Op-Ed: Patt Morrison asks: California earthquake expert Lucy Jones

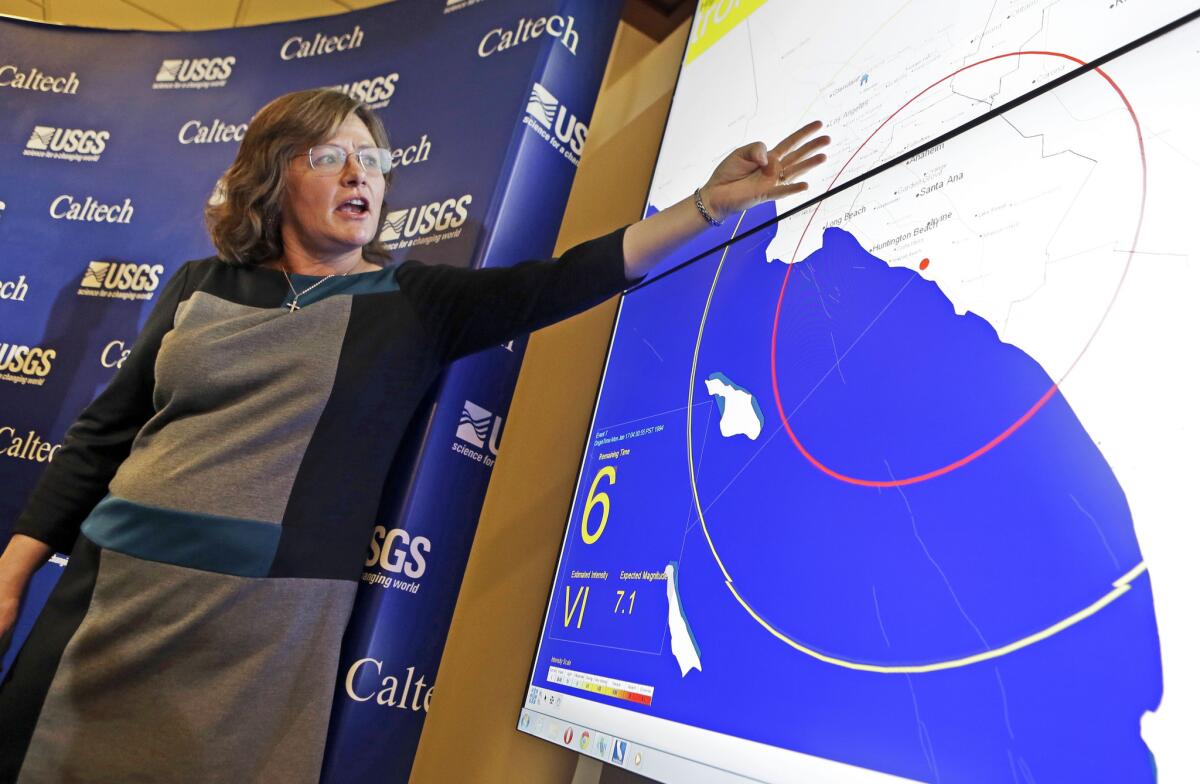

Seismologist Dr. Lucy Jones said in a Twitter posting that she’s leaving federal service but will remain at the California Institute of Technology.

- Share via

A young Winston Churchill once wrote that “Nothing in life is so exhilarating as to be shot at without result.” In Southern California, we can feel the same way when the ground starts to quake and we ride the earth like buckaroos until the shaking is over. The renowned U.S. Geological Survey seismologist Lucy Jones has studied our earthquakes, and gone on television time and again to give us information and comfort. Now the “Earthquake Lady” is retiring – but s till kind of wishing, in the nicest possible way, for a chance to experience a Big One.

CLICK HERE TO LISTEN TO THIS INTERVIEW ON THE ‘PATT MORRISON ASKS’ PODCAST>>

First, I’m going to use the phrase “the big one” in a different context. I want to ask you about another “big one,” which is the big lesson of what your years of science and research have taught you about human nature.

I think one of the more interesting things I’ve done in the last decade is really get more informed about what social science tells us about how people feel about disasters. Psychologists have shown that people don’t make rational decisions about the risks they face. Even in Southern California, we have killed more Southern Californians with landslides and floods than we have with earthquakes. But who’s afraid of the rain?

