- Share via

Second in a series exploring the origin stories of three of the Chargers’ top defensive players with Florida roots.

Today, edge rusher Khalil Mack, whose harmony at home helped shape him as a player — and a man.

FORT PIERCE, Fla. — He could see the potential in all that mass and all those muscles, the physical promises so pronounced that the kid’s high school coach begged his father to let him play.

Robert Wimberly knew Khalil Mack could fit in at Liberty University right away and maybe, if things went well, with two more years of development be ready for a larger football program.

Then a Liberty assistant, Wimberly was the only college coach who showed interest in Mack, a prospect left on the periphery because of a high school career that covered a single season.

The staff at Florida said Mack couldn’t play in the Southeastern Conference. Miami’s coaches expressed similar doubts about his Atlantic Coast Conference chances. Others questioned whether Mack was explosive enough or flexible enough.

A sport that values so highly what it can see on tape lacked sufficient evidence — just 12 games? — on Mack.

But Wimberly had seen enough of his 140 stops during that one fall at Westwood High to appreciate that, as a linebacker, he played with something all defensive coaches believe they can build upon: a solid base.

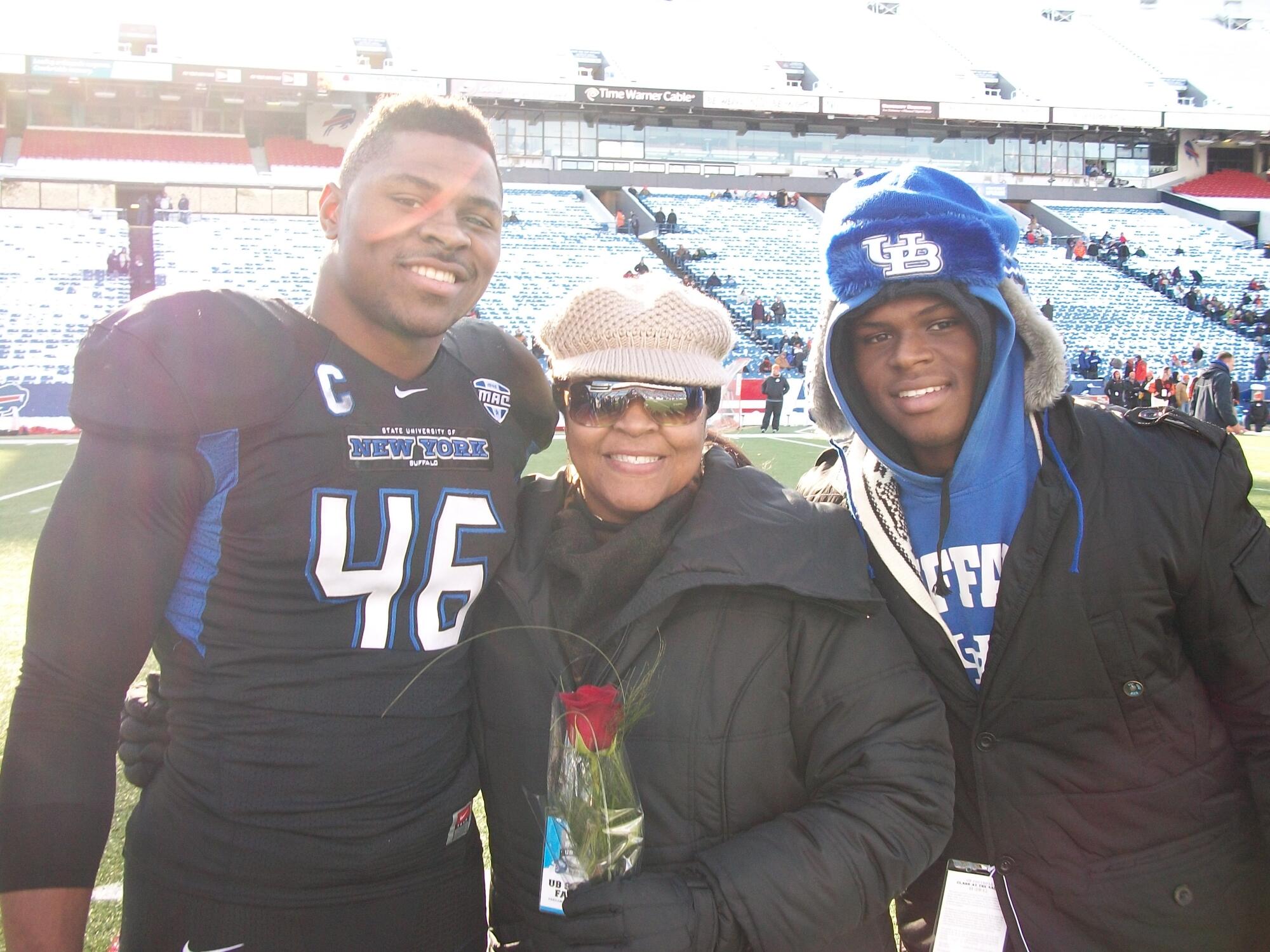

What Wimberly didn’t realize until he sat down with Mack one night for dinner — along with Mack’s parents and two brothers — was how impressive the kid’s foundation was, as well.

Years before standout NFL cornerback J.C. Jackson signed with the Chargers, his life in a small Florida town was nearly derailed by armed robbery charges.

“It was almost like the Huxtables, you know, on the ‘The Cosby Show,’ ” Wimberly recalled. “There was sincere love among them. Everyone was genuinely excited for Khalil. Just a lot of love and respect in that household.”

When the Chargers aimed to rebuild their defense this offseason, the first move was to trade for Mack, who came from Chicago in mid-March at the cost of two draft picks — a second-round selection in 2022 and a sixth-round selection in 2023.

