The California recall process is reckless. Here’s how to modernize it

- Share via

When voters ratified the statewide recall in October 1911, California led the nation in innovative governance. Until then, direct democracy mechanisms had mostly been reserved for local governments, such as New England town halls. The Progressive Party, with Gov. Hiram Johnson of California as its most outspoken champion, proposed the recall as a means for citizens to bypass political corruption and railroad-baron dominance of the state legislature.

What was path-breaking and innovative a century ago, however, looks anachronistic and downright dangerous today — regardless of the outcome of Tuesday’s gubernatorial recall election. In these times of intense party polarization, we should be wary of mechanisms that enable electoral losers to win back power through outlandish means or to derail the governing agenda of a popularly elected officeholder.

While California is one of 19 states with a recall process, the combination of its rules makes it uniquely susceptible to gamesmanship. Those seeking a recall do not have to show malfeasance or incompetence on the part of the officeholder, as they do in eight of these states; they can simply claim poor performance. They can also propose a recall petition at any time whereas some states do not allow recalls in the first year or last year of office.

California also has a longer period for gathering signatures (160 days) than most other states, and this period was extended by an additional 120 days for the current recall because of the pandemic. Perhaps most important, California requires the smallest fraction of votes cast (12%) in the last gubernatorial election of any state.

Simply put, California makes it easy for a small, motivated group to trigger a recall because they can do so for any reason, they have plenty of time to do it, and they only need a small fraction of the electorate to sign a petition.

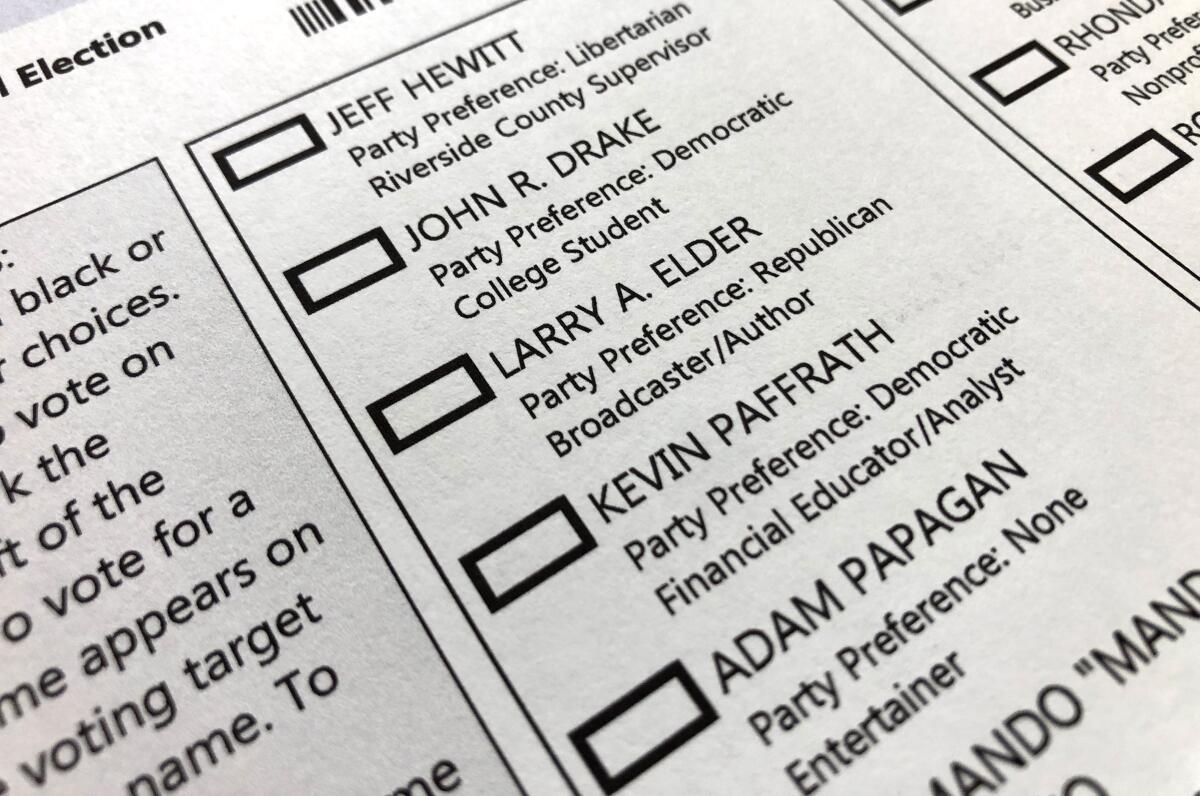

California’s recall also has the potential to make a mockery of majority rule. It is one of only two states (Colorado is the other) that prevents the current officeholder from appearing on the list of qualified candidates should the recall succeed. As a result, the incumbent can lose on the recall question with just one vote short of 50%, while a second ballot with a crowded field can produce a governor who has only a sliver of the total vote.

Polling by the Public Policy Institute of California already shows significant voter support for reforms like increasing signature requirements, instituting a runoff election, or confining the recall for illegal or unethical activity. PPIC’s poll from July 2021 also indicates significant dissatisfaction with the current recall, with the vast majority of California voters, including 69% of independent voters, viewing it as a waste of taxpayer money. The state Department of Finance estimates that the election will cost $276 million.

Instead of brushing off the current recall as a farce, Californians should view this as an opportunity to modernize our system of direct democracy. Just as the reformers in 1911 instituted direct democracy mechanisms to rectify the excesses of political corruption, we can redesign the recall to meet the needs of future Californians.

What kinds of reforms should we prioritize?

First, we can learn from the example of many other states, where a recall petition triggers a special recall election and the incumbent then appears among the list of replacement candidates. These candidates can either appear on the same ballot, as five other states allow, or they can appear in a second special election, which is the model in seven other states. California would also be wise to raise the bar for signature gathering, either to the 25% threshold as in most other states or the 20% threshold currently in place for triggering a recall election of California state legislators.

California could go even further, building on innovations it has enacted in the last two decades. Instead of running the risk of producing a winner with a small share of the vote, the state could use a modified version of its “top two” primary system in which the top two candidates, regardless of their party affiliation, get to compete in a runoff election. Alternatively, it could carry out an instant runoff system, currently in place in several California cities, where voters get to rank candidates from top to bottom, and the election produces a winner with a majority mandate without requiring a costly runoff election.

California could also impose a time limit to these constitutional reforms, having them expire after a period of years, unless explicitly re-authorized by voters. California has had such “sunset” provisions in statutory initiatives before — the temporary tax increase in Proposition 30 is a prominent example. There is nothing preventing voters from doing the same in a constitutional initiative. This innovation would allow California voters to try new ideas without saddling future generations with outdated designs and would ensure that political reforms remain responsive and relevant to future challenges that we cannot yet foresee.

Henry Brady is a professor of public policy at the Goldman School at UC Berkeley. Karthick Ramakrishnan is a professor of public policy at UC Riverside.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.