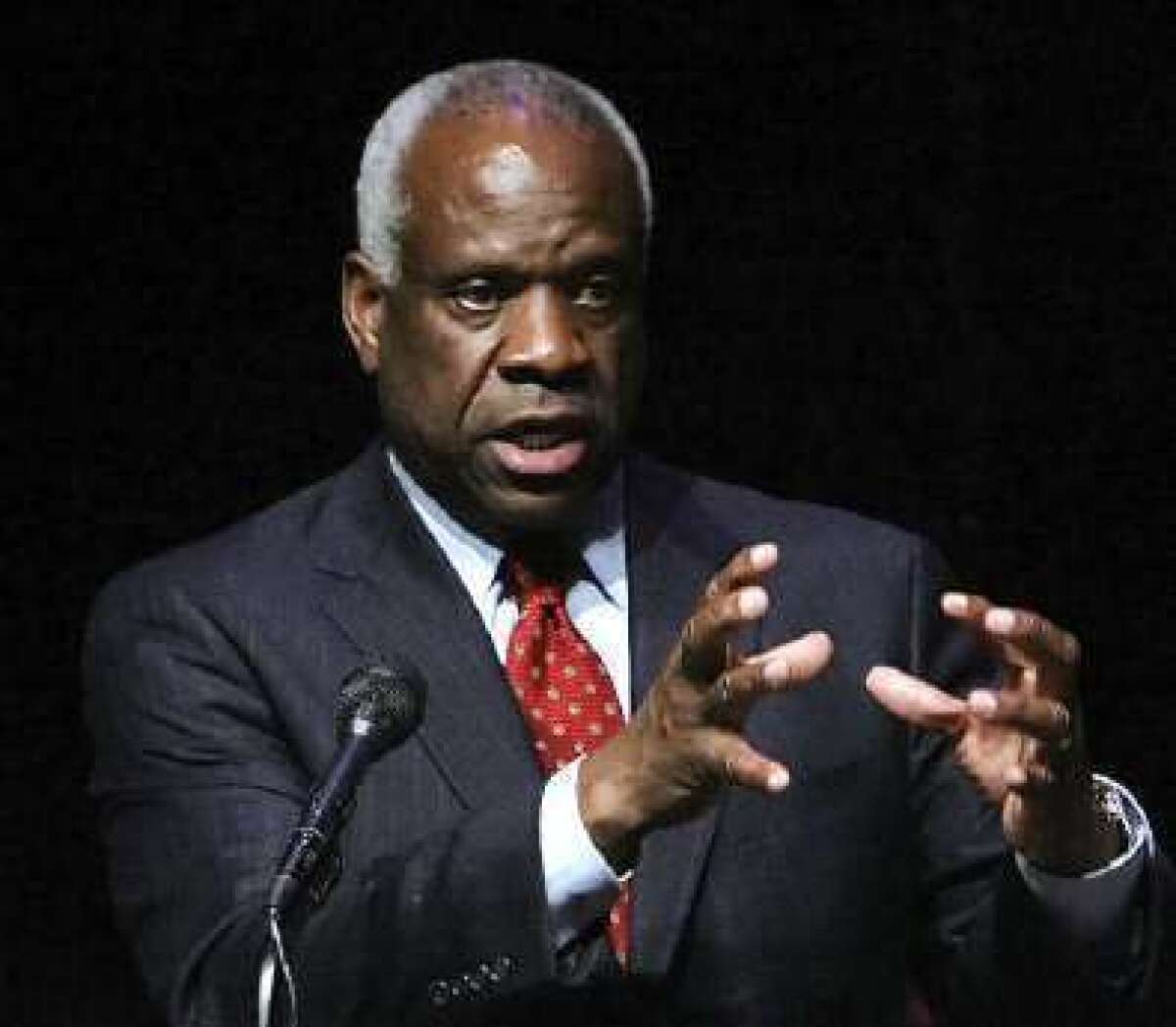

Clarence Thomas and the gospel of colorblindness

- Share via

One of the most annoying habits of some of my liberal friends is their casual derogation of Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas.

