Essential Politics: When national and local collide

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Last week, I wrote about national politics through a California lens. What guided my analysis was the idea that, as the Golden State’s influence increases in Washington, a West Coast point of view could help us untangle issues on Capitol Hill.

But what we didn’t have room to get into was that this exchange of ideas and perspectives goes both ways. California is making its mark on Washington — and the politics of Washington are making their mark on California.

Local races taking on the contours of national politics isn’t a new concept. But if the 2020 national races marked a distinct, rapid change in California’s standing, the change in local politics was just as pronounced.

Local government experts told me they noticed a strong and growing polarization in smaller races, one not unlike the disputes between the center-left and progressive wings of the national Democratic Party. Local candidates were talking about some of the same issues up for debate in national races, and with big backers. In L.A., Sen. Bernie Sanders and former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton endorsed opposing City Council candidates.

“I’ve been watching this stuff out here for 40 years, and when did I see two gigantic political figures on opposite sides of a city council race?” said Raphael J. Sonenshein, a local government expert who runs the Edmund G. “Pat” Brown Institute of Public Affairs at Cal State L.A.

Ben Tulchin, the San Francisco-based Democratic pollster and strategist whom I spoke to for last week’s newsletter, worked for the Sanders campaign. He said Sanders made local endorsements in 2016 — part of his broader strategy to connect with local voters — but it didn’t make a splash until this year. It was the context of those endorsements that mattered.

So why was 2020 different? My sources point to a few reasons.

Get our L.A. Times Politics newsletter

The latest news, analysis and insights from our politics team.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

National goes local

Trump, Trump, Trump

The Trump era was defined by populism, partisanship and high emotion. Earlier this year, Janet Hook wrote about how the Trump and Biden campaigns were seeing unprecedented levels of engagement from voters: high demand for yard signs, skyrocketing levels of small donations, shattered early-voting records.

But the emotions don’t stop when the race is local. Trump has made his feelings about California and its residents abundantly clear, as well as plenty of other recent issues with local stakes, like mask mandates and mail-in voting.

“He’s helped nationalize a lot of things,” Tulchin said. “With politics these days, it’s Trump, Trump, Trump, all the time.”

Voters have changed, too

Across the country, the middle ground between red and blue has grown smaller with each election cycle. And those voters are increasingly tribal in their approach to politics.

My colleague Mark Z. Barabak wrote last month that in 2016 — for the first time since the direct election of U.S. senators in 1914 — every Senate race went the same direction as the presidential race.

Ticket splitting (when voters select candidates of different parties on their ballots) is increasingly rare, even in 2020. According to Five Thirty Eight’s analysis of election results, House Democrats in California performed only slightly better than Biden, by about 2.8 percentage points — suggesting most voters were content to vote for Democrats.

In fact, with the exception of Senate races in Maine, Nebraska and Rhode Island, most states saw little difference between how down-ballot candidates performed compared with their presidential winner.

Voters are also less informed about their neighborhood elections. Local newspapers and small outlets — the kind that cover your school board, for example — have collapsed or consolidated, and the pandemic has only hastened their demise. Meanwhile, national cable news channels like CNN, Fox News and MSNBC have achieved record ratings under Trump.

Elections collide

Over the last half a decade, election officials on the state and local levels sought to improve California’s voter turnout by moving and consolidating smaller elections. They reasoned that voters would be more willing to cast a ballot in, say, a city council race, if they could also vote for bigger offices like governor or president in the same year, or even on the same ballot.

But moving elections in cities like L.A. to even years also made it much easier for voters and campaigns to form connections — or at least the impression of one — between local and national politics. And it probably pulled local races to the left, Sonenshein said.

Those national connections have become important to voters. Endorsements from big, popular figures such as Sanders become “worth their weight in gold,” said Dan Schnur, who teaches political communications at USC and UC Berkeley.

George Floyd’s death alters the landscape

The police killing of George Floyd didn’t happen in California, but it supercharged local elections.

L.A. is home to some of the most influential voices in the national Black Lives Matter movement.

In the weeks after Floyd’s death in May, protests erupted in California cities. Activists heightened scrutiny of police conduct and deaths linked to it, new and old. Calls for accountability targeted not only law enforcement but Hollywood sets, museums and political candidates, just as campaigning was kicking into high gear.

And then there was backlash to the backlash, as voters weighed local measures to alter police funding, and elected officials sought reform — a similar pattern that played out in cities and communities across the United States.

