If Biden wins how much can Trump accomplish during his last months as president?

- Share via

In the final days of his presidential campaign, President Trump’s unorthodox behavior has been on full display — from attacking Anthony Fauci to threatening to fire the FBI director. As down-ballot Republican candidates and strategists tear their hair out over a president who resolutely refuses to take advice, Trump’s behavior triggers a fundamental question for the rest of us: If he loses, what can he do in the three months between election day and Inauguration Day?

The answer is — not much. Thank you, Founding Fathers, who after experiencing monarchy under King George III, revolted and then designed a system of checks and balances to curb the power of one individual. Everyone who has ever worked in a White House has come up against these checks. But because the president reigns supreme in the media, we often forget that he is still subject to what scholars refer to as “veto points” — from the Congress, the courts or established laws that govern what the executive branch can do. Presidents with substantial political capital have trouble getting their way; presidents who are lame ducks have even greater trouble.

If Trump loses, he will be severely constrained in almost all areas except for one. He can issue pardons. He has already said he would consider pardoning individuals who have been indicted and convicted in the Russian investigations. But he can pardon only people convicted of federal crimes. And he will be powerless to pardon himself once he is no longer president, should the state of New York’s investigation into the Trump Organization’s finances result in prosecution and conviction.

Trump mixes flattery with insults as he tries to appeal to women in the final days of the campaign.

But, when it comes to other powers, Trump will be somewhat hamstrung. First, with the possible exception of a bipartisan deal on another COVID-19 stimulus package, he will not be signing into law any substantial pieces of legislation. With control of the House in Democratic hands and control of the Senate in Republican hands until Jan. 3, forget any legislation that is not clearly bipartisan.

Next, of course, come the courts. The Trump administration has won and lost in the courts. Most recently the Republican Party brought an unprecedented number of lawsuits against the states as they have been adjusting their voting procedures to the pandemic. But their record there has been mixed — as it has been in other areas of policy such as healthcare.

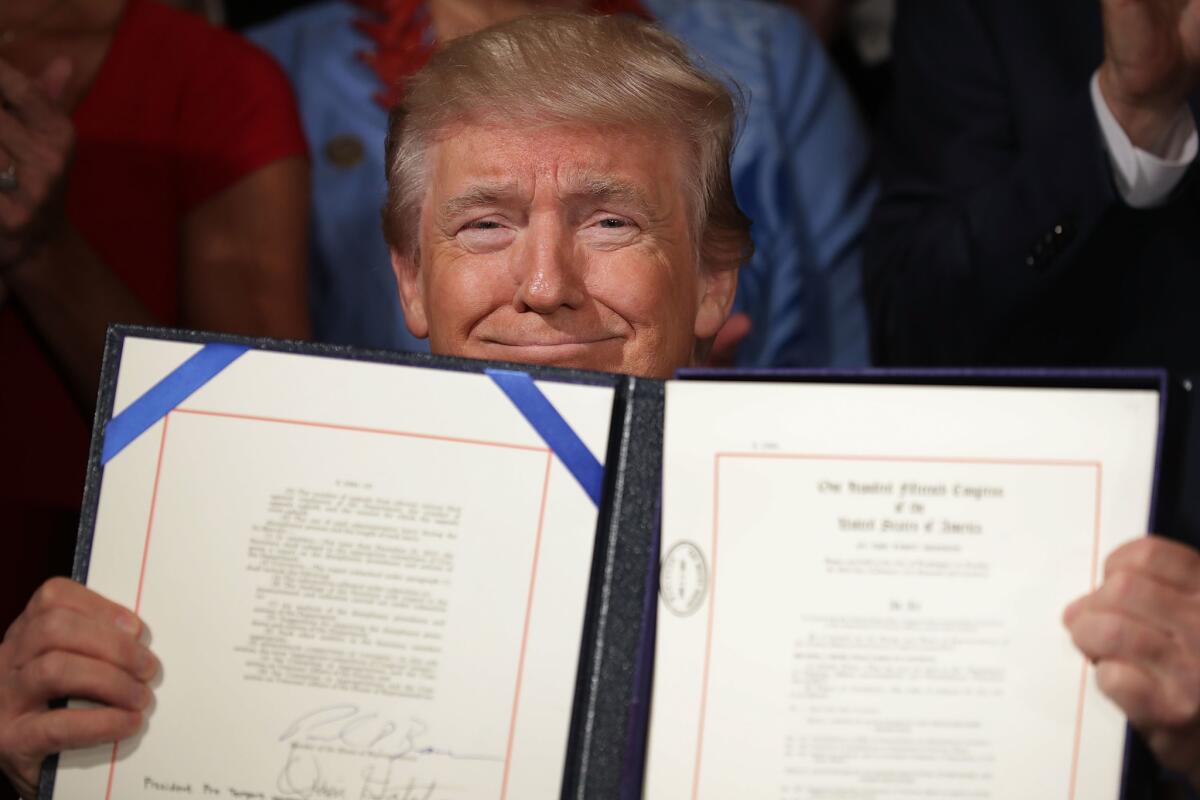

This means Trump is left with executive branch levers of power. Chief among these are executive orders that are the last refuge of weak presidents simply because they have no long-lasting value — they can be overturned or reversed as soon as the next president comes in.

Additionally, most executive orders require changes to regulations or the creation of new ones. This is not a simple process — it begins with a notice of proposed rule-making and can take months if not years. For example, out of 78 executive orders Trump has issued that focus on the environment, only 30 are in effect. The others are either in process or have been repealed or withdrawn — often after the administration lost in court.

And moving an executive order through the process is very difficult without a skilled and loyal team in the agencies. The Trump administration has seen more turnover among presidential appointments than any other president in the past 40 years in both the Cabinet and in top-level White House officials. The same is true of sub-Cabinet-level jobs. At the beginning of this year the Trump administration had vacancies in 170 out of 714 key positions. He simply doesn’t have the team in place to execute complex last-minute changes.

Finally, bureaucracy itself can stymie a president. For instance, Trump has been hoping to announce a successful vaccine for the coronavirus before election day. So when the Food and Drug Administration wrote guidelines that would govern when a pharmaceutical company could get emergency-use authorization to begin distributing vaccines, the Trump administration tried to block them because it would mean release of the vaccines after the election. The attempt to politicize a scientific process was not well received by FDA employees, and the organization, in defiance of the White House, went ahead and published the vaccine guidelines, which the Trump administration then “approved” after the fact.

The biggest bureaucracy, the United States military, is similarly resistant to presidential influence. In early October, Trump tweeted that he wanted to bring the troops in Afghanistan home by Christmas — something that no one in the Pentagon was talking about. It was later suggested that the Christmas timeline in the tweet was aspirational — by none other than the president’s own national security advisor — after it became clear that the Pentagon wasn’t going along.

Bottom line? Trump is not King George III. The Founding Fathers made sure of it.

Elaine Kamarck is a senior fellow at the Brookings Institution and author of “Why Presidents Fail and How They Can Succeed Again.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.