1968: Dodgers relent as players find power to precipitate change

- Share via

For a century, professional baseball players were regarded as entertainers: see ball, hit ball, play in whatever city you are assigned, for whatever salary you are assigned, and keep your mouth shut.

In 1968, as Americans rose to let their voices be heard, so did the ostensibly privileged subset of baseball players.

They negotiated the first collective bargaining contract in professional sports history, under which the minimum salary rose from $6,000 to $10,000, and the weekly spring training stipend was increased for the first time in 21 years. The next year, Curt Flood refused to accept a trade, the first step toward the adoption of free agency.

To this day, baseball players remain among the least likely athletes to speak up on social issues rather than economic ones, with no prominent player shouting for civil rights from the platform that LeBron James occupies today, or Muhammad Ali did in 1968.

However, the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. 50 years ago embroiled the Dodgers in a controversy beyond the sports pages. During a time of national mourning, a nucleus of major league players made what was then considered a revolutionary assertion: The games could not go on without them.

At Dodger Stadium, despite an original plan to the contrary, the game did not go on.

King was killed April 4, four days before the first scheduled games of the 1968 regular season. Out of respect, or out of concern for public safety given the unrest that followed in Los Angeles and elsewhere, the openers were indeed postponed — but not without clumsy and indecisive management that allowed the players to seize the moral high ground by default.

Commissioner William Eckert let each home team decide whether to play as scheduled. The Houston Astros intended to proceed with their April 9 opener, but backed off amid the threat of a boycott by the visiting Pittsburgh Pirates, a team with 11 African American players.

“We are doing this because we white and black players respect what Dr. King has done for mankind,” the Pirates’ players said in a statement.

By April 7, all but one opener had been postponed: the April 9 game between the Dodgers and Philadelphia Phillies, at Dodger Stadium. The Phillies’ players also pledged to boycott, with the support of their ownership. The Dodgers announced their intention to play.

“I don’t recall anybody on the Dodgers that said no,” outfielder Ron Fairly said recently.

Said pitcher Claude Osteen: “That was a time when most of us would go along with whatever was asked. That’s not to say we were not in shock [about the assassination]. We were. But I don’t recall any discussion about delay.”

The Dodgers’ opening day roster that year included one African American, outfielder Willie Davis. Buzzie Bavasi, the Dodgers’ general manager, told Davis the game would be played but he could be excused if he so desired.

“It is similar to the time when Sandy Koufax did not play because of religious holidays,” Bavasi told The Los Angeles Times.

Philadelphia first baseman Bill White, one of the Phillies’ six African American players, suggested that owner Walter O’Malley and his Dodgers — the team that had promoted Jackie Robinson to break baseball’s color barrier 21 years earlier — appeared primarily interested in protecting their sellout crowd for the opener.

“It angers me that the team that pioneered the advent of the Negro into baseball would take such a stand,” White told the Philadelphia Inquirer.

White later became the National League president, the first African American to occupy that position. Warren Giles, who held the office at the time, said the Phillies would have to forfeit if the Dodgers decided to play — a night game, on the day of King’s funeral.

“I see nothing disrespectful about the Dodgers playing so many hours after the funeral,” Giles said. “It is generally accepted practice for businesses to close during the services and reopen after they are over.”

Bavasi said the Dodgers would have postponed the game had it been scheduled for the afternoon, when it would have conflicted with King’s funeral.

“We are doing nothing disrespectful,” Bavasi told The Times. “Our main idea is to give the people some sort of amusement when they need it most.”

The Philadelphia Daily News blasted the Dodgers for prioritizing “greed and irreverence in an hour of grave national urgency and sorrow,” blasted Giles for presiding over a “gutless, owner-controlled regime,” and blasted Eckert for letting the situation deteriorate “close to anarchy by his failure to postpone all the openers by an executive decree.”

On the morning of April 9, O’Malley met with Bavasi, and shortly thereafter the team announced that the opener would be postponed. The Phillies would not show up, and they would not relent.

“There is no sense bumping our heads against a stone wall,” Bavasi told The Times.

Times columnist John Hall wrote: “These are particularly difficult and sensitive days, and Bavasi, innocently enough, may have been mistaken.”

Bavasi left the Dodgers two months later, to become the first president of the expansion San Diego Padres.

As a core of players pushed for the league to honor King beyond the postponements, O’Malley agreed to stage a charity game at Dodger Stadium.

“I feel that this is a fine way for the owners to show their support for a memorial tribute to my husband, his dream and for the cause of human dignity,” Coretta Scott King, his widow, wrote in a letter to O’Malley.

The league’s owners paid to send two top players from each team to the game, which was played on March 28, 1970. The event raised more than $30,000 for a fledgling King memorial center and for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the Atlanta-based civil rights organization King founded and had led.

“Sports can demonstrate that people can learn to work together and that nonviolence is not dead and buried with Dr. King,” said Andrew Young, then an SCLC director and later the U.S. ambassador to the United Nations, in Sport magazine.

