Settlement would end NFL concussion suit

- Share via

In an unexpected acknowledgment of the medical damage sustained by professional football players, the National Football League on Thursday reached a tentative settlement to provide $765 million in medical and other benefits to former players suffering from concussion-related brain injuries.

The settlement of a lawsuit brought by 4,500 former players allows the league to avoid years of litigation and the potential for billions of dollars in damages. Current players are not covered by the agreement, which awaits approval by a federal judge.

The league still faces a major challenge in making the game safer. Despite rule changes designed to reduce head injuries, collisions have been growing more violent and concussions remain a significant danger.

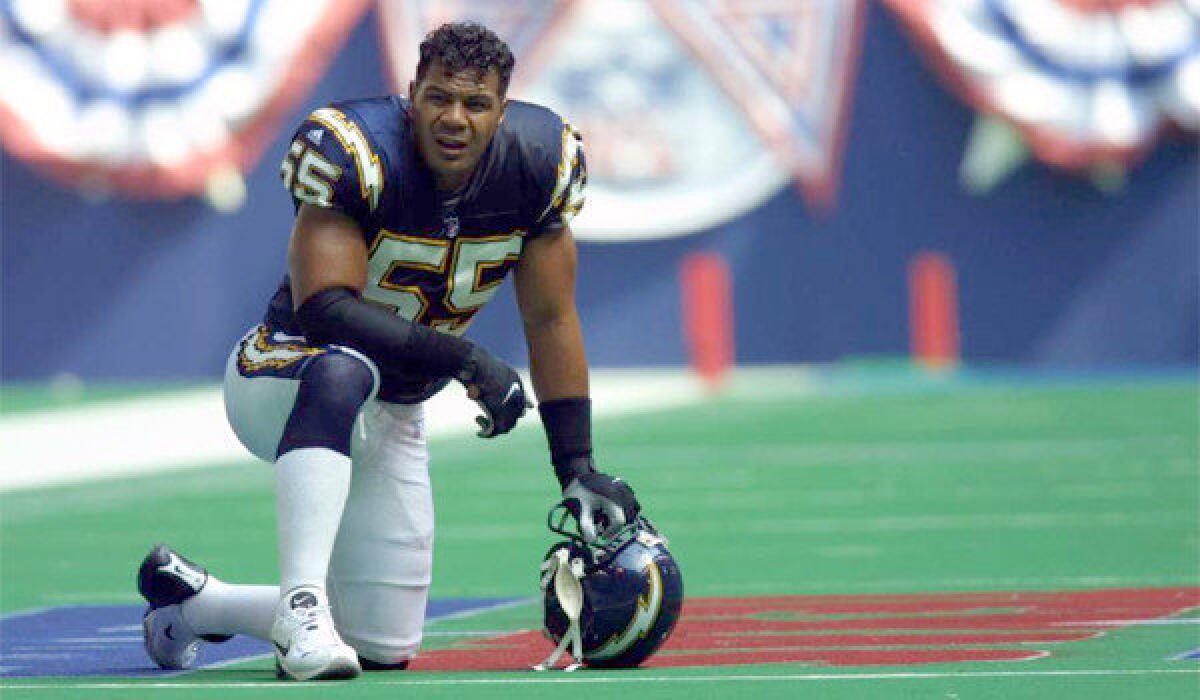

“My only concern from the very start was they just needed to make the game safer,” said Gary Plummer, a former linebacker for the San Diego Chargers and San Francisco 49ers who was among the players suing the league. “We have generations of kids to come who are going to be playing football. I’ve suffered the effects of concussions dramatically in the last few years and it’s only gotten worse.”

Plummer says he has suffered severe headaches and memory loss that he believes were caused by multiple low-grade concussions that he experienced in almost every game during his career.

The agreement resolves a consolidated lawsuit by former players who claimed the NFL concealed the long-term danger of concussions. The case was first filed in Philadelphia in 2011, and the accord was reached early Thursday after nearly two months of intensive negotiations.