With Mack now 31 and trying to rebound from a season in which he missed 10 games because of a foot injury, it is fair to wonder where the six-time Pro Bowl pick is heading.

But there can be no questioning where Mack came from, a former two-star recruit reared in a five-star home that as recently as last year gained even more glow.

“It’s just all the grace of God,” Mack’s father, Sandy, said. “This couldn’t be orchestrated. You couldn’t write this. We don’t take any credit for what God has done. That would be robbery.”

The name “Khalil” came from one of Sandy’s muscle magazines and proved prophetic when the baby boy debuted at nearly 11 pounds and with definition in his arms, legs and everywhere else.

This was a toddler with traps. Doctors were so concerned about Mack’s size that they had him tested for diabetes.

“He came out with quads,” Sandy said. “Big shoulders. Big legs. Right away I thought, ‘This boy’s different.’ ”

Sandy and his wife, Yolanda, were high school sweethearts at Fort Pierce’s Central High. They were married in the cafeteria of another school nearby, Lincoln Park Academy, where Yolanda’s mother worked.

Having lost his father at an early age, Sandy never had the chance to play high school sports despite his own muscular, athletic frame. He and twin brother Sammie Jr. had to work instead.

“Mom told us,” Sandy explained, “ ‘You can either play sports or you can eat.’ ”

As an adult, he became a corrections officer at the St. Lucie County Jail, and, concerned with protecting himself, Sandy began working out at a local gym. He and Sammie Jr. soon were battling to see who could get bigger.

That’s the way it was with these twins, who competed against each other with the intensity of worst enemies or best friends.

And that’s also how it was for Sandy’s three sons — Sandy Jr., Khalil and Ledarius. As the oldest brother, Sandy Jr. loved challenging Khalil, the quietest of the Mack boys. So did Dad.

Years later and still today, observers marvel at Mack’s ability to go from talking soft to hitting hard in the time it takes to stride across the white lines that define a football field.

“Between Sandy Jr. and I, we used to put it on him pretty good,” Sandy, 57, said. “Khalil got it from both of us. You better throw a switch in that situation because crying’s not going to work.”