I always try to remind people that the week of the Northridge earthquake [in 1994], more people died in an ice storm on the East Coast than in the earthquake. Earthquakes are not a big threat to our lives. They are a threat to our pocketbooks, and they’re a threat to the viability of the economy of Southern California. But you’re far more likely to die on the freeway. In fact you’re far more likely to be murdered than you are to die in an earthquake.

And they’ve actually been able to show what are the things that make us afraid: it’s unpredictability, unseen, not-understood dreadedness of the outcome. The one other thing that pushes everybody’s buttons is intentionality. So when you look at how we respond to the terrorist threat, it’s nothing about the actual physical risk to your life. It is about the psychological damage that somebody’s out to get us – and out to get us because of who we are. Earthquakes trigger all these buttons, and so we’re afraid.

So when I give the earthquake a name and I give it a number and I give it a fault, we’re saying, somebody understands what’s going on here and that’s reassuring.

I remember when I first heard people say, Oh, it’s so important to see you, it’s so comforting after the earthquake. And I’m going, what? I’m telling you there’s going to be aftershocks, and that’s comforting? And yet it is because it’s saying there’s order to it. And I think on a fundamental level, we feel better when mommy tells us it’s okay than when daddy does.

People still ask, What does it measure on the Richter scale? Poor Charles Richter: the phrase is entrenched but seismologists don’t find it very useful any more.

Charlie Richter took it from the magnitude of stars. He’d been trained as an astrophysicist. He was trying to help people understand that what happened in the earthquake was not just what you feel.

But what’s happened now is people don’t know how to talk about what they feel. I can’t tell you how many people have said, Okay so it was a magnate 6.7 in Northridge, but what was it at my house?

I’d like to see us, if I could wave a magic wand and change how we talk about earthquakes, get rid of magnitudes. It’s just a completely arbitrary scale that really doesn’t mean anything. And since that time, we have come up with a way of measuring the earthquake. We call it the seismic moment. We actually proposed that we could create a unit called the Aki. Keiiti Aki was a professor, first at MIT then at USC, who created the concept of seismic moment.

So we could have an Aki and a kilo-Aki and a mega-Aki and a micro-Aki. Because the range of earthquakes, from the smallest you can feel to the biggest we have in the world, is about 15 orders of magnitude, and we try to describe that between a magnitude 2 to a magnitude 9.

You know, actually: This is a micro-Aki, this is an Aki, this is a mega-Aki – that gives people a better feeling of how big the difference is. And then we can reserve the simple numbers, one two three four five six seven eight nine, for the intensity.

I think it would remove a lot of the misinterpretation, but it’s a very big change. And most of my colleagues go, But people know magnitude! And I’m like, Yeah, but I don’t think they understand it.

In the movie “L.A. Story,” there was a scene most Angelenos cherish, where a group of people is sitting at brunch, an earthquake hits, and Steve Martin guesses at the magnitude – with great aplomb, I have to say.

The best way to guess the magnitude is to count how long it lasts, because as you get to the bigger earthquakes, they last for a longer time. I can remember the Landers earthquake – Landers is ’92, two years before the Northridge earthquake – 7.3 was the final magnitude. I was lying in bed and I started counting. I counted up to 30 seconds before I got out of bed. So I knew it was bigger than magnitude 7 before I even got out of bed.

How has technology changed your job, both the communications aspect and the science?

Oh, it’s changed it fundamentally. And the field has changed completely because of it. When I first started, I spent months pulling out magnetic tapes downloading seismograms, reading the records to locate earthquakes. Doing that same paper that took me six months of work – now, that part of the work would happen in a day.

Actually, I have found Twitter wonderful because I can go and respond on Twitter and just give the magnitude, say where I expect for aftershocks, say what fault it is, and I’m in control of exactly how it’s phrased. I have to get it down to 140 characters, but I’m sure I’m not going to be misquoted then.

This is kind of a ghoulish question, I suppose, but is there one earthquake in California you wish you could be around to witness if you had the opportunity?

Oh, I want to see the San Andreas earthquake. I mean, I don’t want to do it to people, but given that it has to happen, I really hope I’m still alive when it comes along, because we’re going to learn a lot about it.

They still do have earthquakes in the east. You get a three-point-something in New York, and it would be blazing headlines.

Earthquakes in the east get felt over a larger area. An earthquake happens on a fault, and that puts off energy just like snapping your fingers: you slip across your fingers and you create a soundwave. You slip across a fault, and you create a soundwave that travels through the earth.