Thomas is derided not just as an extremist, which is true when you plot the legal philosophies of the justices along a spectrum, but also a clone of Antonin Scalia and an intellectual lightweight. The latter two accusations are just false. Thomas and Scalia have disagreed in significant cases, and Thomas’ opinions, however idiosyncratic, are often tightly reasoned and provocative.

That’s the case with Thomas’ opinion in the University of Texas affirmative action case decided this week.

Along with Scalia, Thomas signed Justice Anthony Kennedy’s majority opinion asking a lower court to take another look at whether the university’s policy of taking race into account satisfied the “demanding burden of strict scrutiny” articulated in a 2003 decision upholding racial preference sat the University of Michigan Law School (Scalia said he could sign the opinion because Abigail Fisher, the rejected white applicant who brought the suit, hadn’t asked the court to overrule the 2003 decision. True enough, but her lawyers would have been happy with that outcome, and the length of time it took for the court to hand down the recent ruling suggests that at some point several justices were flirting with overruling or gutting the earlier decision.)

Like Scalia, Thomas thinks the 2003 decision was wrong. In his opinion in the Texas case, he quotes his own opinion in a 1995 decision in which the court held that even benign racial classifications -- such as preferences in government contracts for minority contractors -- must be examined by courts with “strict scrutiny,” an exacting standard of review that often leads to invalidation.

Thomas wrote: “Purchased at the price of immeasurable human suffering, the equal protection principle reflects our nation’s understanding that [racial] classifications ultimately have a destructive impact on the individual and our society.”

This is what is sometimes called the “colorblind” interpretation of the 14th Amendment’s guarantee of “equal protection of the laws,” and it is subscribed to by other conservatives on the court, including Chief Justice John. G. Roberts Jr.

Appropriating the conservative insistence on interpreting the Constitution according to the intent of the framers, critics of the colorblind approach note that the members of Congress who supported the 14th Amendment also backed race-conscious programs to help former slaves.

But it is true that in the heyday of the civil rights movement, in court and in political discourse, colorblindness was gospel. Thomas quotes from a lawyer for the black children who challenged segregated schools in the Brown vs. Board of Education case: “[N]o state has any authority under the Equal-Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment to use race as a factor in affording educational opportunities among its citizens.”

Thomas’ opinion is worth reading for its eloquent enunciation of the colorblind principle, and also for his related argument that courts shouldn’t budge from that principle because of the claimed advantages of race-conscious policies. (In the affirmative action context, those advantages include the “educational benefits of diversity.”)

Thomas noted that segregationists “asserted that segregation was not only benign, but good for black students. They argued, for example, that separate schools protected black children from racist white students and teachers.”

In a brutal comparison, Thomas likens this paternalism to the motives of the University of Texas: “The university’s professed good intentions cannot excuse its outright racial discrimination any more than such intentions justified the now denounced arguments of slaveholders and segregationists.”

You can find historical fault with the colorblind approach, and I happen to believe that there is a moral difference between race-conscious policies designed to bring people together and those designed to keep people apart. (Promoting integration seems to me a sounder rationale for affirmative action than the very debatable “educational benefits of diversity.”) But the colorblind interpretation has a stark moral simplicity about it that appealed even to Martin Luther King Jr. King, by the way, makes an appearance in Thomas’ opinion.

“It is irrelevant under the 14thh Amendment,” he wrote, “whether segregated or mixed schools produce better leaders. Indeed, no court today would accept the suggestion that segregation is permissible because historically black colleges produced Booker T. Washington, Thurgood Marshall, Martin Luther King Jr. and other prominent leaders. Likewise, the university’s racial discrimination cannot be justified on the ground that it will produce better leaders.”

ALSO:

Why such hysteria over fracking?

Did Obama diss Catholic schools in Belfast?

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.