‘The first guy you hit out there, I don’t want him to get up.’ That was my little pep talk.”

— Sandy Mack, on the instructions he gave Khalil Mack before his first youth football game

He took it, but Mack also gave it back. Sandy recalled more than once having to halt a backyard basketball game to remind Mack that Dad had to go to work in the morning and he’d prefer to do so without multiple bruises.

Yolanda’s half of the family is where the quiet comes from. Mack loved spending time with his maternal grandfather, Alfred Booker, the two bonding after Booker would pick him up from school.

“He has a personality like my dad — real laid back, no worries,” Yolanda said. “Khalil is just Khalil, you know. He was kind of a homebody.”

“Boring and focused” is how Mack has described himself when he was growing up, those qualities leading some people around the family to question his toughness. The doubters included a cousin who used to call Mack “soft.”

The fact he wasn’t especially drawn to football added to the notion that a kid who would become a three-time NFL All-Pro and quarterback terrorizer somehow lacked sufficient aggression.

“He just never really wanted to play the sport,” Sandy said. “But I’d tell people all the time, ‘If I get him off this leash, you’ll see.’ ”

Joey Bosa says new Chargers teammate Khalil Mack is a much different pass rusher than he, which should be an advantage when they rush into the regular season.

When he was 12, Mack decided to give organized football a shot. First, though, he and his father had a discussion.

“I sat him down and told him, ‘OK, these guys are saying you’re soft,’ ” Sandy remembered. “ ‘The first guy you hit out there, I don’t want him to get up.’ That was my little pep talk.”

To understand how things went from there, it’s not inaccurate to report that Mack put the pop in Pop Warner. Early in his first game, Sandy recalled, Mack caused a violent collision near the sidelines after appearing only as a blur.

“I didn’t even know it was Khalil,” Sandy said. “People were saying, ‘Mack, that’s your son!’ I was like, ‘Yeah!’ While I was celebrating, I didn’t see the paramedics coming to get the other guy. I didn’t know Khalil was going to do it for real. The kid had to go to the hospital. I felt kind of guilty about that.”

Still, Mack, more interested in basketball, wouldn’t play football again until late in high school, during the spring before his senior year. By then, a torn patella tendon had sidetracked his hoops plans and, while rehabbing from the injury, Mack had thrown himself into weight lifting, first asking to join his father at the gym and later insisting on it.

At the time, Sandy had concerns about his son’s academic standing, particularly Mack‘s struggles with math. Admitting he hadn’t been a great student, Sandy said he understood the difficulties in falling behind in school.

The Rams open training camp as the defending Super Bowl champions, but there are plenty of questions surrounding the team at the start.

Sandy also had worked at a juvenile detention center and was aware of the dangers that lurked for teenagers, especially outside a structured life. He figured the military might be Khalil’s best chance to get out of Fort Pierce.

