Op-Ed: How a San Francisco beach bonfire set the world aflame

- Share via

When Larry Harvey, who died Saturday at age 70, first burned a stick effigy of a man on Baker Beach in San Francisco in 1986, he was impressed that a small public act would capture the attention of strangers. It inspired a woman to walk up and touch the torched figure; it inspired another onlooker to compose a song on the spot. It had unexpected, unifying meaning.

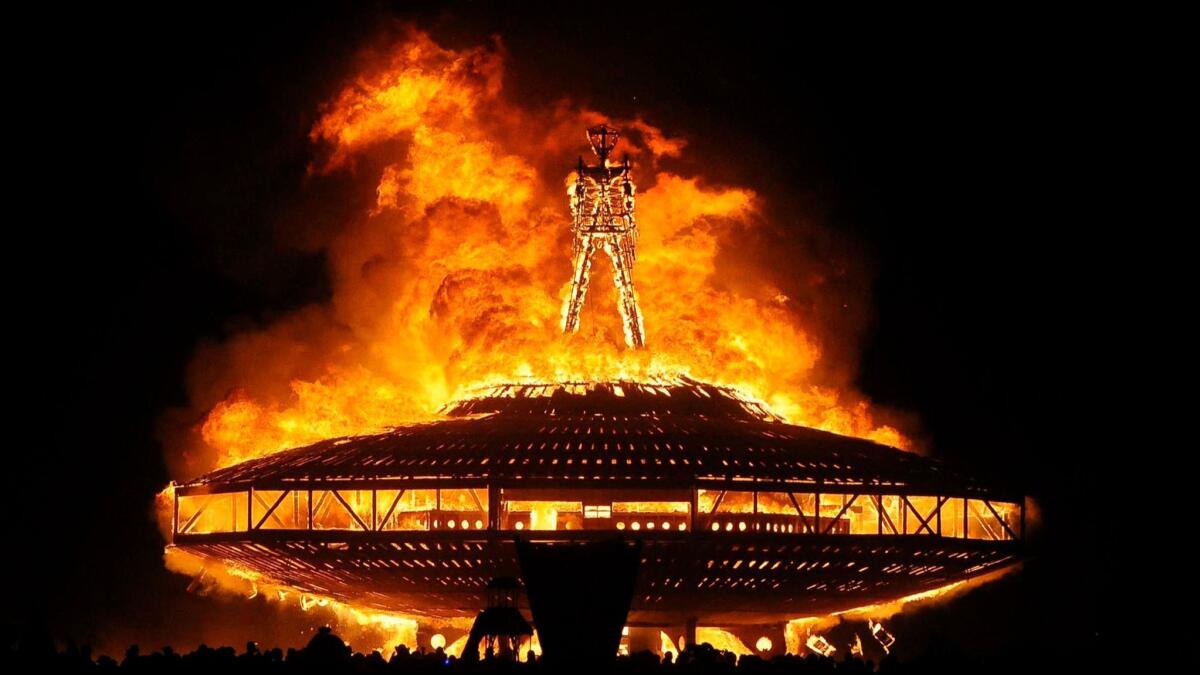

Harvey made that act into a yearly ritual, a response to his own yearning for the unexpected and the unifying, and it came to be called Burning Man. The crowds that wanted to interact with the burning of an effigy increased over three decades to more than 70,000. That small bonfire morphed, without planning and without any single obvious reason, into one of California’s most significant contributions to American and world culture.

By 1990, Harvey’s Burning Man ritual had outgrown San Francisco and relocated to Nevada’s capacious Black Rock Desert, where it still unfolds, over a week of collective creation, at summer’s end. The tickets quickly sell out, even though the price of admittance (most tickets are $425), requires you to drag yourself to a faraway, desolate space, prone to brutal heat and destructive dust-storm winds, with no services provided besides porta-johns, where the collective you is essentially responsible for your own entertainment.

Burning Man melds aspects of two characteristically Californian institutions: the theme park and the cult, with a unique take on both.

The gathering is an elaborate and magical Disneyland whose attractions are interactive art and performances created by the paying customers, a spectacular explosion of “maker culture.” As for its cultlike properties, Harvey was sometimes painted as a quasi-guru to a flock of “Burners,” and he did believe Burning Man should and would change the larger culture around it.

Burning Man creates cultural effects the way mountains create weather.

But Harvey intelligently steered Burning Man’s “meaning” with a light hand. In later years, he promulgated a set of “10 principles” that suggested how best to contribute to the communal creation of a fully functioning Black Rock city, dedicated to art, that also disappeared itself in a week: Radical self-expression. No commerce. Absolute self-reliance. Immediacy. Participation. He wasn’t delivering commandments as much as reflecting back the ideas that Burning Man cultivated.

One of Harvey’s key principles was inclusion: Try not to make anyone feel unwelcome. As Burning Man caught on, its aficionados had to decide whether to zealously preserve it as they first experienced it, or bow to that welcoming spirit, embracing more and more adherents of every background, opening it to influences beyond its original Bay Area bohemian roots. Harvey decided locking down the experience would betray its truest essence.

As the ‘90s progressed Burning Man evolved alongside, and became a key barometer of cool in, the digital business culture of the Bay Area. Google’s founders used the Burning Man icon as the very first Google doodle; Elon Musk once said no one can understand Silicon Valley if they haven’t been to Burning Man.

Burning Man also captured a wide range of Los Angeles creatives — the “Burning Man episode” has become a near-cliché in TV sitcoms (“The Simpsons,” “Malcolm in the Middle,” “Crazy Ex-Girlfriend”). The look of Burning Man, its setting and finery, are advertising and fashion industry mainstays.

“Transformational festivals” openly aligned with or clearly inspired by Burning Man now happen in Texas, Florida, Missouri and many other places across the United States and the world. The month before Harvey died, Burning Man’s unique style of public interactive sculptural art — often relying heavily on light, fire and motion — was honored with an exhibition at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington.

Participating in Harvey’s ritual has become a key marker of identity for tens of thousands of participants. Burning Man creates cultural effects the way mountains create weather. That didn’t happen because of commandments or a guru’s charisma: It grew from the experience itself.

Harvey saw Burning Man, he once told me, as a solution to “the quiet desperation Thoreau wrote of,” a space where people could discover “what they were meant to do with the transcendent faith that they were meant to do that something,” free of “judgments governed by the world’s standards.” The event Harvey launched injected a fresh ritual into American life, with new standards of fellowship and communal real-time culture-making. As he recognized, we needed it. We still do.

Brian Doherty is a senior editor at Reason magazine and author of the book “This Is Burning Man.”

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.