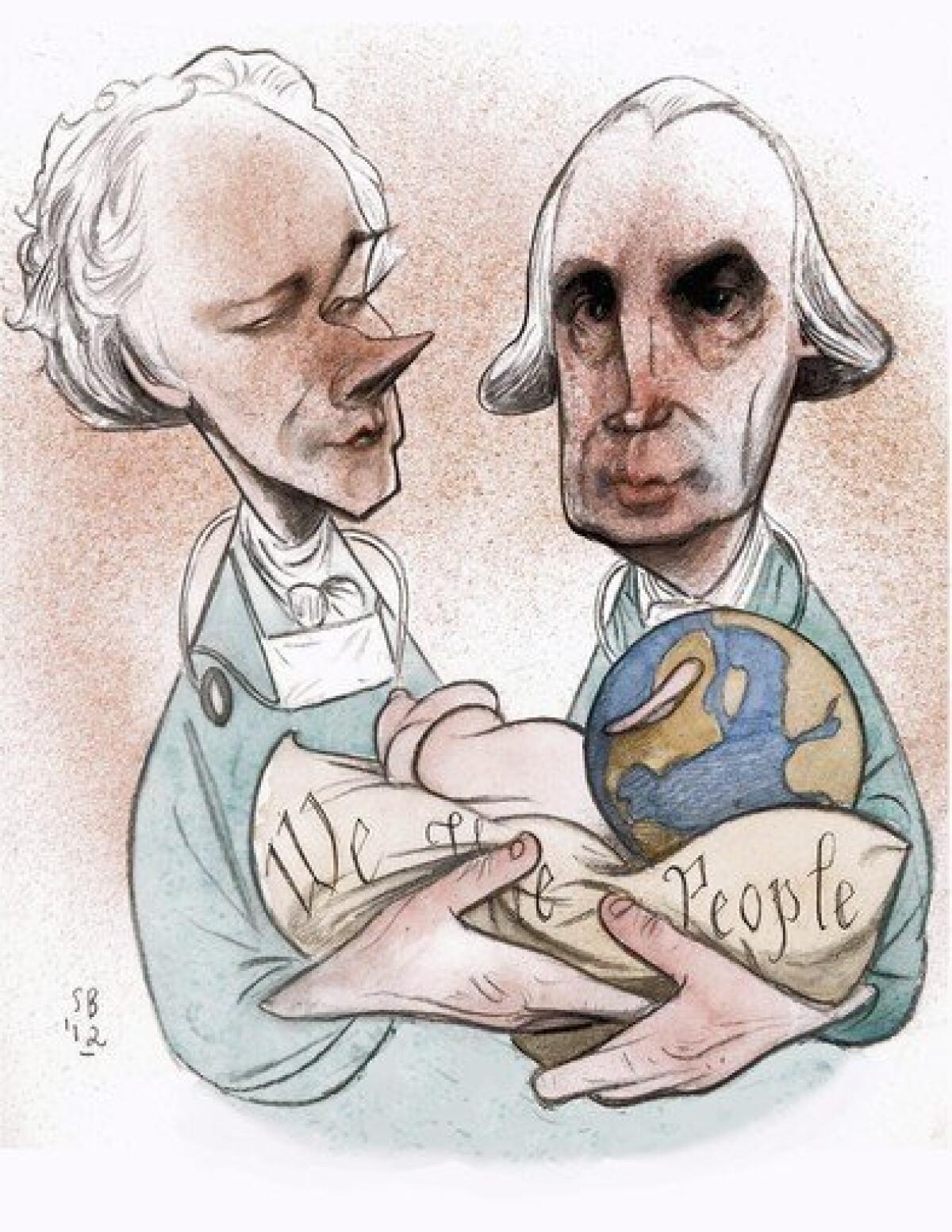

Here’s what. On Sept. 17, 1787, a small cluster of American notables who had been meeting behind closed doors in Philadelphia went public with an audacious proposal. The plan, signed by George Washington, Benjamin Franklin and 37 other leading statesmen, began as follows: “We the People of the United States … do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America.”

Of course, on Sept. 17, nothing had yet been ordained or established. The proposal was a mere piece of paper. But what happened over the ensuing year, in special elections held in every state, made the opening words flesh: We, the people of the United States, did in fact ordain and establish the Sept. 17 proposal.

This was big news on the world stage. Before the American Revolution, no regime in history — not ancient Athens, not republican Rome, not Florence nor the Swiss nor the Dutch nor the British — had ever successfully adopted a written constitution by special popular vote.

Nor did Americans do so in 1776. The Declaration of Independence was not put to a popular vote, nor were any of the state constitutions that were adopted that year. In 1780, the people of Massachusetts successfully launched a state constitution based on a special popular vote, and in 1784, New Hampshire followed suit. On Sept. 17, 1787, the proposed United States Constitution took this new idea to scale, inviting Americans across the nation to deliberate and vote on how they and their posterity should be governed.

In this unprecedented series of special elections, most states lowered or waived their ordinary property requirements. Never in human history had so many gotten to vote on society’s basic ground rules.

True, the ratification elections of 1787-88 look anemic when judged by the standards of 2012: What about women and slaves? But women and slaves had never voted anywhere in the world before 1787. Judged by the standards of its era, the breadth of democratic participation was epic — world-changing.

So was the depth of participation. In the ratification elections of 1787-88, the continent teemed with talk of the freest sort. Both supporters and opponents of the September plan spoke freely, with almost no fear of legal or political persecution. Leading men on both sides of the Great Debate of 1787-88 later came to hold positions of high honor — as presidents, vice presidents and Supreme Court justices — under the new regime.

The American conversation in 1776 had been far less open. The war had begun well before independence was declared, and virtually all who opposed independence in 1776 were cast into political exile. Almost none of these men later held any noteworthy American office, ever.

Shortly after the people convened in 1787-88 to say “Yes, we do,” Americans fashioned a Bill of Rights to fix some of the biggest bugs of Constitution 1.0. In effect, the document was crowd-sourced by the people themselves. Unsurprisingly, no phrase appeared more often in the Bill of Rights than “the people.” Later amendments carried forward this democratic momentum, repeatedly expanding but almost never limiting liberty and equality, and eventually welcoming blacks, women, young adults and unpropertied Americans as equal democratic participants.

In short, the extraordinary democratic momentum generated by the votes and voices of 1787-88 has continued to propel America forward over the ensuing decades and centuries.

And not just America. The world is now far more democratic than ever, thanks largely to the ideological, economic and military success of the United States, which has proved that democracy can work on a geographic and demographic scale never previously thought possible.

Why should we care about democracy’s spread? For starters, because no well-established democracy in the modern era has ever reverted to despotism. Modern mature democracies have not waged war against one another or experienced widespread famine.

This still-young modern world was, in effect, born in the U.S.A., and this miraculous birth began exactly 225 years ago. Happy birthday, America. Happy birthday, world.

Akhil Reed Amar teaches law and political science at Yale and is the author of “America’s Unwritten Constitution: The Precedents and Principles We Live By.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.