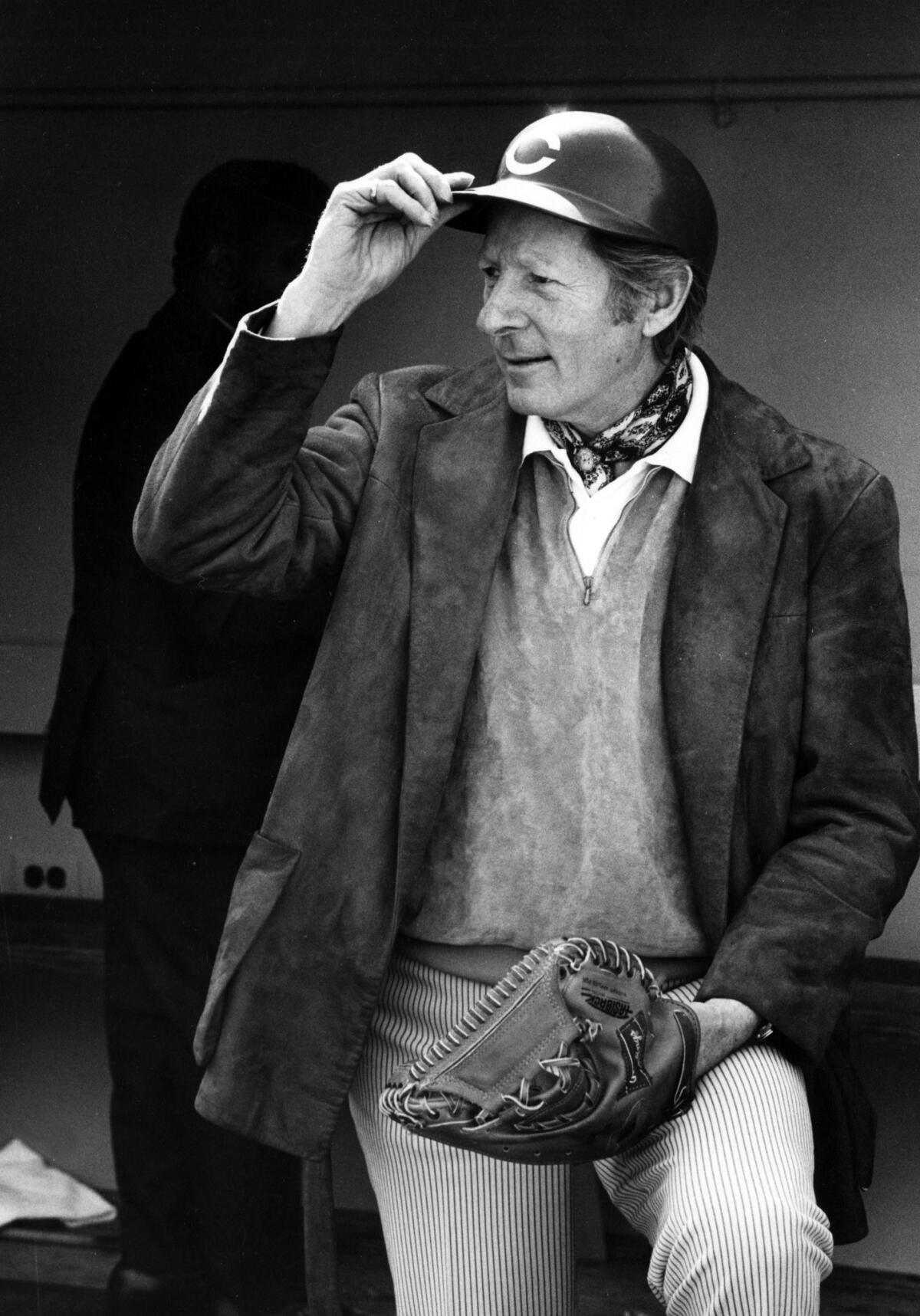

Hall of Famers Joe DiMaggio and Roy Campanella managed the teams in what was called the “East-West Major League Baseball Classic.” While the traditional All-Star format pitted the National League against the American League, this game featured the NL East and AL East players on one team, the NL West and AL West players on the other.

Campanella’s coaches included Sandy Koufax, Don Drysdale and Don Newcombe. DiMaggio’s coaches included Billy Martin, Stan Musial and Satchel Paige.

The star-studded rosters featured 15 future Hall of Famers, including Hank Aaron, Ernie Banks, Johnny Bench, Lou Brock, Roberto Clemente, Reggie Jackson and Tom Seaver.

Willie Mays flew in from Japan, where his San Francisco Giants were playing a spring training exhibition tour.

The retired Robinson, who told the Sporting News in 1968 that Mays was “a do-nothing Negro in the area of race relations” and who had kept his distance from the Dodgers and the league as minorities failed to advance into front offices and managerial jobs, made a rare Dodger Stadium appearance for the King benefit game.

Coretta Scott King threw out the ceremonial first pitch, after the Dodgers played recorded excerpts of her late husband’s “I Have A Dream” speech. Fairly, whom the Dodgers had traded to the Montreal Expos in 1969, was the most valuable player of what the Sporting News called “the first East-West major league baseball classic.”

“It was the first and only,” Fairly said.

A couple of months ago, a fan displayed an autographed baseball for Dodgers historian Mark Langill. There was a signature from DiMaggio, in the sweet spot between the laces, and signatures from Clemente and Seaver and an assortment of other legends.

The fan had absolutely no clue where the ball might have come from, and Langill excitedly realized the collectible had been a souvenir from the King benefit game.

“It was,” Langill said, “the greatest game nobody knows about.”

Follow Bill Shaikin on Twitter @BillShaikin

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.