How it travels depends on what the earth is like. Here in California, our rocks are young and relatively hot and broken up with lots and lots of faults. So just like a cracked bell, it’s not a very good transmitter of energy and you don’t have to get very far away from the fault and have the shaking be a lot less.

On the east coast, rocks are older and colder and harder and less faults, so when the energy gets put into the crust there, it tends to transmit it very easily. We see relatively small earthquakes felt over a much larger area.

The Washington Monument got damaged.

At 80 miles away from a 5.8. Eighty miles away from a 5.8 in California, you might not feel it.

Is there a really good earthquake joke or cartoon – a cartoon you’ve got on the fridge or on the door of your office?

I don’t have any cartoons. Most of them seem to be the same joke I’ve heard 500 times: it’s not my fault, and that sort of thing. But I did keep a sign for quite a while that I saw at my stepmother’s office.

My stepmother is a biologist at Santa Monica College, and her office was destroyed in Northridge [earthquake] and they had to relocate and rebuild the building. And somebody had put up the sign that “Earthquakes are the way the earth relieves stress by transferring it to those who live on it.” That one I kept around.

Of course earthquakes are great fodder for movies, and there are some that do a good job and some that don’t.

More that don’t! I go, why are you trying to learn your science from a Hollywood movie? Do not take this seriously!

Now, there are some [filmmakers] that have worked with us and tried to get it accurate. Sometimes it’s very frustrating to me because I think we could make a great movie while being completely legitimate in the science.

The one movie that I thought got it the best, that you’ve got to go back in time to, is the 1974 “Earthquake” movie with Charlton Heston. The whole damage part was what those disaster movies do, but the beginning of the movie – with the scientists getting worried and going and talking to the mayor – it wasn’t that they were saying, I know an earthquake’s gonna happen. They were saying, Something’s happening and I don’t know what it means. That was the realistic one.

You know, it’s a funny thing, and I think it’s connected to how little we educate people about earthquakes. If you look at the California state curriculum, the only mention of earthquakes is that in sixth grade, you learn that they result from plate tectonics.

I think that our citizens need to know more than that to live with them. And I think the impoverishment of our movies is a reflection of an impoverishment of education.

You spent time in the mayor’s office and you saw some of what you alluded to – the scientists and the engineers – and you saw the other side of that triangle, which is the politics and the lobbying and the economic forces that are at work.

A large part of what I did in the mayor’s office was getting out and talking with groups, talking with the engineers, talking with building owners, talking with the LA Conservancy, talking with business owners, and saying, This isn’t about whether or not you have to spend a certain amount of money on a building. This is about whether we will have a functioning economy after the earthquake.

And when you put it in that context, and help take them through, treat them as adults, give them the full info, we didn’t end up with opposition.

The building owners and management associations stood up with the mayor and said, Yes, this is going to cost us $5 billion, it’s what LA needs.

When you drive around and look at things, and you see things we don’t, what shape things are in –

Aha, the magic eyes of the geologist!

The magic eyes of the geologist. Do you get to switch them off, or are they always on?

They’re always on, unfortunately.

I remember being in El Paso, all those unreinforced masonry buildings, and I was like, Oooh, they don’t’ have earthquakes, gotta remember they don’t have earthquakes. And then they had a magnitude 5 two weeks after I was there! It was far enough out of town that it didn’t actually bring down those buildings.

The places you can go that don’t have earthquakes tend to have hurricanes or really bad snowstorms. I’ll take the earthquakes.

You’ll be retiring from this job but still working, still keeping your hand in.

I have spent 33 years as a government employee, a federal research scientist, and it’s time to have space for younger ones.

And I’ve reached the point in my career that what really interests me now is implementing this work. I’m going to start by writing a book, that’s the first thing. And I hope to be spending time working with policy people, with my fellow scientists, about how to communicate but really focus on the science communication, because I think as we further disrupt the earth’s climate, our population has to understand the science or we’re going to destroy the world.

And you’re going to work on your music, too.

When I was in college, I took Chinese, physics and Renaissance music. I wondered at one point whether I was going to go into the Foreign Service, become a research scientist, or become a classical musician. I finally decided that being a professional scientist and an amateur musician was a better-paying option than a professional musician and an amateur scientist. And I was a better scientist than I am a musician. But in my adult years, and with the children now out of the house, and more time, I’ve gone back to playing the viola da gamba. And it’s very soothing to the soul.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.