Coronavirus Today: A different kind of double jeopardy

- Share via

Good evening. I’m Amina Khan, and it’s Friday, Feb. 5. Here’s the latest on what’s happening with the coronavirus, plus ways to spend your weekend and a look at some of the week’s best stories.

At a time when public officials are practically begging residents to not leave their homes because of COVID-19, the Los Angeles County Superior Court system — the largest in the country — is still requiring people to venture forth for in-person hearings, including eviction proceedings and trials. That’s despite the recent deaths of three court employees from COVID-19, and despite the fact that being in enclosed spaces with other people provides an easy opportunity for the coronavirus to spread.

In traffic courts, scores of people wait in hallways and courtrooms to contest speeding citations, my colleague Matt Hamilton reports. In criminal courts, shackled defendants sit with masks drooping off their faces, and some lawyers remove their masks when addressing a judge. One judge even allowed a witness to testify without a mask.

“Every single day the courts are going through procedures without precautions to keep people safe and holding proceedings that result in people getting kicked out onto the street. It’s a public health disaster,” said Adam Murray, executive director of Inner City Law Center. “If you walk into eviction or traffic courtrooms, you are not seeing wealthy or middle-income people. It’s poor people who have to go in and adjudicate their cases in person.”

Staff and legal groups have pushed for more rigorous methods of screening the public, such as temperature checks. But they haven’t gotten them.

Although lawmakers instituted some eviction moratoriums, which have reduced the flow of eviction cases, such measures typically require tenants to come to court to demonstrate why the moratorium applies. Often, moratorium is a bit of a misnomer, as the measures don’t necessarily stop landlords from filing eviction lawsuits.

These practices pose real exposure risks for Angelenos like Juan Garcia, who rode the bus to a downtown L.A. court to contest an eviction. The disabled widower used a cane as he navigated the Stanley Mosk Courthouse, waited among dozens in a hallway for his hearing, then asked a judge for more time to secure low-income housing — at least another month or two. The judge set an eviction trial for April. “I don’t know what I’m going to do,” Garcia, 60, said outside the courtroom, wrestling with the prospect of homelessness.

L.A. Superior Court has taken steps to significantly reduce foot traffic, and officials estimate 65% fewer people circulate in the system’s 38 courthouses than before the pandemic. Roughly 4,500 people appear remotely each day for hearings. And all of the 600 or so courtrooms across the county have the capability to conduct remote proceedings, said court spokeswoman Ann Donlan.

But many in-person hearings are still taking place, and the criminal courts held nearly 70 jury trials in the final four months of 2020. Sometimes, the parties in a case insist on an in-person hearing. Some litigants lack internet or phone access, or don’t know a remote option is available. And unless a litigant has taken the steps to secure a waiver from the court, each remote appearance comes at a cost: $15 for audio and $23 for video. In eviction cases like Garcia’s, where tenants have just five court days to respond and most tenants lack legal representation, attorneys say that judges often require in-person proceedings, jeopardizing the health of lawyers, clients and court staff.

Court officials say its operations are essential and its services, like providing restraining orders in domestic violence cases and protecting defendants’ due process rights, require keeping courthouses open. But others say many operations can be put off for now. “There is no urgency for a person with a traffic citation to be there now,” said Lauren Zack, an attorney with Public Counsel.