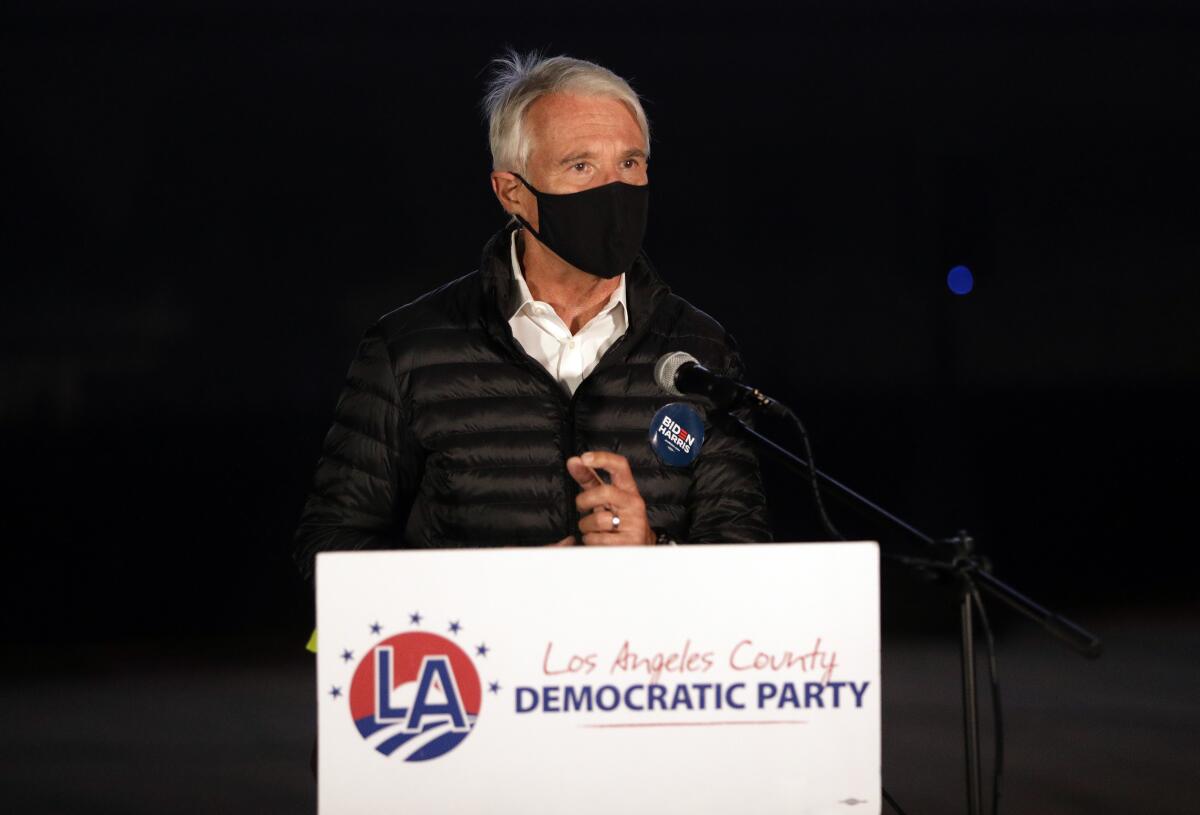

The result was a dramatic shifting of the political landscape in races for offices such as the Los Angeles County district attorney, where progressive candidate George Gascón went from barely surviving his primary to beating incumbent Jackie Lacey.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Let’s talk about that D.A. race

If there was a race to closely examine these competing pressures, it was this one.

It’s local, but it also draws national attention as the largest local prosecutorial office in the country. It was a race between two Democrats — one center-left, one progressive — at a time of party polarization. And the election came at a time of reckoning over policing.

I consulted my colleague James Queally, who writes about crime and policing in Southern California. He spent 2020 closely covering this race and found that even as it took on a national flavor, the politics guiding it retained their local roots.

Our conversation has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

LB: Having closely covered this race, what were your biggest takeaways? Did anything surprise you?

JQ: Given all the unrest this summer surrounding criticism of police force and policing in general, I think the race sometimes got oversimplified to being a referendum on anti-police sentiments. I often talked to people, even prosecutors, who believed Gascón fosters anti-cop sentiments, which is odd given his 30 years spent as a cop. On the other side of things, there were some voters, even some Gascón campaign surrogates, who compared Lacey to President Trump in the waning days of the election. Other than the fact that they both have two eyes and two arms, the D.A. and the soon-to-be-former occupant of the White House have little in common.

