How Saints fans rallied after losing to Rams in NFC title game

- Share via

NEW ORLEANS — Thomas Morstead refused to watch the most recent Super Bowl.

So he watched another one.

Morstead, a punter for the New Orleans Saints, participated this year in the region-wide boycott of the Super Bowl between the Rams and New England Patriots. Instead, he threw a party at his home and, for the first time, watched the full broadcast of the Super Bowl between the Saints and Indianapolis Colts from his rookie season nine years ago.

“I’d seen highlights, but I’d never sat down and watched the whole thing,” said Morstead, who successfully executed a surprise onside kick in that game. “It was cool to relive it. Cool to hear all my neighbors — they all remembered where they were when it happened.”

Around the city, untold thousands of scalded Saints fans did the same. It wasn’t just that their team had lost to the Rams in the NFC title game at the Mercedes-Benz Superdome, but it was how they lost, with officials missing a blatant pass interference by Rams cornerback Nickell Robey-Coleman.

The Saints and Rams meet again Sunday, this time at the Coliseum, eight months after what might be the most famous no-call in NFL history.

A play-by-play look at the final drive that pushed the Rams into the Super Bowl last season in last year’s controversial NFC title game against the Saints.

The situation in question: With 1 minute 45 seconds on the clock, the score tied, 20-20, and the Saints 13 yards from the Rams’ end zone, Drew Brees dropped back to pass on third-and-10. Receiver Tommylee Lewis ran a wheel route on the right side, and Brees fired a pass in his direction. Before the ball got there, however, Robey-Coleman clocked Lewis with a hit initiated by the helmet that sent him sailing out of bounds.

The ball fell to the Superdome turf, but a flag never did. The situation was so controversial and consequential that the NFL would later change its rules to address it.

“All [Robey-Coleman] was doing was staring down Lewis and just playing the man. He never got turned on him,” Fox color man Troy Aikman said during the slow-motion replay. “It can’t get any more obvious than that.”

Saints Coach Sean Payton raged on the sideline, and the crowd booed wildly, even as the home team kicked a field goal to take the lead.

The Rams went on to tie with a Greg Zuerlein field goal and secure a trip to the Super Bowl in overtime with another field goal.

As the Rams celebrated in the locker room, even Robey-Coleman had to concede he got away with one.

“Yes, I got there too early,” he said. “I was beat, and I was trying to save the touchdown.”

In huge type the next day, stripped across the top of the front page of the New Orleans Times-Picayune, was the headline “REFFING UNBELIEVABLE.”

The city roiled with anger and brushed aside the counterargument that the Saints benefited from other missed calls in the game, including an apparent facemask of Rams quarterback Jared Goff by linebacker A.J. Klein on the previous drive. That would have given a first down to the Rams on the New Orleans 1 — likely leading to a touchdown rather than a field goal.

What’s more, the Saints got the ball first in overtime, but the Rams intercepted a Brees pass to set up the win. In other words, the no-call didn’t mark the end of the game.

Still, there was a belief among many Saints fans that a conspiracy was afoot, that the NFL didn’t want their team in the Super Bowl, and perhaps that this was a continuation of the blowback from the so-called Bountygate scandal. That was when the Saints were accused of paying bonuses to players for injuring opponents, a practice that allegedly took place from 2009 to 2011 and led to a slew of suspensions and fines.

There was consternation about the composition of the officiating crew, headed by referee Bill Vinovich of Newport Beach, which included three other members from Southern California. The NFL declined to make Vinovich available for this story, in keeping with their rule banning officials from speaking to the media during the season, except to pool reporters at games after calls requiring further explanation.

Sign up for our free sports newsletter >>

What’s more, the NFL’s practice of assembling all-star officiating crews for the playoffs, rather than keeping the regular-season crews intact, came under fire from Payton and others.

“We can’t have an all-star crew and sit there and stare at a play like that,” Payton said. “That honestly is called correctly not only in high school Friday night, that call is made correctly in youth football. This is supposedly our best and our best wasn’t good enough.”