By the numbers

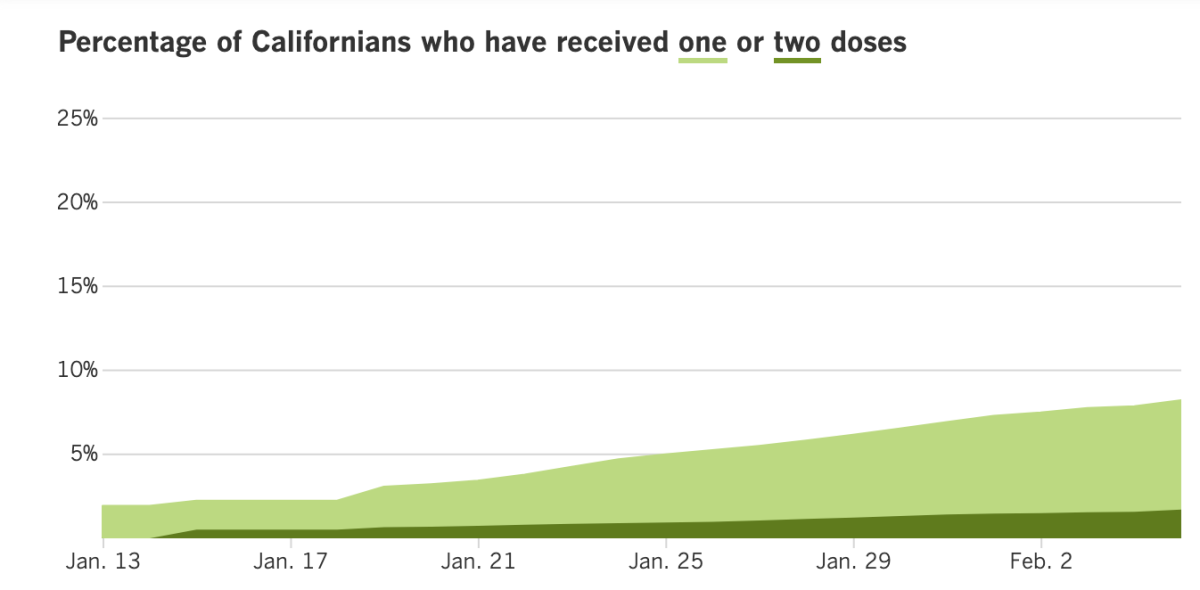

California cases and deaths as of 6:11 p.m. PT Friday:

Track California’s coronavirus spread and vaccination efforts — including the latest numbers and how they break down — with our graphics.