Maybe this is the fact that I’m a courts reporter more than a political reporter, but in a race between two supremely qualified candidates with a combined six decades in law enforcement, if I was surprised by anything it was how lowest-common-denominator some of the arguments surrounding the race got to be by the end.

LB: We’ve talked about how the office of Los Angeles County D.A. is unique — it’s kind of a local office, but it has national influence, too. How do you think that positioning affected the race? Has it changed in your time covering it?

JQ: The push to elect more reform-minded prosecutors has been going on for years now, and I think this race gained national attention for a simple and obvious reason: Gascón’s win makes it the largest castle the progressive prosecutor movement has captured.

On top of that, given the office has the power to prosecute officers and deputies involved in fatal shootings in two of the largest police agencies in the state, and that it will be home to some globally watched prosecutions in the coming years (Robert Durst and Harvey Weinstein), I think you’re going to see a lot more national coverage of this office.

LB: You’ve done some reporting on what made Gascón’s campaign successful while Lacey’s fell short. Tell me about some of what you learned. Was it really as ideological as some of those “lowest-common-denominator arguments” made it seem?

JQ: Most of the political consultants seem to think it boiled down to timing.

Once Gascón got to the general, and given what happened over the summer, the race became more about police accountability, and Lacey’s track record on that issue is extremely poor, at least when it comes to fatal use-of-force cases. So, while Gascón was out meeting with the activist groups and younger voters who largely hate Lacey’s guts, she was kind of on the back foot.

Also, in a general election with the president at the top of the ticket, it’s likely the electorate shifted more progressive, tipping in Gascón’s favor.

The view from Washington

— A day after the electoral college formalized Joe Biden’s win in the 2020 election, Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell congratulated Biden as president-elect.

— Biden is expected to pick former South Bend, Ind., Mayor Pete Buttigieg to head the Transportation Department and former Michigan Gov. Jennifer Granholm as Energy secretary, according to people familiar with the plans.

— Biden spoke at a drive-in rally in Georgia for Democratic Senate candidates Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff in a sign of how much the state’s politics have changed.

— Could President Trump have done anything to produce a different election outcome? Maybe. It all leads back to March 18, as Trump weighed how to respond to the pandemic, David Lauter writes.

— U.S. Atty. Gen. William Barr, one of Trump’s staunchest allies, is resigning, write Del Quentin Wilber and Eli Stokols. Trump tweeted the news Monday night.

— Though Trump has championed his Space Force, he has done little to ensure it has the funding, staffing and authority to succeed. When he exits the White House next month, the initiative’s trajectory remains unclear, writes Samantha Masunaga.

— Five years after nearly 200 countries agreed to the Paris Accord — and weeks after one dramatic American exit — French Ambassador to the United States Philippe Etienne spoke to Tracy Wilkinson and Anna M. Phillips about the future of the climate accord.

The view from California

— Is Rep. Katie Porter’s progressive victory in Orange County a sign that liberals don’t need to trim their positions to prevail? Or is Democratic Rep. Harley Rouda’s loss in the district next door evidence that they do? As Mark Z. Barabak writes, it’s a tale of two candidates — and two Democratic factions — and neither side is wholly right or wrong.

— The waiting game continues for Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti, Dakota Smith writes. He was rumored to be a contender for U.S. Secretary of Transportation but that nomination has come and gone and the mayor’s name has yet to be called.

— Meet Suely Saro, the first Cambodian American elected official in Long Beach history. Columnist Frank Shyong writes that the city has hosted the nation’s largest concentration of Cambodian American refugees since the 1980s.

— The Los Angeles Police Department’s largest union is looking to raise at least $10 million to fight the cutbacks and support its favored candidates in 2022, write David Zahniser and Richard Winton.

— Frontline California workers could lose protections if Republican efforts to limit corporate liability are included in a new stimulus package, write Sarah D. Wire and Jie Jenny Zou.

Stay in touch

Keep up with breaking news on our Politics page. And are you following us on Twitter at @latimespolitics?

Did someone forward you this? Sign up here to get Essential Politics in your inbox.

Until next time, send your comments, suggestions and news tips to politics@latimes.com.

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.