Opinion: A bill to ban paid prioritization by ISPs makes sense, has no chance

- Share via

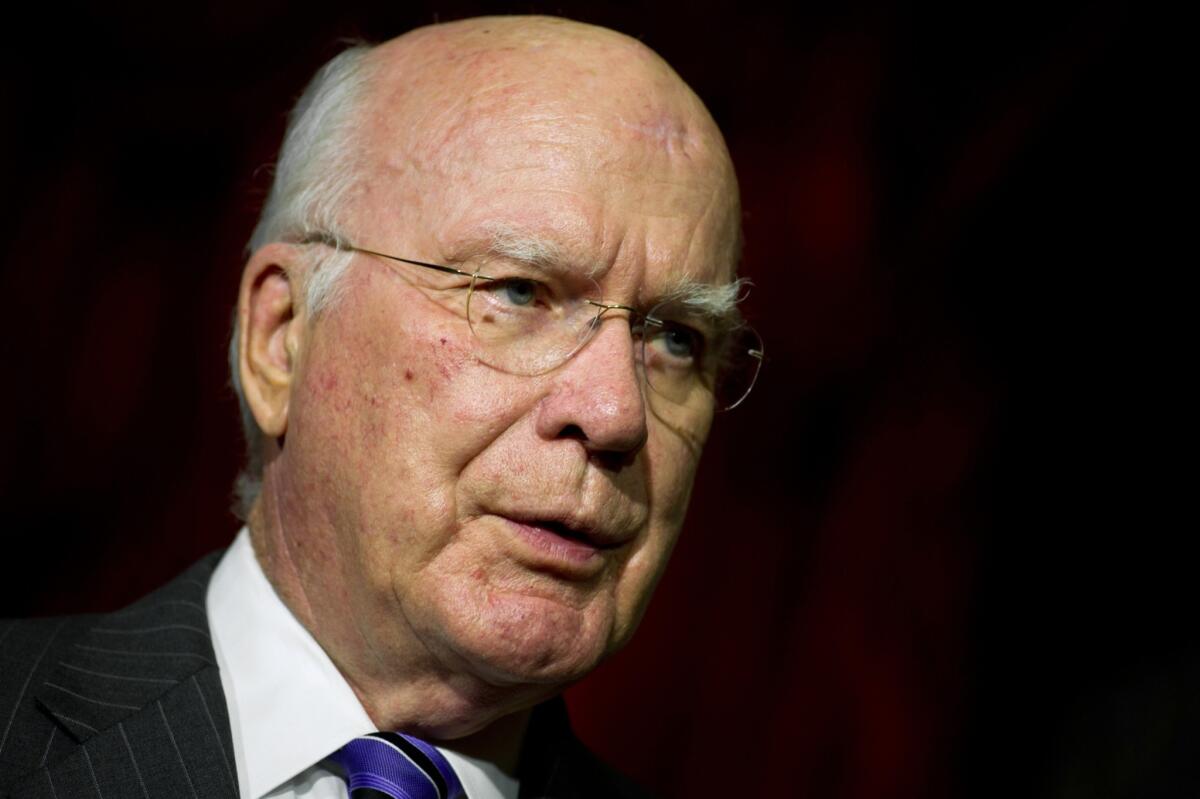

Joined by four other Democrats active on tech issues, Sen. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.), the chairman of the Senate Judiciary Committee, unveiled legislation Tuesday that charts a sensible, middle-ground path on net neutrality.

Naturally, it has no chance of becoming law.

------------

FOR THE RECORD

An earlier version of this post incorrectly referred to the proposal twice as “Rockefeller’s bill.” Sen. Jay Rockefeller (D-W.Va.) was not one of the original co-sponsors of the legislation.

------------

The Federal Communications Commission has been trying to preserve net neutrality for a decade, laying out principles and rules aimed at stopping broadband Internet service providers from interfering with their customers’ choice of online content providers, services and applications. But a federal appeals court has blocked the commission twice, saying it exceeded the authority it received from Congress.

The commission is trying again, but the rules it proposed are taking a lot of flak from both sides in the net neutrality debate. Proponents of strong rules argue that the FCC’s approach wouldn’t stop deep-pocketed content and service providers from paying ISPs to put their traffic at the head of the queue, to the detriment of upstarts and smaller competitors. Opponents argue that the commission was asserting an open-ended purview over the Net that would chill investment in broadband networks.

