Op-Ed: A surprise among the boxes Dad left behind

- Share via

Forty years ago, when I was fresh out of college and not sure what to do with myself, my father gave me some advice. I had job applications out to what seemed like every newspaper in Southern California. Waiting tables, atrociously, in a Mexican restaurant was not my dream job. I was temporarily living in my dad’s condo. I needed a mission beyond slinging the No. 4 combo and margaritas. I can still hear his words today, challenging and sympathetic.

“Go do something. Even if it’s wrong.”

It was a concept much in keeping with Dad’s general “never complain, never explain” worldview.

I took his advice. That day I collected my waiter’s tips from a dresser drawer, bought a round-trip ticket to Frankfurt, Germany, then packed my bags and hit the road. I ran out on my job, girlfriend and student debts. It felt wrong but good.

With something like $420 in my pocket, I had decided on a mission: See Europe and, for sure, No. 7 Eccles St. in Dublin, Leopold Bloom’s home in “Ulysses.” (I was an English major.) And, always drawn to the impossible, I wanted to walk Loch Ness in search of the monster. Among the many snapshots I have of that summer, one is of myself standing in the crumbled doorway of No. 7 Eccles St. and another is of Loch Ness, smooth and shiny and utterly monster-less.

Do something. Even if it’s wrong.

Well, maybe not fully wrong. But I did something that I wouldn’t have done without Dad’s provocative advice. And that was his bigger point, of course, to do. (And, perhaps, get out of my condo!)

I’ve tried to follow that advice, within reason, for better or worse, for my entire adult life. I’ve made some spectacular mistakes but enjoyed some surprising accomplishments.

Few of us really get much done by playing it safe.

**********

Dad died in 2009. He was 78. Not long ago I was going through the last of his things, stored in an outbuilding on my property. I’d been putting off the task for half a decade. Sometimes, keeping such things around is a comforting reminder of a life. At other times those same things are an unhappy reminder of death. It depends on your mood.

