Two pioneering reporters demonstrated the importance of covering all parts of L.A.

- Share via

In 1962, the Los Angeles Times’ managing editor, Frank McCulloch, assigned a white reporter named Paul Weeks — a passionate civil rights supporter — to cover Black Angelenos, whose numbers had burgeoned as African Americans migrated to California to work in defense plants.

It might seem strange that a white reporter was assigned to the job, but at the time, the paper had no Black reporters, and it didn’t occur to The Times’ white male masthead that they should hire any. Prior to his assignment, Weeks recalled to retired Times city editor Bill Boyarsky for his book about The Times, “Inventing L.A.,” “The Times would not even send reporters into Black neighborhoods.” There was, to put it mildly, some skepticism in The Times’ newsroom about Weeks’ assignment.

Our reckoning with racism

As the country grapples with the role of systemic racism, The Times has committed to examining its past. This project looks at our treatment of people of color — outside and inside the newsroom — throughout our nearly 139-year history.

Weeks also told Boyarsky that he was regarded with suspicion at first by Black Angelenos, who had come to expect nothing but dismissive coverage, if any at all, from The Times. Rarely had the paper given the rest of Los Angeles insights into the lives of people who lived in a part of town many white suburban Angelenos referred to as “down there,” nor to the realities of life in a broad swath of South L.A.

But Weeks was engaging and persuasive, and because he talked to real people and not just officials and theorizers, his stories were insightful and informed — and worrying. He wrote about how the civic, cultural and business institutions in Los Angeles were paying little attention to its many Black citizens. He interviewed James Baldwin when he came to town for the opening of one of his plays, and he wrote about housing discrimination and attempts to integrate Hollywood production.

Weeks was taken off the beat in 1964, two years after he started it. As he explained it to Boyarsky, he had protested when a Black reporter for the Los Angeles Sentinel was barred from covering a segregationist group. His editors said Weeks had refused to cover the meeting, so they changed his assignment. But Weeks always wondered whether part of the problem was that he had also begun looking closely into bad police practices, which would certainly have rubbed some Times editors the wrong way.

Boyarsky said Weeks warned his editors, “This town is going to blow up one of these days, and The Times won’t know what hit it.”

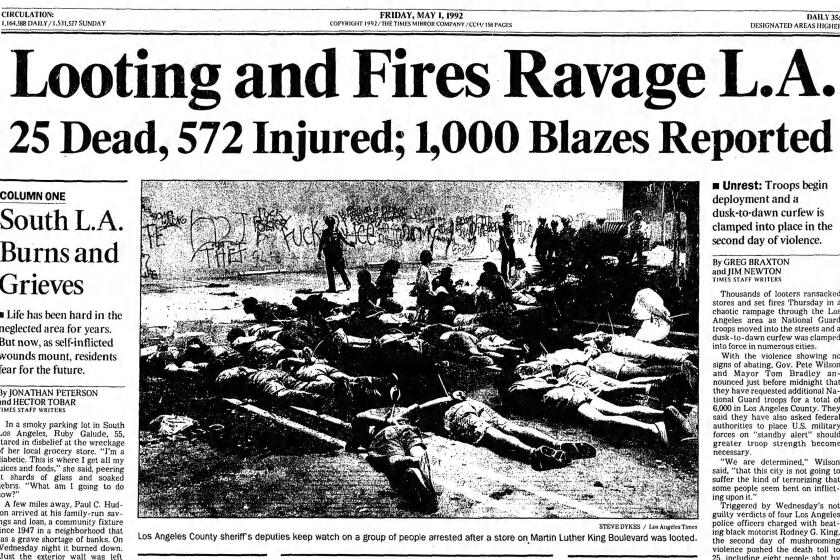

“One of these days,” as it turned out, came just a year later, when a California Highway Patrol traffic stop in Watts in August 1965 sparked such an outpouring of frustration and anger on the part of many of the area’s Black residents that what the paper headlined in one edition as widespread “Negro Riots” quickly erupted.