There were multiple fan lawsuits that claimed fraud and conspiracy over the decision not to throw that flag. One got as far as the Louisiana Supreme Court, which dismissed the case in early September, its ruling citing a previous precedent that stated: “It is not the role of judges and juries to be second-guessing the decision taken by a professional sports league purportedly enforcing its own rules.” The other lawsuits have been tossed out.

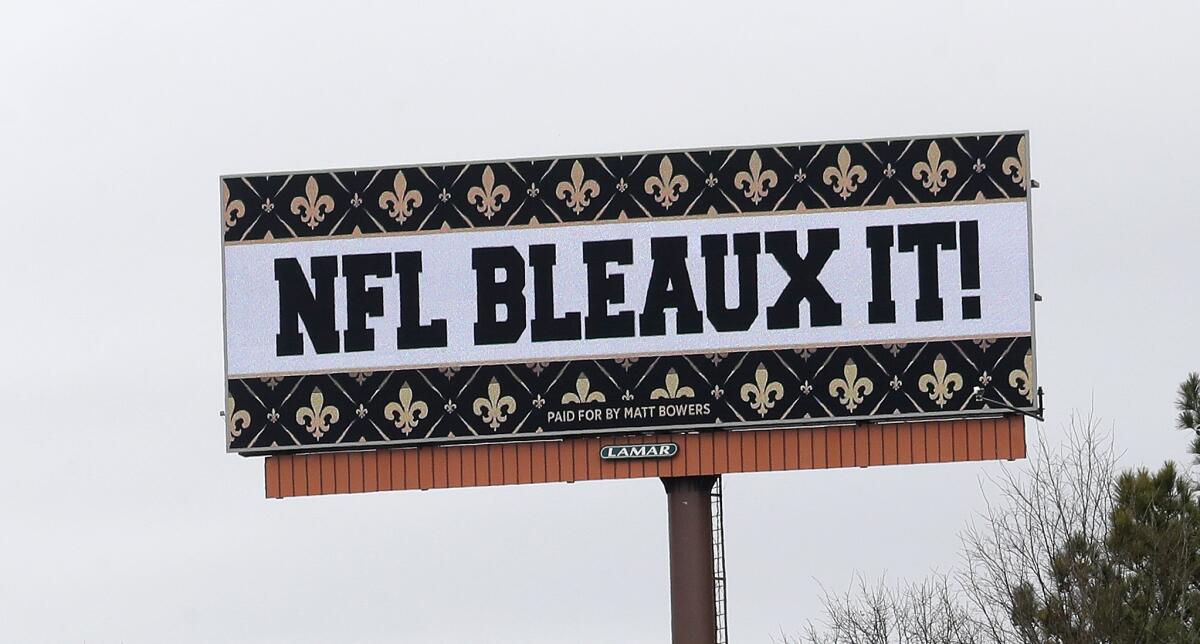

After the no-call and loss, the idea of a Super Bowl boycott took hold. Bars showed replays of Saints over Colts, and some used the “Madden” video game to simulate a Saints-Patriots Super Bowl. The actual game delivered just a 26.1 overnight rating for CBS, the city’s lowest-ever Super Bowl rating.

The next day, the Times-Picayune printed a blank front page but for the headline, “Super Bowl? What Super Bowl?” So popular was that edition, the newspaper had to print it a second time.

::

For many in New Orleans, there was a fatalistic sense of: “Of course this would happen to us.”

“We are a people that have a sense of doom, for good reason,” said political commentator and New Orleans fixture James Carville, who taught at Tulane University. “We’re probably living in a doomed place. Every other place in the United States kind of knows it’s going to be here 50 years from now. No thinking New Orleanian believes that our existence is guaranteed 50 years from now. So we live under a cloud of doom.”

Not surprisingly, a month after the no-call, the gaffe was the overriding theme of the annual Mardi Gras parade.