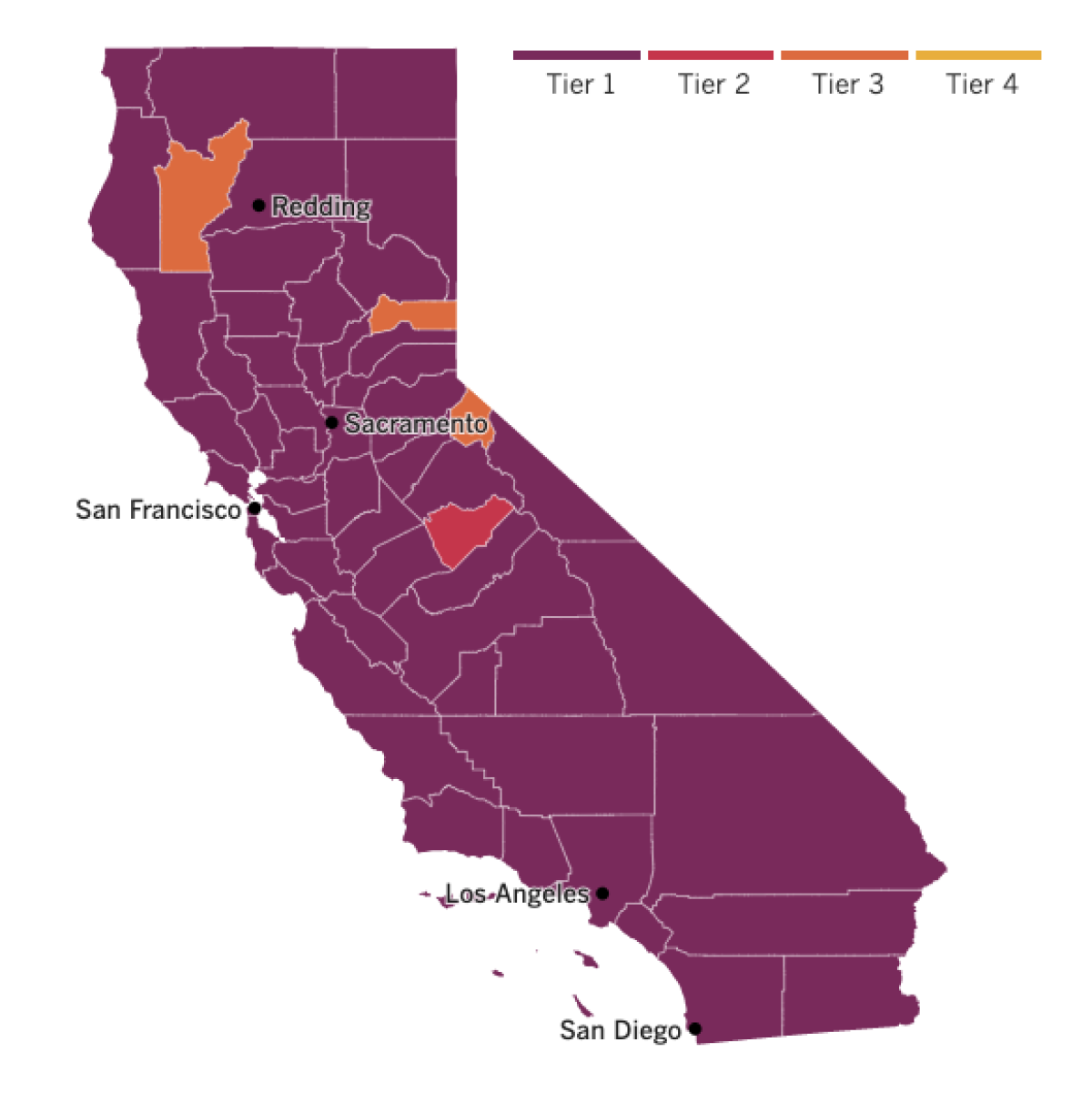

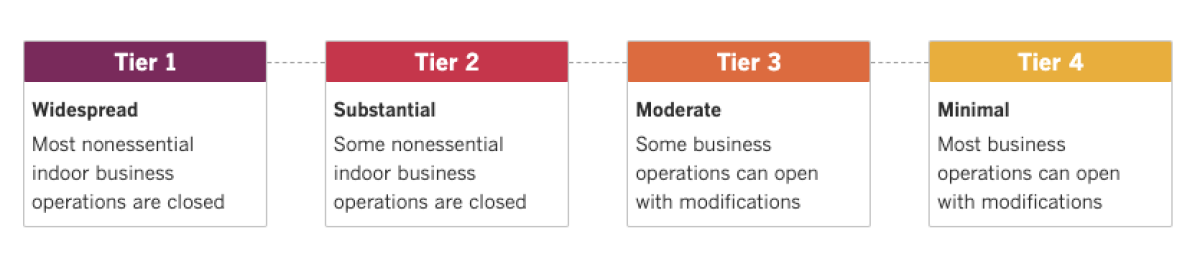

See the current status of California’s reopening, county by county, with our tracker.

What to read this weekend

“That’s how we found out he was a legend”

For over three decades, Hashem Ahmad Alshilleh helped to bury Southern Californian Muslims. He washed and shrouded the corpses of men per Islamic tradition and drove the bodies of men and women to cemeteries from Rosamond to Victorville to San Diego. The slight but strong truck driver from Riverside stayed with each body until it was lowered into the ground so he could ensure the deceased lay on his or her right side, facing toward Mecca.

Now, his own grave lies one plot over from the last person he buried.

Alshilleh died of COVID-19 — a disease that was killing so many Muslims by the fall that he would leave home at 4 a.m. and often wouldn’t return until 9 p.m. He never charged for his services, relying only on donations. Sometimes he’d pool those funds to pay for the funerals of strangers, Muslims and not. “He never called it work,” his daughter Ayah Shilleh-Velazquez said. “He never did it as a source of income. He would always tell us the same thing: ‘I’m not doing it for money. I do it for God.’”

His five children — two police officers, two construction contractors and a nurse — were aware their father was an integral part of the local Muslim community. But it wasn’t until he passed away Jan. 8 at 75 that they learned of the depth and breadth of his impact. “We knew he was a great guy, but talking to people, that’s how we found out he was a legend,” said his oldest son, 33-year-old Ahmad. Read columnist Gustavo Arellano’s story of this remarkable Southern Californian.

Who helps the helpers?

During the pandemic, with the families of critically ill patients barred from entering hospitals to minimize the virus’s spread, healthcare workers have become conduits for the anguish of patients and their loved ones. They field hundreds of phone calls a day from anxious relatives. They monitor their cellphones and reply to text messages. They pray for their recovery, even when they may know the odds aren’t on a patient’s side.

Dr. Christine Choi, a tough, upbeat second-year resident at Harbor-UCLA Medical Center, had to facilitate a family’s final moments with their loved one over FaceTime. “The sound of the family members crying,” Choi said, “I probably will never forget that.”

Even before COVID-19, nurses and doctors were already prone to high rates of depression and suicide, experts say. The pandemic has introduced new fears of contracting the virus and bringing it home to their families, repeated exposure to death, and an unprecedented number of very ill patients that can make healthcare workers feel helpless, my colleague Soumya Karlamangla writes.

Being near so much pain will likely take a grave toll on medical workers’ mental health, experts say. Many worry that doctors and nurses will burn out or retire early and that the experience, unprecedented in length and scope, will trigger high rates of anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder that will far outlast the pandemic.

They’ll do what it takes to smell again

Smell is instrumental in our perception of flavors, allowing us to distinguish between oranges and lemons and warning us when food is spoiled. It keeps us safe, allowing us to detect smoke from a fire or gas from a leak. And it’s tied to our memories, transporting us back to a person or place we love.

It’s also one the first things to go for many patients with COVID-19. Though most recover their senses within weeks, an estimated 10% suffer long-term smell dysfunction, my colleague Brittny Mejia writes. And some of them are going to great lengths to get their sense of smell back.

Take Mariana Castro-Salzman, a 32-year-old in Los Angeles whose senses of smell and taste are still scrambled nearly a year after recovering. Onions and garlic trigger nausea. Coffee smells like a burned tire, but worse. Because of the distorted smells, a condition known as parosmia, she has endured headaches, lost weight and repeatedly broken down in tears. “It’s like a mind game, because you remember all the smells and tastes, but then the second you put it in your mouth it’s nothing like it used to be,” she said. “It’s like a completely different experience.”

People dealing with smell dysfunction have scheduled medical appointments with all manner of specialists, joined support groups and spent months using smell kits to retrain their noses and brains. Universities have launched studies on recovering smell after COVID-19, starting treatment trials using nasal rinses and essential oils. Check out this story to see how the pandemic has turned olfaction restoration into a booming business.

“A crucible of riotous viral mutation”

At this point in the pandemic, you’ve probably heard that there’s a crucial reason to stop the virus from spreading: The more people it infects, the more opportunity there is for dangerous mutations to arise. But they’re also likely to emerge in the bodies of “long haulers” — patients who battle the virus for months, often because they have weakened immune systems.

Researchers got a worrisome window into this process through the body of a 45-year-old man in Boston who was sick for 154 days, one of the longest COVID-19 illnesses on record. Over that time, this man’s body “became a crucible of riotous viral mutation,” my colleague Melissa Healy writes. “He offered the world one of the first sightings of a key mutation in the virus’ spike protein that set off alarm bells when it was later found in strains in the United Kingdom, South Africa and Brazil.”

Among the viral mutations in his body was a change known as N501Y. This mutation appears in the U.K. strain of the virus, where it’s thought to help make the virus more transmissible. In a strain from South Africa, it may reduce the effectiveness of vaccines and treatments. The Boston patient is now being seen as a key harbinger of the coronavirus’s ability to spin off new and more dangerous versions of itself. He died over the summer, but his medical file is still helping researchers understand and even anticipate the emergence of new strains. Read what other coronavirus secrets scientists learned from this strange case.

The best of hard options

One of the dangerous ripple effects of the surge in COVID-19 hospitalizations has been the delaying of elective and nonemergency surgeries. It may not sound as urgent as the influx of critically ill COVID-19 patients, but it has already left its mark on many vulnerable Californians, my colleague Marisa Gerber reports.

Take Miguel Rangel of San Fernando, who has chronic kidney disease, lives with constant pain and for a decade has gotten dialysis nightly via a catheter into his abdomen. The 43-year-old electrician was scheduled to have a parathyroid gland removal in mid-December to help alleviate his severe bone pain and improve his quality of life. But after the procedure was postponed due to an infection, the hospital said to expect delays in getting back on the surgery schedule. “Because of COVID,” they told him.

These kinds of postponements are a way to conserve critical resources, such as ventilators and oxygen, and to free up doctors and nurses. But deciding whether a procedure is truly elective and how long it can be pushed back without causing harm always involves a certain level of subjectivity. And postponements, no matter the cause, often translate into stressful and scary delays for patients, particularly those with underlying health conditions. There’s also a risk that delays can exacerbate racial and socioeconomic inequities.

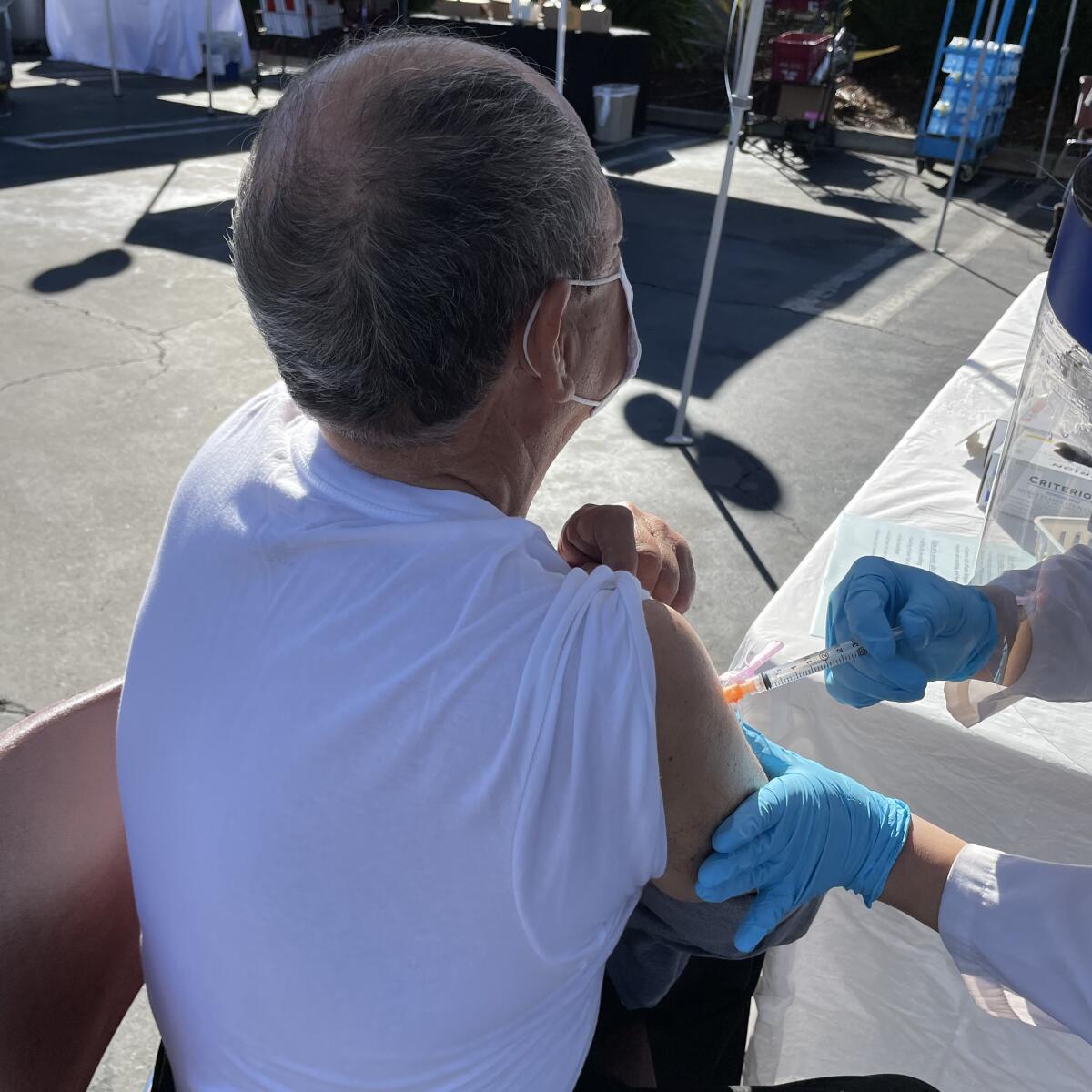

If this guy could get his COVID-19 shot, so can you

As Lorenzo Arellano stood in line for the first dose of his Moderna vaccine recently, his son Gustavo considered it no small miracle. That’s because his dad, while not a full-on pandejo (the Mexican version of a covidiot), did a pretty good job of sounding like one sometimes. “He has alternately claimed the coronavirus didn’t exist, was all hype, was a government conspiracy, or had already infected everyone, so caution was pointless,” our columnist writes.