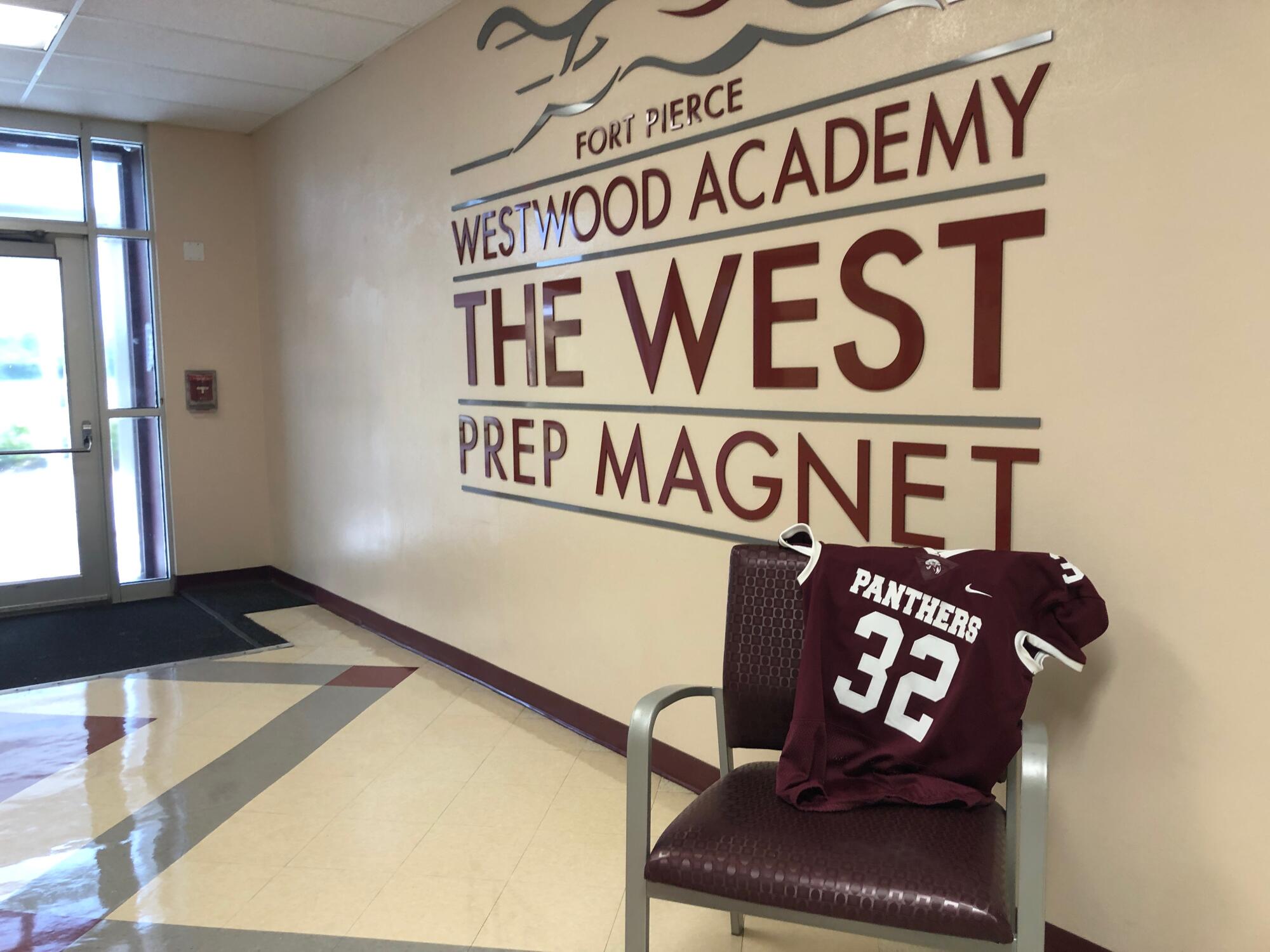

But one day at work, Sandy’s phone rang and it was Westwood High’s new coach, a man named Waides Ashmon, who had just pulled Mack out of class to talk to him about playing football again. Mack’s response: “You need to talk to my dad.”

“I called and said, ‘Mr. Mack, I’ve been doing this a long time,’ ” Ashmon said. “ ‘I’ve never guaranteed a parent that their kid’s gonna go to school. But if you allow Khalil to play for me, I promise you he’ll go to school free.’ ”

Ashmon was so certain of Mack’s potential that he made the assurance even after glimpsing Mack only in a collared shirt and shorts. He figured that physique alone would be too enticing to college coaches.

The conversation — and enclosed guarantee of a continued, free education — convinced Sandy, who agreed by the end of the call to allow his son to return to football.

With that decision, Mack went into full pursuit, this player who later would become famous for his ability to chase down quarterbacks.

