Learning as meditation in a Zoom classroom

- Share via

How do you get college students learning?

I run a cognitive science research lab where I study mind and language. Throughout my teaching career, I have always gone old school, the Socratic way. Throw a big challenge in the classroom, and with some gentle probing, slowly guide students on to discovery. Teaching and research share this common path. All major revelations spring from a delicious puzzle.

So when the coronavirus pandemic hit, I just couldn’t see how any of this could work online. Like everyone else, I had to bite the bullet on remote teaching. And of course, I, too, suffer from acute Zoom fatigue. But over the semester, I’ve found unexpected benefits from the online experience.

For starters, just before the first day of class, I had several students visit my remote office hours — an unprecedented event in the “in person” era. Then, in class, I was struck by the students’ hunger to be intellectually challenged. I see their faces watching me as I speak. Many weigh in, level challenges, and at the end of class, even stop to thank me.

I am not sure why my students have turned more attentive, but I can offer a few speculations.

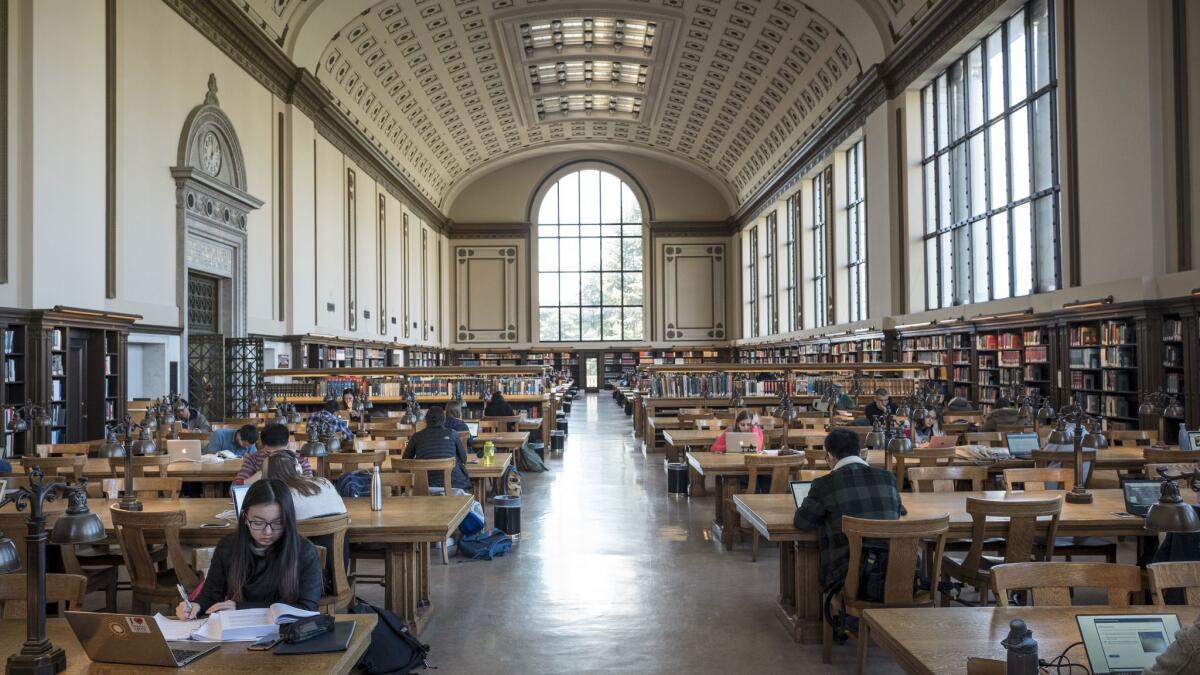

In the old days of teaching in large lecture halls, students would mostly take middle and back rows — who wants to sit right under the professor’s nose? So my students would skeptically gauge me from the Olympian heights, and I would preach up to the Gods, working hard to gain their trust and interest.

Zoom instantly erased all of that. My students and I literally see each other eye to eye, and I can finally speak as one would converse with a friend sitting across the coffee table. There is much more closeness and intimacy. Everyone is right there in the first row, best seat in the house.

While online teaching engenders closeness, it also offers the opportunity for just the right amount of distancing. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg said that, in a good marriage, one sometimes needs to be a little deaf. Her wisdom applies to classroom teaching as well.

Despite my best efforts in the lecture hall, occasionally, one of my students would get distracted and even nod off. It’s all normal, but when it happens right in front of me, I momentarily lose my focus. Zoom reduced the six-foot dozing distraction to a 2-by-2 square on my screen. I can get the closeness I always desire, and the deafness I sometimes need.

The pull and push between distancing and closeness is only one part of the story. Among my students nowadays, I also see more maturity, kindness and eagerness to learn. Their essays seem to me more thoughtful and their questions more probing. We seem to connect better. I believe this side effect has nothing to do with Zoom, but everything to do with the pandemic.

Earlier this year, we saw our academic and cultural institutions shut down overnight. No more concerts, museums and libraries. Our focus of attention has shifted abruptly toward the singular goal of protecting our bodies against the invading virus. We now anxiously monitor every change in our health, nervously jumping as we hear a passerby cough or sneeze. The public life of the mind has taken a backseat for a while.

The heightened concerns about our physical safety have also hit us in a political climate that blurs the boundaries between truth and lies, science and fiction. This combination is psychologically difficult for us to take because we naturally align the self with the mind, and we define it in moral terms.

The longer we spend protecting our bodies from the COVID-19 menace while trying to confront the political attack on facts, the stronger the urge to reaffirm our identity by engaging with truth and the life of the mind. Learning, even if remote, does both, and for this reason, it is restorative. It bolsters our psychological core, just like meditative practice.

When my students log into my class this semester, I feel we are on a common quest. Yes, they are in the class to learn about the science of cognition. But in many ways, their true task is also personal and far more urgent.

Iris Berent is a professor of psychology at Northeastern University. She is the author of “The Blind Storyteller: How We Reason About Human Nature.”

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.