The money is to be paid over 20 years and will be used for medical examinations, research, and to compensate players or their families. Individual payouts could be as high as $5 million for players with Alzheimer’s disease, $4 million for the families of deceased players found to have a concussion-related brain disease called chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, and $3 million for other cases of dementia. The settlement will also fund safety and medical research programs.

The settlement resolves one aspect of the legal problems. In a separate arena, the NFL is pushing legislation in Sacramento that would further reduce its responsibility to cover players’ injuries. The state Senate is expected to vote in the next few days on legislation to make it more difficult to file workers’ compensation claims in California.

Retired football, basketball, baseball, hockey and soccer players around the nation have filed thousands of claims for years seeking monetary awards and medical care for injuries suffered on the field. The state is alone in allowing claims to be filed years after an injury occurs. The law covers athletes who competed in California — not just those who played for state teams.

Under terms of the bill, which has passed in the Assembly, athletes who did not play for California teams would not be allowed to file claims in the state.

Thursday’s settlement entitles all former NFL players to seek medical treatment and compensation. They will receive varying amounts based on their condition and the number of years they played in the league.

“Glad to see the older guys are getting taken care of with the concussion settlement,” said Raiders punter Chris Kluwe over Twitter. “It’ll never be enough, but it’s a start. Curious, though, what the NFL is going to do after putting $765 million into figuring out you can’t pad the inside of someone’s head.”

Several players in recent years have been diagnosed with CTE after their deaths, among them suicide victims Junior Seau, a longtime San Diego Charger, Dave Duerson and Ray Easterling. Their families and others in similar situations are eligible for seven-figure compensation from the league, said lead plaintiffs’ lawyer Christopher Seeger.

Seeger said the settlement “will provide immediate compensation to severely injured retired players that need the help today, not 10 years from now through litigation, or 20 years from now, but today. And it will provide baseline assessment and medical benefits to those who are symptom-free, or beginning to show the early signs of a neuro-cognitive problem.”

“This agreement lets us help those who need it most and continue our work to make the game safer for current and future players,” said Jeff Pash, an NFL executive vice president and the league’s top lawyer. “Commissioner [Roger] Goodell and every owner gave the legal team the same direction: do the right thing for the game and for the men who played it.”

Under the settlement, the NFL does not acknowledge that the retired players’ injuries were caused by football, said former U.S. District Judge Layn Phillips, the court-appointed mediator who brokered the proposed settlement.

Although evidence of a link between concussion and long-term cognitive and psychiatric consequences is mounting, it may take many more studies to clarify the relationship, experts say.

Among scientists, there is universal agreement that concussions are as much a consequence of playing football as are wrecked knees, blown-out shoulders, and bad backs. But in the immediate wake of a blow to the head, proof of traumatic brain injury can be elusive unless there is evidence of bleeding or swelling of the brain.

CT and MRI scans can’t detect the massive disturbances that affect the brain after a trauma. Nor can they measure damage to the “white matter” that carries electrical impulses across the hemispheres of the brain and from region to region. Yet research suggests both of those processes may be key to concussion’s most damaging consequences.

Even when radiologic imaging does suggest brain injury, many players don’t suffer the headaches, fatigue and loss of memory and concentration that signal the brain has been hurt. Others who come up clean on a CT scan may complain of subtle symptoms for weeks or months after a big hit.

A concussion diagnosis can be hard to make even when a player is rushed from the field to a hospital — though that response is rarely taken in a sport in which athletes in the past have often been urged to “walk it off” and get back in the game. When depression, dementia, concentration difficulties and tremors appear years — sometimes decades — after a player has retired, any link between those symptoms and past blows to the head is extremely difficult to prove.

Former NFL running back Kevin Turner, who suffers from amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or Lou Gehrig’s disease, said the settlement “will lift a huge burden off the men who are suffering.”

“Chances are, I’m 44 now, I won’t make it to 50 or 60,” said Turner, who apologized for his inability to speak as clearly as he once did. “I have money now to put back for my children to go to college, and for a little something to be there financially.”

Times staff writer Ken Bensinger contributed to this report.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.