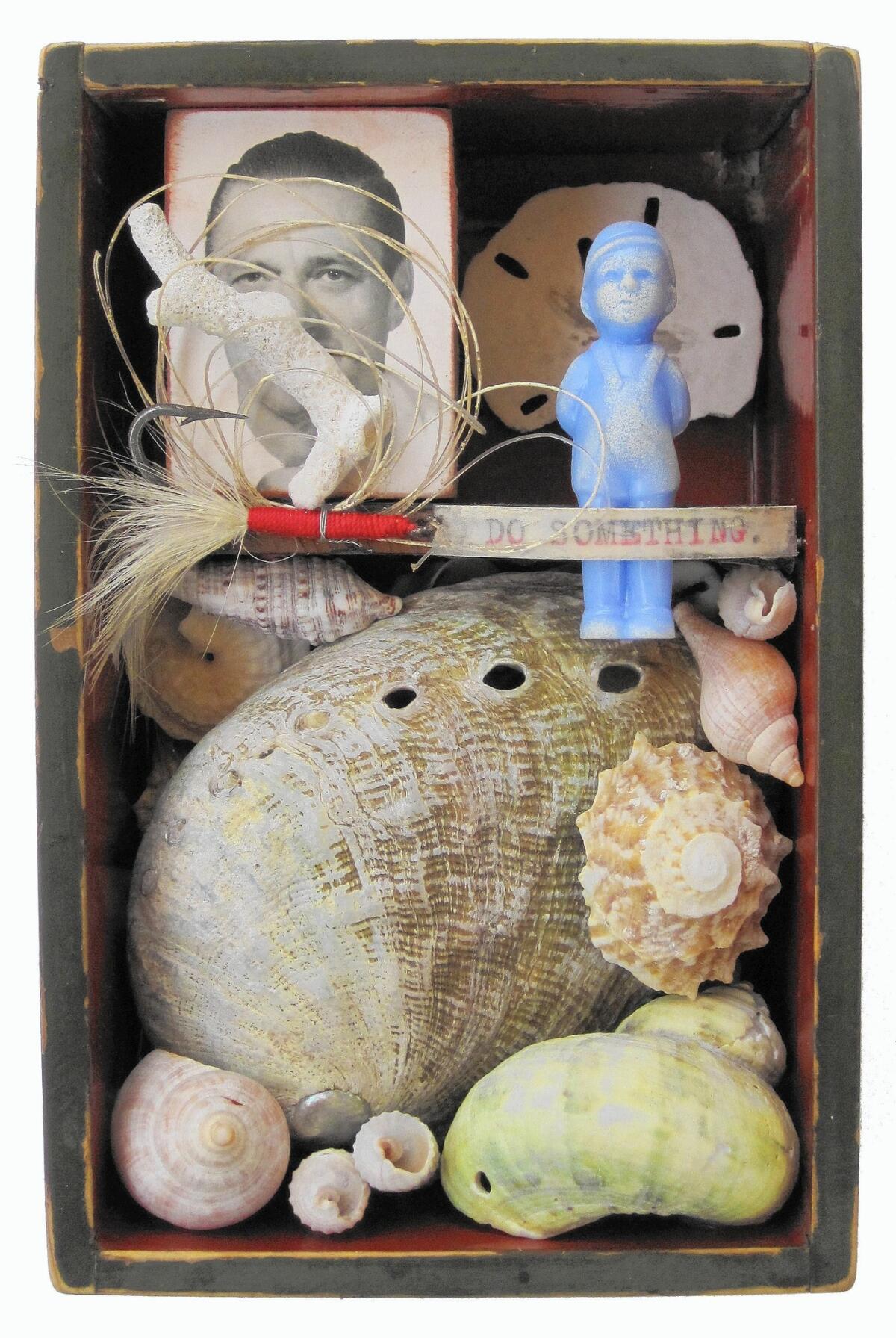

So I came down to the last few boxes. Each was clearly labeled in my father’s bold draftsman’s hand and neatly bound with good packing tape. What they held was representative but nothing you would call important: fly-fishing oddments, knives and knife sharpeners, a pair of very old Motorola walkie-talkies — large and heavy and stickered with faded red u-print labels: “RF Parker.”

The last box was heavy. It was labeled “Shells,” undoubtedly more of the empty shotgun shells and 30-06 brass that Dad had collected and reloaded. I’d already disposed of half a dozen such boxes of ammunition casings. Fifty years ago my dad had very patiently taught me to hunt and shoot, but I’d never learned to reload.

I set the box on a workbench. With a shop rag I swept the dust off its top, cut the packing tape and folded it open. Inside was a cache of seashells. Some I remembered from my boyhood, collected in Baja near San Felipe on camping trips; others probably came from Huntington or Newport.

I saw clams and small abalone and scallops and wavy turbans and sand dollars and smoothed-off coral that Mom used to put in bowls to decorate our Tustin home. The shells were mostly worn and chipped, as shells collected from beaches and stored for decades tend to be.

There was even a bag of store-bought seashells, some dyed in splendidly improbable colors, vibrant in their still-unopened plastic container. I wondered briefly why no one had never opened that bag, and I decided it was because store-bought-and-dyed could never match sought-after-and-found. I’ll never know. When your last parent dies, the list of things you cannot ask gets long indeed.

I grabbed a few trophies, closed up the box and pulled a fresh strap of packing tape across the top. I set it on a shelf, label showing. Over the years, I had had no problem discarding the 12-gauge shells and .45-caliber shells, but the seashells would remain in the family until at least the end of my generation.

Why? Because I loved the idea that Dad could still surprise me. That I’d jumped to the wrong conclusion about his box and what he valued. That I’d known him well but not fully.

**********

All of which set the stage for the entrance of my son, 16, bound for his senior year of high school.

“Hey Tom.”

“ ‘S’up?”

“Going through some of Grandpa’s things.”

“More shells?”

“Seashells this time.”

“Cool. Did you find a guitar cord out here?”

“It’s on the table.”

That outbuilding is where the band practices. Tom’s a bright, good-natured boy whom we realized, shortly after his birth, has a head shaped exactly like his grandfather’s (and mine). I have a snapshot on the wall of my dad holding baby Tom up next to him, cheek-to-cheek, the backs of their true-to-scale Parker heads to the camera (best angle).

At times like this, a father gets to thinking of his position on the great relay. What advice of mine, if any, might stick and help nudge my son through his years? Which one of my own boxes will hold the surprise that Tom will not see coming until he opens it? What of me will he choose to part with, and what will he keep?

On this Father’s Day, I propose that all you dads and sons, mothers and daughters put aside something unusual — something you but not you — for your next in line to discover, and maybe even be astonished by, later.

T. Jefferson Parker lives in northern San Diego County. His latest novel is “Full Measure.”

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.