Op-Ed: Before Bernie Sanders, there was Upton Sinclair

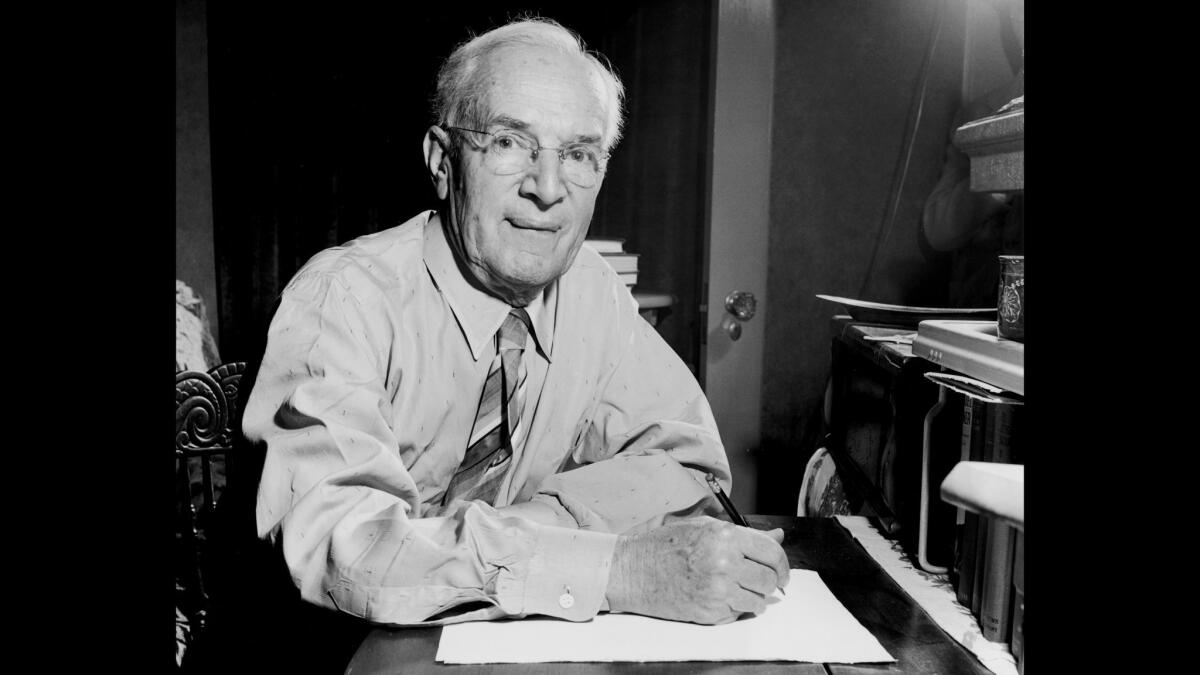

American author Upton Sinclair, writing by the light of his desk at home in California in 1948.

- Share via

Although Donald Trump’s presidential campaign has understandably garnered more headlines, the campaign of Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders is truly the one worth parsing. Americans have welcomed racist demagogues before, but an avowed socialist? The most successful presidential campaign by a democratic socialist was that of Sanders’s hero, Eugene V. Debs, in 1912. Debs won 6% of the vote. In the most recent CBS/New York Times poll, Sanders was pulling down 41% support from Democrats, and other polls show him running even or ahead in Iowa and New Hampshire.

On the national stage, the Sanders phenomenon seems new; the closest antecedent is the campaign that socialist author Upton Sinclair waged for governor of California in 1934. In the depths of the Depression, just one year after Franklin Roosevelt became president, Sinclair switched his party registration from Socialist to Democrat, a change unaccompanied, however, by shifts in his beliefs or ideology.

In his short campaign book “I, Governor of California, and How I Ended Poverty,” Sinclair laid out his plans to put the unemployed to work on a host of public projects. The manifesto spawned hundreds of End Poverty in California (EPIC) clubs. Six centrist Democrats and Sinclair all entered the Democratic primary for governor; to general astonishment, Sinclair won handily with just over 50% of the vote.

Until one month before the general election, Sinclair was widely believed to be leading the unpopular Republican incumbent, Gov. Frank Merriam, but a breath-taking campaign of falsifications by the state’s leading newspapers and movie studios helped give Merriam a come-from-behind victory. (MGM produced films depicting dangerous-looking characters, played by actors and extras, saying they were coming to California if Sinclair was elected; these films were then screened as “newsreels” in every movie theater in the state.)

Sinclair’s influence on California politics didn’t end with his defeat. On the contrary, his campaign revitalized what had been a moribund Democratic Party. Among the thousands of activists who’d flocked to his banner were a new crop of liberals who won election to the state legislature, among them Augustus Hawkins, the African American representative from South Los Angeles who carried much of the state’s landmark civil rights legislation while he served in the Assembly. Later he was elected to the U.S. Congress, where he authored important full employment legislation. Another Sinclairite, Jerry Voorhis, was a leading progressive U.S. Congressman for a decade until losing his seat in 1946 to a red-baiting campaign from Richard Nixon.

Like young people in the 1930s, today millennials have paid a steep price for unregulated capitalism’s failures.

EPIC, said Stanley Mosk, a Sinclair supporter who went on to become California’s attorney general and a justice on the state’s Supreme Court, was “the acorn from which evolved the tree of whatever liberalism we have in California.”

It’s not a stretch to suggest that the current campaign of Bernie Sanders will have an analogous effect on the nation’s Democratic Party and its liberal movement.

His critique of Wall Street has resonated deeply and widely within and beyond Democratic ranks, clearly prompting Hillary Clinton to embrace reforms she hadn’t espoused previously – such as cracking down on shadow banks, vowing to jail miscreant bankers. With polls showing Sanders leading Clinton among young voters, his campaign is creating a distinct cohort in American politics, much as the anti-Vietnam War presidential campaigns of Eugene McCarthy, Robert Kennedy and George McGovern activated a generation whose perspectives later came to dominate Democratic politics.

Indeed, Sanders is mobilizing a generation already moving left—and in this, too, he resembles Sinclair. Like young people in the 1930s, today millennials have paid a steep price for unregulated capitalism’s failures. The year Sinclair ran for governor, San Francisco and Minneapolis were swept by general strikes; once quiescent unions were hiring young organizers by the carload. Sanders announced his candidacy in the wake of Occupy Wall Street, the Dreamer movement, Black Lives Matter, and the fight for a $15 minimum wage. Polling has shown Americans under 30 view socialism more favorably than capitalism.

In the improbable (but not impossible) event that Sanders wins the Democratic presidential nomination, he will certainly be subjected to a latter-day version of the calumnies heaped on Sinclair – but like Sinclair, his influence will surely outlive his campaign. He’s prodding a party and a generation to define their missions as reversing America’s descent into plutocracy.

Harold Meyerson is executive editor of the American Prospect.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.