In one of his first practices that spring, Mack proved he could do more than just look as if he belonged. With Yolanda waiting in the parking lot to take her son to a class at a nearby community college, Westwood’s coaches told Mack to go first during a tackling drill.

“Khalil beat the block and smacked the running back and it was like, ‘Oh, you’re done. Go to class, kid,’ ” said Jabari Williams, then a Westwood assistant. “It took just one hit. After that, we knew we had ourselves something.”

Yet, Mack was regarded as only the third-best prospect on a team that would finish 10-2. Defensive lineman Luther Robinson, who went to Miami and eventually to the Green Bay Packers, and quarterback Isaac Virgin, who played at South Florida as a tight end, were ranked ahead of him.

As much as the Westwood staff promoted Mack — Williams: “We were begging schools to take him.” — the pleas went unheard.

“I was like, ‘What are y’all … we can’t be watching the same film,’ ” Ashmon said. “But I also knew Khalil’s work ethic and how with college coaching he would get a lot better.”

Mack’s lone offer came from Liberty, which is where he was headed until Wimberly left to take a job at Buffalo. Mack followed him, receiving the full-ride Ashmon had promised Sandy.

Chargers coach Brandon Staley is a massive tennis fan, and in particular a devout Rafael Nadal fan. He and wife Amy went to Wimbledon for first time.

That summer and into training camp, Wimberly remembers the Bulls’ coaches debating about whether to play Mack or redshirt him. Asked his opinion, Wimberly sided with redshirting, noting that Mack, with more experience, could be “super special.”

Buffalo did redshirt him, slowing the start of Mack’s college career but hardly the beginning of his rapid growth. Actually playing wasn’t a requirement to show he could make plays.

One day, a reporter from upstate New York called Sandy with a question:

“Mr. Mack, do you know what your son is up here doing?”

“No. No I don’t.”

“Your son’s doing some things we’ve never seen before.”

“Really?”

“Mr. Mack, I think your son is going to be something real special here at Buffalo.”

Wrecking practices, that’s what Mack was doing, to the point where Wimberly said he was asked more than once by a fellow Buffalo assistant, “Wimbo, can you talk to him, please?”

Mack was leaving impressions — the black-and-blue kind, and others much more permanent.

Sandy took another call from Buffalo one afternoon. This time, it was an assistant coach telling him his son was doing something the coach had never seen before: Mack was cleaning the locker room.

When his boys were young, Sandy would bring them along anytime he would do volunteer work in and around Fort Pierce. “Because it’s just the right thing to do,” he said he’d tell them if they asked why they had to go.

Today, Mack is widely recognized for giving back. His foundation made a $500,000 donation to a Fort Pierce park that now includes a football field bearing Mack’s name.

Westwood needed football uniforms a few years back and, the school’s athletic director said, Sandy wrote a $20,000 check. Just a couple weeks ago, a box full of several pairs of cleats showed up unannounced at Westwood, compliments of Mack, who also has done things such as pay off all the layaway bills at the local Walmart around Christmastime.

“It’s a family thing,” Ashmon said. “Khalil’s mimicking his dad. His dad was giving back way before Khalil became Khalil.”

After he signed his first NFL contract, Mack bought his parents a home in nearby Vero Beach. He also paid off his dad’s truck.

The BMW and Mercedes in the driveway of that Vero Beach house came from Mack, who has rewarded some of the younger members of the extended household with cars in exchange for maintaining their grades.

This is a family anchored in its faith and its church, Sandy and Yolanda both deacons at the Miracle Prayer Temple Worship Center. They all love music and have been part of the church band. Sandy has written and recorded gospel songs.

Mack can sing, too, and also taught himself to play the guitar while in college. Sandy thought he was the best piano player in the family until Ledarius came along.

As the church’s music director, Sandy would arrange songs so that the Macks could sing four-part harmony. They still can do it, on cue, which happened recently when the boys were back together.

“I’m telling you, you couldn’t orchestrate this. No way. This was orchestrated at a higher level.”

