The kids who aren’t all right — the pandemic’s lasting toll on youth mental health

- Share via

On a busy night shift in the psychiatric emergency room, during a monthlong psychiatry rotation for medical school, I first met my patient, a teenager.

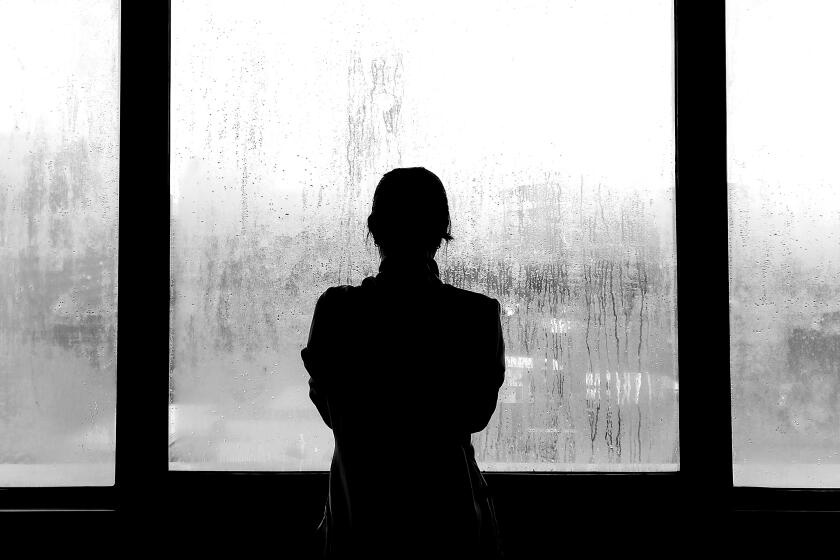

She was hunched over a stretcher at the far end of the hallway. Before the pandemic, she spent lots of time with her friends and loved going to school. Then COVID-19 lockdowns turned school virtual, and she was staring at herself for hours on end on Zoom. She told me that she became displeased with her appearance on the screen, comparing herself to her peers at every possible instance.

As her self-loathing thoughts intensified, she became more isolated and began restricting her food intake. She lost more than 50 pounds, and her feelings of inadequacy worsened. She began cutting herself. After her parents found her pacing up and down the roof of her building, they brought her to the ER.

During my psych rotation, I saw patients of all ages, but I was alarmed by how many of them were tweens and teenagers. I saw firsthand the harsh mental toll the pandemic has taken on young people. A recent study from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention found that mental-health-related visits to emergency rooms between April and October 2020 increased by 31% among youth ages 12 to 17, and by 24% among children aged 5 to 11, compared to 2019.

What concerns me most about the narrative around youth mental health is the idea that kids are resilient and thus eventually will recover from the stressors of this past year without mental health support.

Children are resilient, but they are also vulnerable, and I have seen how setbacks that might barely register for an adult can have an outsized impact on some adolescents. I worry that too many parents are relying solely on the resilience of childhood and are not learning to recognize early signs of emotional trauma among young people who have been separated from friends, teachers and the structure of in-person schooling.

Many of the young people that I cared for in the psychiatric ER identified as transgender or nonbinary, or were questioning their gender or sexual identities. Schools can often be a haven for these teens, a place where they can express themselves and find acceptance among their peers. For many of these patients the isolation of the pandemic meant staying home with family members who at best didn’t support them, and in some cases berated them and refused to accept them.

One transgender patient described daily intolerance, including being forced to do what their parents described as gender-conforming chores to “fix my confusion.” They spiraled into a major depression and attempted suicide several times.

For some of my young patients, it was the unexpected deaths of family members from COVID that severely affected their mental and emotional health, leaving them distraught and suicidal. I saw pediatric patients who were estranged from their surviving parent and thus had nowhere to go after their primary caregiver died. One patient, who lost a parent, didn’t want to “burden” the surviving parent with overwhelming financial or parenting responsibilities.

Scott Hadland, a pediatrician and addiction specialist at the Grayken Center for Addiction at Boston Medical Center, told me he has seen similar issues in his practice. He said pandemic-related school disruptions, isolation from friends and loss of daily structure and support systems have all contributed to a rise in eating disorders and substance use.

“While we’re obviously seeing a lot of repercussions of the pandemic on pediatric mental health now, this is not necessarily a short-term issue,” Dr. Hadland told me. “I fear that the worst may be yet to come.”

Parents, guardians and friends of young people need to understand the gravity of the mental health crisis swirling around them and learn to recognize and discuss mental health issues before an emergency-room-level crisis.

Just as parents and teachers would notice and react if a child has a fever or physical symptoms of an illness, they should pay attention to a child who is regularly indicating that they feel down. Small mood or behavioral changes can be early warning signs of depression or other mental health issues. Adults can consult pediatricians, adolescent psychiatrists or school counselors or reach out to community health resources such as Crisis Textline for advice.

Many kids feel vulnerable when deprived of routines and social interaction. Creating a home environment where family members regularly talk about their feelings and sharing your own worries to show that it’s OK to talk about anxieties can help the teenagers in your household. The pandemic’s toll will not end with the broader reopening and vaccination, so it’s important to keep checking in, even after pre-pandemic routines return.

In April, on the last shift of my psych rotation, I walked down the ER hallway to see a few new teenagers who had come into the triage area. The stories were just as devastating as they had been on my first day.

My last patient was suffering from malnutrition, worsening depression and suicidal ideation. Several family members had lost their jobs during the pandemic, and food insecurity meant skipping meals. After I finished my initial assessment, I asked if there was anything else we could help him with right then. “Yes,” he said, with a hint of a smile. “Can you please make this pandemic end?”

For so many young people, COVID is very far from over.

Why is it so hard to find help for those who are mid-fall? Why do we wait until they hit rock bottom?

Lala Tanmoy Das is a medical and doctoral student studying the neurobiology of addiction in New York City. @TanmoyDasLala

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.