The legislation by Leahy and Rep. Doris Matsui (D-Sacramento), which is co-sponsored by Reps. Henry A. Waxman (D-Beverly Hills) and Anna Eshoo (D-Menlo Park) and Sen. Al Franken (D-Minn.), would give the FCC a simple set of instructions that everyone should be able to agree on. It would order the commission to promulgate regulations within 90 days that prohibit companies from paying broadband ISPs for special treatment, while also barring ISPs from giving special treatment to their corporate siblings.

The rules would specifically bar “edge providers” -- companies that provide content, services or applications online or the devices used to access them -- from paying to have their traffic prioritized over other edge providers’ data. But in ordering these rules, the bill would endow the FCC with no broader authority to regulate the Internet or ISPs.

In other words, the measure would give net neutrality proponents the flat prohibition they covet against paid prioritization. But it wouldn’t do so in the way that many of them have suggested, which would be to reclassify broadband Internet access as a telecommunications service subject to broad FCC regulation under Title II of the Communications Act of 1934. Such a reclassification is what ISPs and their allies in Congress have been most vocal in opposing.

What’s not to like?

Berin Szoka of TechFreedom, a group that advocates a deregulatory approach to technology policy, called the proposal “the worst kind of political theatre” because it orders the commission to do something Congress hadn’t given it the authority to do. “If Leahy and Matsui were really serious,” Szoka wrote in an email, “they’d propose ... statutory language that would actually provide the necessary legal authority for the FCC to regulate prioritization -- and join the dialogue their Republican counterparts have already started” about overhauling the Communications Act.

It seems strange that Congress could pass a law instructing an agency to do something without implicitly granting the agency the authority to do so. Regardless, the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals ruled in January that the commission had broad power under Section 706 of the Communications Act to regulate Internet access providers in order to promote broadband. The Leahy bill could be viewed as clarifying what Congress wants the agency to do with that authority, or it could be tweaked to refer explicitly to that section.

Anti-regulatory purists might also argue that any rules restricting ISPs would inevitably block innovation and investment to some degree. But given the paucity of choices that consumers have for broadband service today, the innovation blocked by Leahy’s bill isn’t the kind that would help the Net flourish as a platform. An ISP that prioritizes a partner’s traffic does so at the expense of other companies’ ability to serve the public. That amounts to picking winners and losers online, and it’s anti-competitive.

The National Cable and Telecommunications Assn., which represents cable TV operators, offered a noncommittal statement in response to the legislation, saying it supported “sensible but clear rules” to ensure an open Internet, and that its members “do not engage in paid prioritization.” But it also endorsed FCC Chairman Tom Wheeler’s proposal to base rules solely on Section 706 of the Communications Act. Some proponents of net neutrality argue that this approach, which would bar deals between edge providers and ISPs only if they were “commercially unreasonable,” would leave too much room for paid prioritization and Internet “fast lanes.”

Wheeler favors using Section 706 and the “commercially unreasonable” standard because such an approach could avoid the legal pitfalls in the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals that toppled the commission’s previous efforts. But David Sohn of the Center on Democracy and Technology, an advocacy group that supports net neutrality regulations, said it wasn’t enough for the rules to pass muster with the courts. If the FCC’s enforcement of those rules effectively banned paid prioritization, Sohn said, ISPs could sue the commission for applying the rules in an impermissible way.

Leahy’s bill would help the FCC fend off that sort of challenge, Sohn said. “Once you actually have Congress saying paid prioritization is unlawful, I think the FCC would be on stronger ground,” he said.

In a way, the proposal is a litmus test for ISPs that say they support an open Internet and don’t plan to create fast lines but can’t accept the burdensome regulation of Title II, much of which was crafted in the 1930s. But then, the same could be said of the FCC’s 2010 net neutrality rules, which barred ISPs from blocking or unreasonably discriminating against any legal content, app or service online. Those rules, which broadband ISPs helped craft, were deemed tolerable by many broadband providers. It only took one, however -- Verizon -- to bring the lawsuit that successfully challenged the FCC’s authority to adopt the strictures.

As the cable industry’s statement indicates, ISPs aren’t ready yet to give up on Wheeler’s proposal and the flexibility it could provide to strike deals with edge providers. And as the lack of Republican co-sponsors indicates, net neutrality is a politically polarized issue. So the odds that broadband providers and their GOP allies will give Leahy’s bill the support it needs to move through Congress in an election year lie somewhere between nil and zero.

Follow Healey’s intermittent Twitter feed: @jcahealey

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.