— Sandy Mack, on discovering he had another son who played in the NFL

So, when that Buffalo assistant called with the news that Mack was picking up his teammates’ trash, Sandy said the words came wrapped in reassurance.

“That made me feel like, ‘Wow, he got it,’ ” Sandy said. “For me to get a call from somebody way up in Buffalo to tell me that made me think Khalil’s going to be OK.”

OK, plus plenty more. With the Bulls, Mack would develop into a freakish force — one capable of lifting offensive linemen off the ground one-handed — and easily the greatest player in program history.

As a senior, he had 2½ sacks, nine tackles and an interception for touchdown against Ohio State in the game that cemented Mack’s status as an NFL prospect and a Bulls legend.

“Buffalo plays in the MAC,” Sandy said. “It can’t be coincidence that that happened. I told him, ‘Khalil, they’re spelling Mack wrong. Make sure they know how to spell Mack before you leave.’ And that’s what he did.”

(Five years after Khalil left Buffalo, Ledarius joined the Bulls’ football program for two seasons. He debuted in the NFL last year, appearing in three games for the Bears. How rich is the athletic DNA in this family? Ledarius attended a high school — Lincoln Park Academy — that didn’t have a football team and then went to a small college in Miami to play basketball before giving football a try.)

The story goes that in the lead-up to that 2013 season opener in Columbus, then-Buckeyes coach Urban Meyer was talking about Mack when, suddenly forgetting his name, referred to him as “No. 46.”

After Ohio State’s 40-20 victory, Mack approached Meyer, extended his right hand and introduced himself.

Longtime coach Lou Tepper was Buffalo’s defensive coordinator during that time. He spent nearly a half-century in football and literally wrote the book on linebacker play, putting Mack on the cover of the second edition of “Complete Linebacking.”

To grasp the totality of Mack’s impact, though, consider that Tepper, to this day, texts Mack a Bible verse every Saturday morning and speaks of him with a reverence rooted in nothing having to do with football.

“I love him,” Tepper said, “and if he had never played a down in the NFL, if he had never been drafted, I wouldn’t love him any differently.”

So what’s left? Just this: Remember that line about the five-star home gaining more glow? In June of 2021, Sandy and Yolanda heard from a man named Jalen Parmele, who, using one of those ancestry programs, discovered he was a Mack boy, as well. The original Mack boy.

Sandy and Yolanda had a son before Sandy Jr. arrived. At the time, they both thought they were too young to properly handle the responsibility, so they put the baby up for adoption.

Parmele grew up in Michigan to be a football player and made the NFL, a running back who spent parts of five seasons with Baltimore, Jacksonville and Arizona.

A month after Parmele reached out to the Macks, everyone reunited in Florida for a genuine Son-shine State celebration. They filled in the gaps of their life stories and shot selfies, embracing a previously unknown family chapter.

Sandy smiled when he pointed out that Parmele played in college at Toledo, which is in the same conference as Buffalo. That’s right, another Mack in the MAC.

“I’m telling you, you couldn’t orchestrate this,” Sandy said. “No way. This was orchestrated at a higher level.”

More to Read

About this series

There were stops in Lakeland, Auburndale, Immokalee, Fort Pierce, Vero Beach, Haines City and Davenport.

All in the name of exploring the roots of three of the Chargers’ top defenders — cornerback J.C. Jackson, edge rusher Khalil Mack and safety Derwin James Jr.

Each a small-town legend from a rural Florida outpost before now joining forces some 2,500 miles from home in the intense glare of the NFL.

Along with edge rusher Joey Bosa and cornerback Asante Samuel Jr., both of whom attended St. Thomas Aquinas in Fort Lauderdale, the Chargers’ 2022 defense is, as James smartly noted this spring, “Florida’d out.”

So, presented in three parts over three days, here are the origin stories of Jackson, Mack and James, told largely through the eyes of the parents who raised them.

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.