The Times still had no Black reporters or editors. What it did have, by sheer happenstance, was a Black advertising messenger named Robert Richardson, who came into the newsroom one evening during the riots eager to tell someone what he saw going on in his neighborhood.

The paper thereafter ran gripping first-person accounts Richardson called in from phone booths in the heart of the unrest. Under his byline the editors added a note: “Robert Richardson, 24, a Negro, is an advertising salesman for The Times.”

He worked to explain the anger in Black Los Angeles to the white newsroom and white subscribers. “Maybe part of the explanation lies in the fact that for so many Negroes who have come here believing Los Angeles to be a city of golden opportunity,” he wrote, “the promise has become a myth.”

Once the rioting ended, Richardson was taken on as a reporter-trainee, but how much training he got, who knows? Sent to cover breaking news like fires, he felt unprepared, thrown into the deep end. “I was scared to death every night,” he once said.

Richardson felt to a severe degree some of the pressures that even better-trained, better-prepared Black journalists would feel in years to come at The Times: So few were their numbers that they were expected to epitomize, all by themselves, the entire Black community.

As Richardson struggled to stay afloat in the newsroom, he was being lauded in the Black community — pressured in different ways from both sides. But by the time The Times won a Pulitzer Prize in 1966 for its coverage of the unrest, Richardson, whose work was part of the winning news package, was gone from the newsroom.

The backstory was that he had been arrested on a misdemeanor charge that came to nothing — the most reliable account is that it was for stealing a hotel ashtray — and that he resigned in exchange for the paper getting him out of jail.

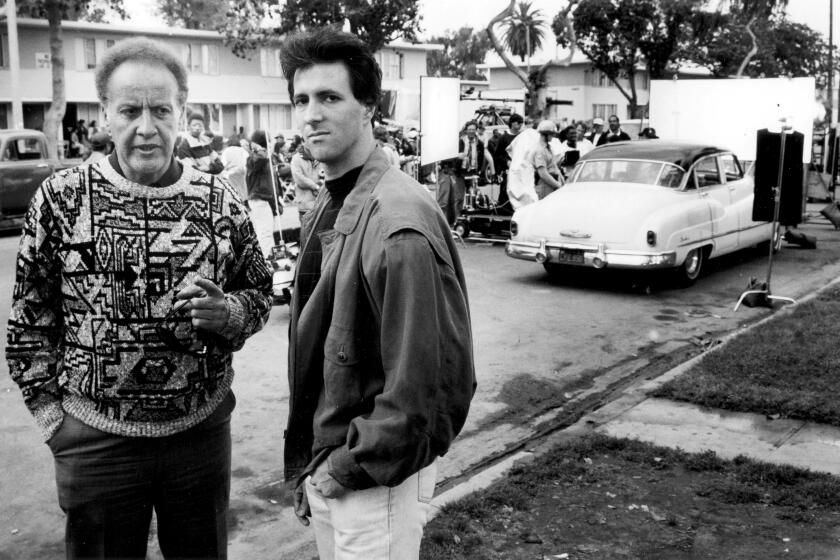

Richardson told his story two decades later when Times staffer Penelope McMillan, who is white, happened across him while reporting on a homeless encampment. In 1990, a TV movie based on his life earned him more than $50,000 as a consulting fee, but it couldn’t stop him slipping in and out of homelessness and alcoholism.

The Watts riots and the civil rights movement began the gradual divorce between the police and the press in L.A. In the old days, the relationship had been so cozy that police reporters had been issued official LAPD badges that read “reporter” in place of “patrolman.”

Neither Richardson’s nor Weeks’ name is very familiar to present Times staffers, but each still makes his presence felt to this day: Weeks, for making the paper acknowledge and cover in a more forthright fashion the community it had so long ignored, and Richardson, for showing how vital it is to hire reporters from different backgrounds, especially those with roots in underreported communities.

In the half-century since they worked in The Times’ newsroom, the paper has, haltingly, and with many mistakes, tried to make their lessons into policy, practice and progress. That effort continues.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.