Trump has shadow-boxed cartoon enemies for years. It’s no surprise others are taking up real arms

- Share via

With more than 30 civilians murdered last week in massacres in California, Texas and Ohio, the rampages across the country have been widely denounced as terrorism.

On Sunday, federal officials announced they were treating the El Paso shootings “as a domestic terrorism case, and we’re going to do what we do to terrorists in this country, which is deliver swift and certain justice.” Ivanka Trump used even more sinister language: “White supremacy, like all other forms of terrorism, is an evil that must be destroyed.”

It is imprecise to equate an ideology, white supremacy, which apparently motivated at least one of the attacks, with a tactic, terrorism. But it is also understandable. Terrorism is a notoriously slippery word. And of course, politicians, on the spur of the moment, use the word “terrorism” chiefly to signal their outrage and toughness.

So is it useful to call the mass murders in the U.S. terrorism?

The three gunmen were certainly unlawful combatants using violence against civilians.

They also professed or had studied extremist ideologies of one sort or another. The suspect in El Paso posted a manifesto saying the attack was “a response to the Hispanic invasion of Texas,” according to police. Less is known about the Gilroy, Calif., gunman, but he had posted an online recommendation for a discredited book on social Darwinism that justified slavery. The Dayton, Ohio, gunman played in a “pornogrind” band that performed misogynistic songs with themes of gore and brutal sexual assault. He also reportedly kept a “rape list.”

But does committing violence against civilians and possessing an extremist ideology automatically make someone a terrorist?

The tactic of terrorism has generally been used by those resisting a government or an occupying army.

During the French Revolution, when terrorism got its name, political violence by the lower classes was part of a campaign to panic the upper classes, and shake the monarchy out of power. In Northern Ireland in the 1960s, the Irish Republican Army regularly committed violence against the British army, whom it considered occupiers, as well as Protestant civilians, whom it perceived as aligned with the British.

In this context, the narrative of recent mass murderers in America is supremely incoherent.

That is, unless there is an imagined occupation in the U.S.: a cultural one, if not a political one.

In the El Paso suspect’s online writing, he expressed a fear that Trumpism wasn’t long for this world. “The Democrat party,” he wrote, “will own America and they know it.”

The Gilroy gunman complained that nature had been destroyed and was now “overcrowd[ed]” with “hoards of mestizos and Silicon Valley white” people (though he used a gendered epithet for “people”).

Though the Dayton shooter described himself as a leftist hungry for a socialist uprising, all three of these men last week seemed to believe that some group of interlopers — either people of color or feminized elites or both — had seized control of the country.

The panic about a phantom occupation cuts across the political spectrum. It doesn’t matter who’s in power in Washington, the thinking goes: American culture is increasingly dominated by a conniving overclass, imagined variously to be headquartered in Silicon Valley, the banks, the media, major American cities, academia and Hollywood.

In the U.S., one common catchall word for the enemy is “political correctness.”

Last week in an article in Politico, Tim Chapman, the executive director of Heritage Action for America, a conservative lobbying group, cited polling that found a strong aversion on the part of most voters to “political correctness” as the scourge of — well — everyone. Eighty percent of voters in the middle of the spectrum, according to polls, are averse to political correctness. And more than three-quarters of Republicans, according to Heritage Action’s own data, said it was a “major” problem.

Political correctness is an imaginary ideology espoused by exactly no one. It’s said to have something to do with Marxists — or maybe with identity politics, the nightmare of many Marxists. As nebulous as it is as a concept, it’s the name for a secular Satan — for whatever occult force has seemingly hijacked the nation. Women, people of color, and certain white male elites (disparaged with emasculating language) are often the face of this force — and the ones frequently targeted by mass murderers.

What makes the attack on political correctness so disturbing is that the ideology doesn’t exist anywhere but in the radioactive contempt for it.

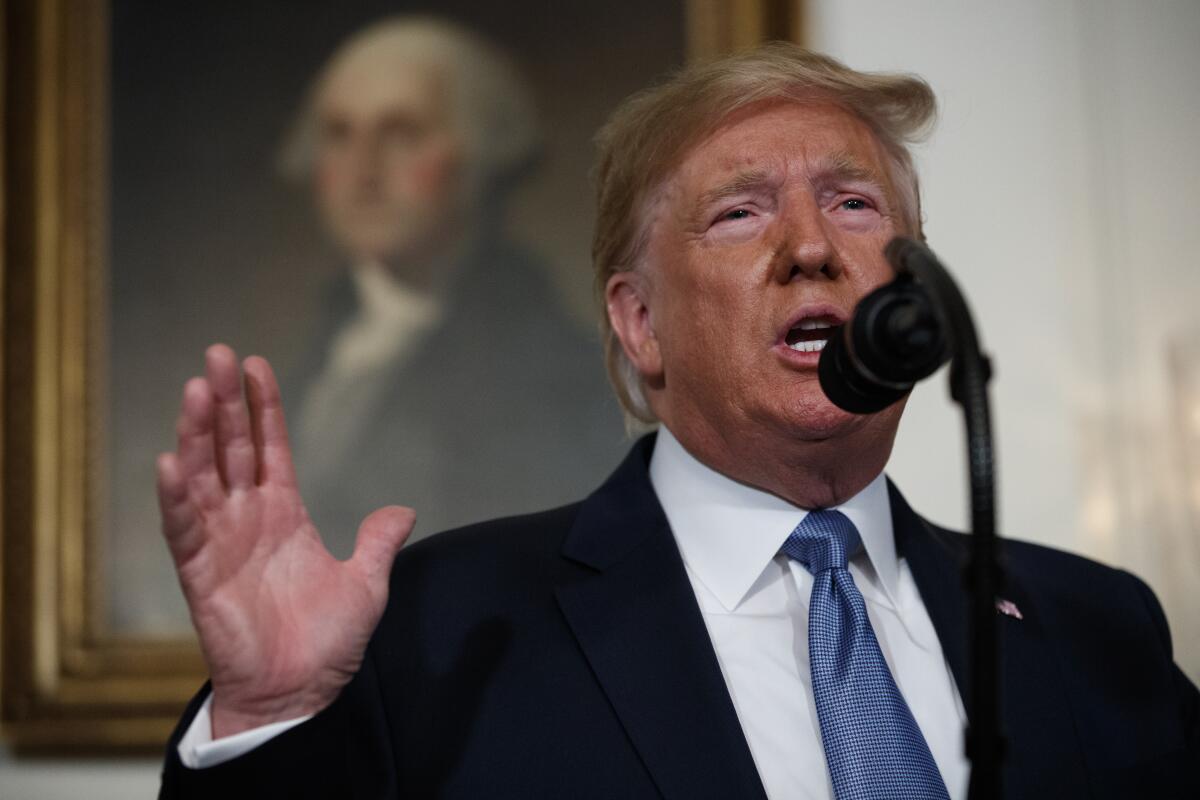

In the past three years, Trump has taught Americans of every stripe to ignore our actual interests — peace, prosperity, education, social harmony — in favor of shadowboxing with cartoon enemies that dance around in his head.

It should come as no surprise that, for three years, extremists have blown past shadowboxing and taken up arms against the P.C. phantoms.

But, because these figures don’t exist, they’ve had to shoot civilians at random, and tell themselves they’re part of a revolution.

Twitter: @page88

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.