Part of the problem was that early on, his dad didn’t personally know anyone who had contracted the virus. “The other issue, frankly, is that he’s a stubborn country macho who sees the world and all its maladies as something to dominate and not be afraid of,” Gustavo Arellano writes. “Toxic masculinity is a hell of a preexisting condition to have during a pandemic. Too many of us, Latinos and not, have had to deal with it, to the point of broken friendships and strained familial ties.”

But Gustavo did manage to get through to his beloved dad — at least, enough that he showed up for his vaccine appointment. And his dad had a message for his son’s readers: “Tell everyone Doubting Lorenzo — stubborn, country, macho — took the vaccine because he loves his family,” he said. “He took it for his children, grandson, and viejita mom, who’s very strong. And if Doubting Lorenzo took it, then no one has an excuse.” Read on to find out how the family brought him around.

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most.

What to do this weekend

Get outside. Enter the lottery for a permit to hike Mt. Whitney, the highest peak in the lower 48 states and a popular goal for hikers who want to challenge themselves. (Prerequisites: physical conditioning, stamina and a U.S. Forest Service permit.) Or snap some photos of plants and wildlife during a bioblitz at Earvin “Magic” Johnson Park, a 120-acre, recently renovated site in Willowbrook. It’s on now through March 31 — here’s how to get started. Subscribe to The Wild for more on the outdoors.

Go for a drive. Head out to Yosemite National Park, where you might catch a glimpse of Horsetail Fall’s famed “firefall” (be sure to book a day-use reservation). Or take a trip to the 1970s with this architectural driving tour of L.A., which takes you past the Westin Bonaventure Hotel, the Triforium and the Brady Bunch House. Subscribe to Escapes for more ideas.

Watch something great. Our weekend culture watch list includes an L.A. Phil virtual fundraiser featuring Julie Andrews, Natalie Portman, Katy Perry and Common, among others. And in his Indie Focus newsletter’s roundup of new movies, Mark Olsen highlights “Malcolm & Marie,” starring John David Washington and Zendaya as a couple having an extended argument after a night out.

Eat something great. Planning on making yourself some Super Bowl-worthy snack fare? Check out this recipe for game-day nachos. And speaking of game day, here are some tips on how to watch the big game without spreading COVID-19. (Hint: virtual parties are probably the way to go this year.) Subscribe to our Cooking newsletter for more great recipes.

Go online. Here’s The Times’ guide to the internet for when you’re looking for information on self-care, feel like learning something new or interesting, or want to expand your entertainment horizons.

The pandemic in pictures

Throughout the pandemic, many parents have formed pods to give their kids the educational and social peer support they needed. Some have worked out great; others either failed spectacularly or didn’t turn out as expected. Two Southland families decided to go one step further and hunker down in a house together, riding out the pandemic with four parents, six kids and two dogs all under one roof.

Because the Knights and the Levinsons were both following strict COVID-19 protocols and had not even been to a grocery store since March 9, they felt comfortable seeing one another without risk of infection. So after months of tumult, the couples agreed to end their leases, pool their resources and move in together for a year.

All families must compromise and choose their battles, but not all have to do so with another family present 24/7, my colleague Lisa Boone writes. Remarkably, no conflicts about bills or money, or household chores, which the two families split, have arisen.

I should note that not all of us can afford a $6,200-a-month McMansion in Orange County — you can certainly cross me off that list — but it’s a fun look at what a less lonely, more communal pandemic life could look like.

Resources

Need a vaccine? Keep in mind that supplies are limited, and getting one can be a challenge. Sign up for email updates, check your eligibility and, if you’re eligible, make an appointment where you live: City of Los Angeles | Los Angeles County | Kern County | Orange County | Riverside County | San Bernardino County | San Diego County | San Luis Obispo County | Santa Barbara County | Ventura County

Practice social distancing using these tips, and wear a mask or two.

Watch for symptoms such as fever, cough, shortness of breath, chills, shaking with chills, muscle pain, headache, sore throat and loss of taste or smell. Here’s what to look for and when.

Need to get tested? Here’s where you can in L.A. County and around California.

Americans are hurting in many ways. We have advice for helping kids cope, resources for people experiencing domestic abuse and a newsletter to help you make ends meet.

For our most up-to-date coverage, visit our homepage and our Health section, get our breaking news alerts, and follow us on Twitter and Instagram.