Op-Ed: James Buchanan is proof there’s no ideal presidential resume

- Share via

In each presidential race, including the one we’re still slogging through, candidates tout their professional background as offering the best preparation for the job. Is leading a business like leading a country? Should one have foreign policy or military experience? At least a modicum of public service seems like a requirement.

But what if a lengthy career in public office, including elected and appointed posts, has little or nothing to do with a president’s job performance? What if it’s even a detriment? Having just steeped myself in the life of James Buchanan, I am quite skeptical that a long ride in government jobs automatically prepares anyone to lead an unwieldy nation like ours.

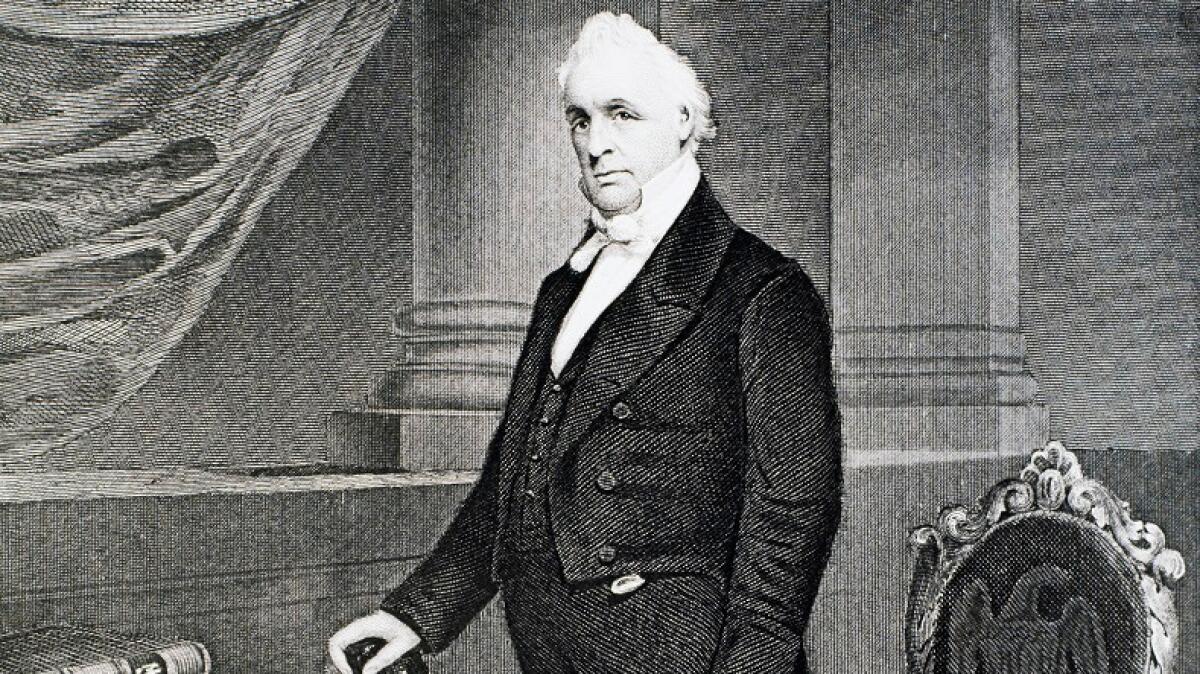

Buchanan was, easily, the most governmentally experienced presidential candidate in the first 80 years of the republic.

Buchanan was, easily, the most governmentally experienced presidential candidate in the first 80 years of the republic — and perhaps even through the present day. He was a state legislator in Pennsylvania, a member of the U.S. House, a U.S. senator, minister to Russia, minister to Great Britain and secretary of State. He also is said to have refused Supreme Court nominations from Presidents Tyler and Polk before becoming president in 1857, a few days before his 66th birthday.

Buchanan knew personally every president from James Madison through his predecessor Franklin Pierce, and for decades met anyone of importance who came through Washington. In the often wastrel city, he was known for hosting the best parties and he impressed even Queen Victoria and Czar Nicholas I with his fete-making.

Yet as president, Buchanan chose the wrong path at every fork in the road. Two days before he was inaugurated, he got Congress to pass the Tariff Act of 1857, which subdued manufacturing just as it was modernizing in the North. The day after his inauguration, the Supreme Court issued a ruling he had influenced behind the scenes: Dred Scott v. Sandford. The decision, which declared all descendants of slaves noncitizens and sharply curtailed the federal government’s right to regulate slavery, is generally acknowledged as one of the worst rulings ever. Buchanan, however, thought it would solve the slavery problem, not launch the nation toward the Civil War.

The uncertainty about slavery caused people to pull back on plans to settle out West in the new territories, stopping a two-decade economic boom almost immediately. Railroads and other businesses linked to the country’s expansion began to fail. Every bank in New York effectively closed, refusing to issue scrip for anything but solid gold or silver.

Buchanan’s response? He would do nothing. People deserved what they got if they were in debt or held speculative stock, he said. Eventually the Panic of 1857 would be solved, but it took the buildup to Civil War to do so.

Slave or Free Kansas? Buchanan wouldn’t take a side, leading to the murders and battles of Bleeding Kansas. John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry? Buchanan balked at sending troops until Robert E. Lee stepped in to convince him Brown’s desire to spark a slave rebellion was indeed a danger to the union. Support Stephen Douglas, the Democrats’ proposed nominee to succeed him? No, he would stand neutral, thus allowing the Democratic Party to split three ways, assuring the Republican Abraham Lincoln the election. Six Southern states seceded between election day and Lincoln’s inauguration, but Buchanan said the Constitution didn’t give him, as president, the power to do anything to keep them in the union.

Buchanan’s long government service may well have been the main contributor to his remarkably bad presidency. He was deliberative, plodding and compromising, perhaps not such bad traits for a senator or diplomat, but hardly the best behaviors for a president in a crisis.

Three men always top historians’ list as the best presidents: George Washington, Lincoln and Franklin Roosevelt. None were previously exemplars of political success. None served in the Cabinet, as senator, ambassador or judge. Washington, of course, had no opportunity for such office pre-Revolution — but both Lincoln and FDR lost bids for the Senate and Roosevelt ran for vice president and lost.

Like Buchanan, those at the bottom of presidential success lists had long elective careers: Richard Nixon was a congressman, senator and vice president. Franklin Pierce was speaker of the New Hampshire House as well as a U.S. congressman and senator. George H.W. Bush had deep elective and executive branch experience. None, certainly, distinguished himself in the White House.

No career ladder, then, ensures a president will perform well once in office. In Buchanan’s case, four decades in vital governmental posts still left him in the presidential rankings cellar. The presidency is a singular job whose best practitioners apparently are just singularly adept people.

Robert Strauss is the author of the book “Worst. President. Ever.” about James Buchanan.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.