Op-Ed: How to make the Senate consider Merrick Garland for the Supreme Court

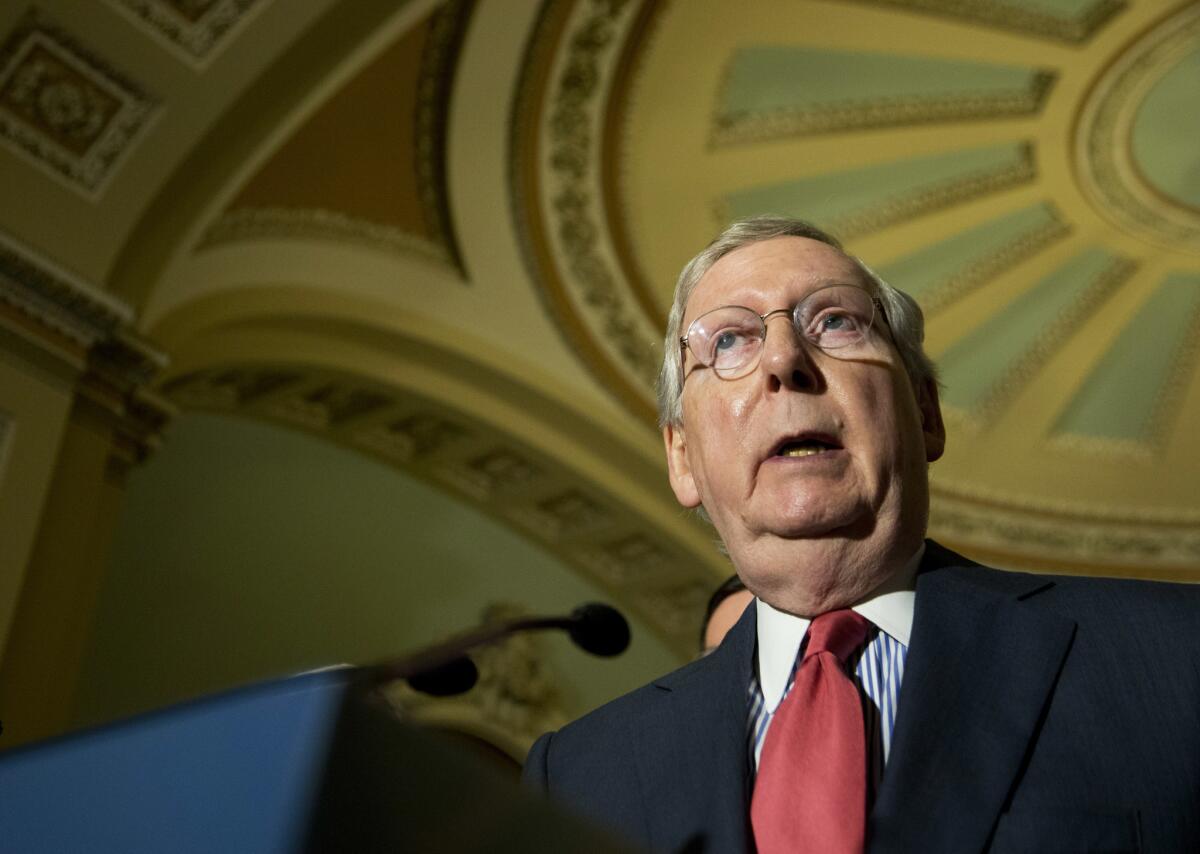

Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell of Ky. speaks to reporters on Capitol Hill on April 19.

- Share via

Nearly two months after President Obama tapped Judge Merrick Garland to fill the vacancy on the U.S. Supreme Court, the Senate has failed to schedule so much as a hearing on his nomination.

The Senate taking a long time to get something done is hardly noteworthy. What is shocking, however, is how boldly and unapologetically Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) and other Republican lawmakers have declared their intention to put politics before the functioning of the Supreme Court.

Senators and representatives of both parties have lauded Garland as a dedicated public servant, an outstanding legal mind and a worthy nominee. Neither McConnell, Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa), nor any other Republican lawmaker has flagged as disqualifying any element of Garland’s 19-year record on the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals.

The anti-Garland blockade has exposed the lengths to which Republican leaders will go to avoid holding politically inconvenient votes, abdicating their basic responsibility.

In fact, they have stated that the only reason they will not consider his nomination is that a presidential election is underway. The day Garland was nominated, Grassley issued a statement declaring that he and a majority of his Senate colleagues would be “withholding support for the nomination during a presidential election year, with millions of votes having been cast in highly charged contests.” Garland’s name didn’t appear anywhere in the four-paragraph statement.

As a result of these senators’ nakedly political decision, some of the more important legal questions of our generation — questions, for example, affecting access to reproductive healthcare and determining the fate of immigrant families protected under the president’s executive actions — will go unresolved.

Already the court is signaling that it will postpone hearing some controversial cases until at least 2017. And for many cases heard this year, legal experts expect 4-4 rulings. These will create legal uncertainty, as deadlocked Supreme Court decisions leave in place the often conflicting rulings of the Circuit Courts. In fact, in many instances, the Supreme Court agrees to hear cases precisely to resolve such conflicts.

The impact of the Senate’s inaction goes beyond hobbling the Supreme Court. The anti-Garland blockade has exposed the lengths to which Republican leaders will go to avoid holding politically inconvenient votes, abdicating their basic responsibility.

Congress has yet to send President Obama meaningful legislation to address the water crisis in Flint, Mich., the debt crisis in Puerto Rico, or the threat posed by the Zika virus — let alone measures to reform our immigration system, prevent gun violence or fix a broken campaign finance system that has angered Americans on both sides of the aisle and across the country.

When did it become predictable, much less acceptable, for Congress to stop doing its job during election years? How can we expect Congress to act on complex issues when the election season seems to lengthen every cycle? If the Senate follows through on its plan to ignore Garland’s nomination, it would set a new and appalling precedent for inaction.

Frustrated by the status quo, a group of six of us — the two authors of this piece along with Reps. Patrick Murphy (D-Fla.), Ann Kirkpatrick (D-Ariz.), Tammy Duckworth (D-Ill.), and Jared Polis (D-Colo.) — are introducing legislation to provide Congress with an incentive to get to work.Under our proposal, titled “Senate’s Court Obligations Trump

Unconstitutional Stalling,” or “SCOTUS” Act, if the Senate does not take action on Garland’s nomination within 125 days of the date he was nominated, neither chamber will be permitted to adjourn. Instead of leaving town to participate in the July party conventions and campaign this fall, the Senate must remain in Washington to fulfill its constitutional responsibility. Never in history has it taken longer than 125 days for any Supreme Court nominee (who has not withdrawn from consideration) to receive a Senate hearing, so we believe this timetable is more than reasonable.

We recognize that McConnell and his colleagues in leadership are highly unlikely to take up our measure, which would require them to do a job they have spent the last two months adamantly refusing to do. What the SCOTUS Act offers is the opportunity for members of both parties to go on the record about what they believe is more important: A totally imaginary right of a new president to fill Supreme Court seats vacated late in the last president’s term, or fulfilling our duty as legislators.

To our House colleagues who might question why they should have to wait around D.C. for the Senate to do its job, we simply respond that the House also has a long list of unaddressed problems that need solving. We should have no trouble finding a productive use of the time. When congressional leaders decide they don’t have to do their job during an election year, there should be consequences.

Elizabeth Esty is the U.S. representative for Connecticut’s Fifth Congressional District. Chris Van Hollen is the U.S. representative for Maryland’s Eighth Congressional District.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.