“There was definitely a lot of ‘Saints got robbed’ coming from the crowd,” recalled tackle Terron Armstead, who rode on a float with several teammates and coaches. “The no-call. All that. But it was Mardi Gras, a celebration. Everybody’s out enjoying themselves and expressing themselves at the same time. We had a ton of feelings going through our mind, still. That was a great way to get out and interact, jump in the crowd with fans.”

Drew Brees and the Saints visit L.A. to play the Rams in a rematch of the NFC championship game that already could have playoff ramifications.

There was, and still is, a sense of dark humor that accompanied the anger, a typical reaction among fans who for years wore paper bags over their heads to anonymously cheer their perennially losing “Aints.”

A neighbor of legendary Saints quarterback Archie Manning has a yard sign that reads, “Hey, mister, throw me something.” It’s a phrase familiar to anyone who has ever flung a string of beads into a crowd off a Mardi Gras float. Only the sign is adorned with yellow officiating flags.

“It’s a magical city, no other place like it,” Armstead said. “They celebrate pain. They try to find the positivity in any situation, or just try to uplift spirits. That single-handedly is what makes this city special.”

NFL franchises have individual owners, but in a lot of cities, the team is more of a public trust that everyone owns. That’s especially true in New Orleans, where in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, some fans used their FEMA money on Saints season tickets.

These Saints truly belong to the community.

“I can walk into Walmart and get coached up by somebody in the potato-chip aisle,” Armstead said. “They coach you on everything. ‘You need to get your first step a little bit faster.… Tell Drew he needs to.…’ OK, I’ll tell a Hall of Famer how to do his job.

“They’re passionate.”

Exacerbating the pain of losing the conference championship game was that the Saints saw their Super Bowl dream die in shocking fashion the year before too. They lost a divisional playoff at Minnesota on the final play of the game, when Vikings quarterback Case Keenum threw a 27-yard pass to Stefon Diggs, who slipped past safety Marcus Williams and ran to the end zone for a 61-yard touchdown for a 29-24 victory. The play is now known as the Minneapolis Miracle.

Fox’s Joe Buck, who was the play-by-play announcer for both games, compared the reaction of Saints fans to that of Chicago Cubs faithful with the Steve Bartman incident in the 2003 National League Championship Series.

In that instance, Bartman, a Cubs fan, reached for and deflected a foul ball at Wrigley Field, disrupting a potential catch by Cubs outfielder Moises Alou. It turned out to be a pivotal play in the demise of the Cubs, who failed in their attempt to win their first National League pennant since 1945.

“Baseball fans know that after the Bartman thing happened, the Cubs failed to turn a double play, it was only Game 6, you have an opportunity to win Game 7, you have your best pitcher going, and then they didn’t win,” Buck said.

“Fans are always looking for someone to blame, whether it’s the announcer, the referee or whatever. It’s always, `’Well, why don’t they want us to win?’ It’s just ridiculous. The league and officials don’t work that way.”

Los Angeles Rams cornerback Nickell Robey-Coleman knows he has become a household name since his helmet-to-helmet hit on TommyLee Lewis in the NFC title game.

But it was enough of a problem to NFL owners that they voted this offseason to change the rules, making pass-interference calls — and no-calls — subject to instant-replay review. It’s not a perfect solution.

“None of us will ever agree what defensive pass interference is,” said Tampa Bay Coach Bruce Arians, a member of the league’s competition committee. “There’s 10 defensive coaches, and we’re showing this clip and saying, `’That’s defensive pass interference.’ They’re saying, `’No, it’s not.’ That stuff gets pretty heated. That’s probably the hardest part. How are we going to define what is and what isn’t? The only way you can is the letter of the law. With instant replay, you have to slow it down and see.”

So how could an official miss such blatant pass interference? Former NFL referee Mike Carey points to the league’s adherence to the so-called bang-bang play, which basically says if the ball and the defender arrive at the receiver at roughly the same time, and the ball is knocked loose, the pass is incomplete.

Carey said the best officials have a keen enough eye to make nuanced calls, but that the bang-bang concept allows for a universal standard that levels the playing field for less-skilled officials.

“The league doesn’t want a foul called when there wasn’t one,” