Kevin McCarthy lauds the first Black member of the House. Here’s why that’s annoying

- Share via

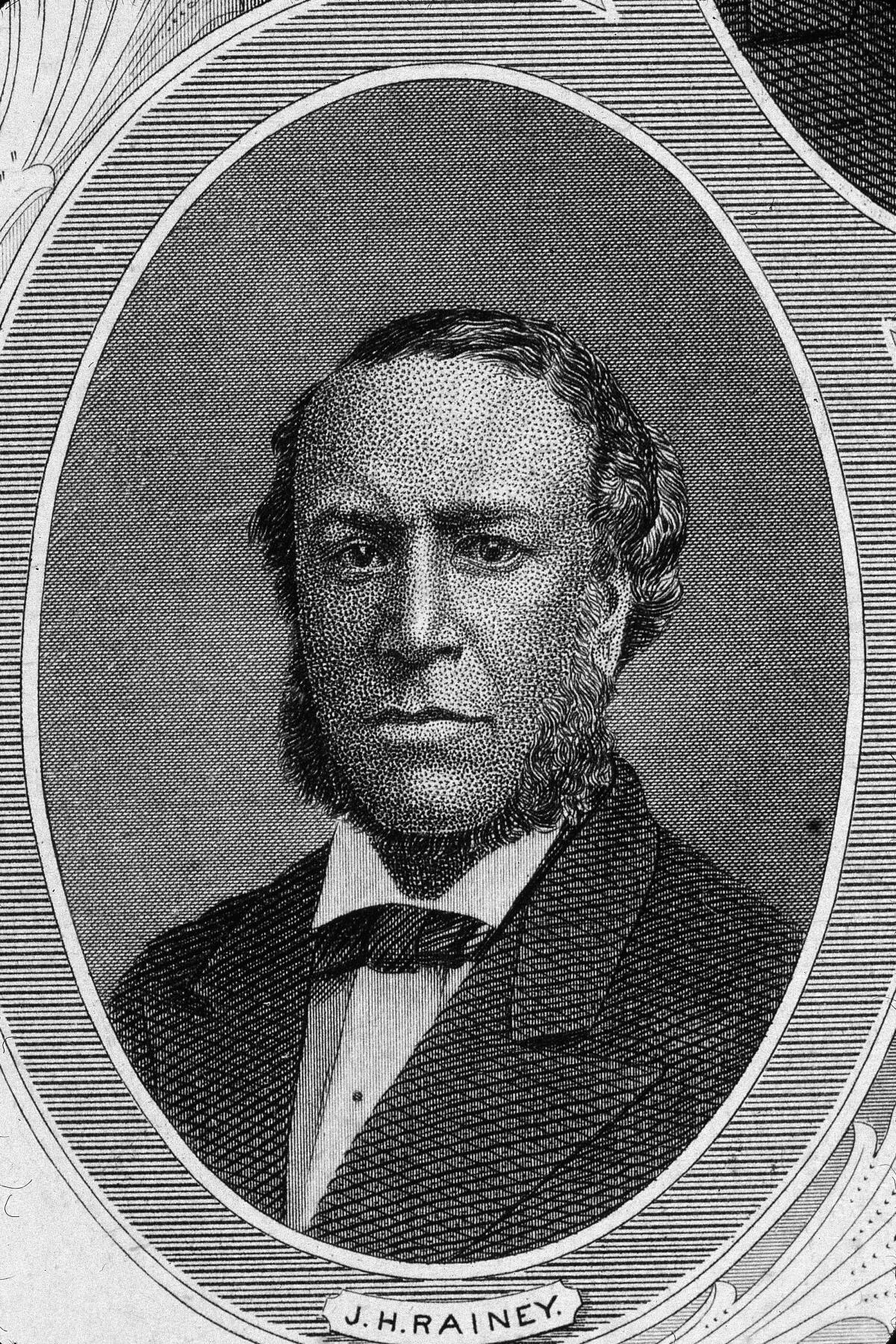

House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy (R-Bakersfield) recently gathered reporters together to say a few words about Joseph Rainey of South Carolina, the first African American member of the House of Representatives, who was sworn into office 150 years ago this Saturday.

On the face of it, it was a straightforward tribute to a mostly forgotten but groundbreaking figure — a formerly enslaved person who served four terms in Congress, where he helped pass legislation to suppress the Ku Klux Klan and defended the rights of newly freed African Americans. When Rainey took the oath of office on Dec. 12, 1870, the New York Tribune reported that “the hum and buzz of voices ceased on the floor” as members turned to watch the first representative of “the newly enfranchised race.”

Rainey is certainly someone to celebrate, but McCarthy’s words felt disingenuous and irksome.

Would he have honored Rainey if he hadn’t been a Republican? Fat chance. McCarthy was there on behalf of the party — to flog its connection to a more noble past. He expressed pride “as a Republican and an American” that the party was “continuing the legacy of the first African American to ever serve in Congress.” He referred to the GOP — as Republicans love to do — as the “party of Lincoln.”

It’s not inaccurate to call the Republican Party the party of Lincoln. It was Lincoln’s party — founded in 1854 in opposition to the expansion of slavery. When Joseph Rainey took office during the Reconstruction era after the Civil War, it was the “Radical Republicans” who fought the Democrats to expand the rights of the former slaves.

Of course Rainey was a Republican. Black Southerners overwhelmingly were.

But what Kevin McCarthy conveniently neglected to mention is that the GOP hasn’t been the party of African American voters for a very, very long time. And there are good reasons for that.

At a moment when the nation is again roiled by racial unrest, and Republicans have just lost another presidential election with less than 10% of the Black vote, it is understandable that McCarthy would want to bask in the fading 150-year-old glow of Joseph Rainey and Charles Sumner and Abraham Lincoln and others who fought on the right side of history.

But that was long ago.

Losing the support of African American voters was a slow, extended process. But through hard work and bad decisions, the party managed it.

It began, you could say, while Rainey was still in Congress — when President Rutherford B. Hayes, a Republican, agreed in 1877 to withdraw all federal troops from the South in exchange for Southern Democratic support. With that, Reconstruction was officially over and white supremacy made its comeback in the South.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Black voters slowly began moving away from the Republican Party. As they moved north in the Great Migration, Democratic political machines seeking to absorb them began to think about how to serve their interests.

Many African Americans still shunned Democratic candidates, whom they associated with Southern bigotry. But in 1936 they shifted their support dramatically to President Franklin Roosevelt, a Democrat, whose New Deal policies helped Black Americans facing deep poverty during the Great Depression.

Over the next few decades, Republican strategists began shifting their focus to white voters in suburbs and in the South.

It was President Lyndon Johnson, a Democrat, who signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965 into law. His Republican opponent in the 1964 election, Barry Goldwater, not only voted against the Civil Rights Act, but also boasted of that vote in his campaign.

When Richard Nixon ran for president in 1968, he too adopted what was known as the “Southern strategy,” playing on racial fears of Black violence to win white votes across the South. In 1980, Ronald Reagan spoke up for “states’ rights” during a speech in Mississippi and, in 1988, George H.W. Bush capitalized on racist tropes with his Willie Horton TV ad.

It took a long time for Black voters to fully abandon the Republican Party. But now, 83% of African Americans consider themselves Democrats or lean that way, according to the Pew Research Center; only 10% identify as, or lean, Republican. And Black voters haven’t given more than 15% of their votes to a Republican presidential candidate since 1960.

Today, Congress is more diverse than it ever has been.

A record number of African Americans are serving — 54 in the House and three in the Senate. And Kevin McCarthy, take note: About 90% of the nonwhite members of Congress today are Democrats.

It doesn’t have to be that way forever. Democrats don’t have a permanent lock on the Black vote. When Bill Clinton undertook to “end welfare as we know it” and again when he signed 1994’s tough-on-crime bill, he faced significant criticism. African Americans have also complained that Democrats take them for granted (including this year, when Joe Biden said presumptuously that any Black person considering voting for Trump “ain’t Black”).

This year, Donald Trump hosted a more diverse cast of speakers at the Republican National Convention. And in the election, he made gains, on the margins, with nonwhite voters, and especially with Black men.

If McCarthy and the GOP want to engage in a real competition for the votes of African Americans, I say — go for it! But I suspect they’ll have to do more than trot conservatives of color onto the convention stage and brag about what Republicans stood for 150 years ago.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.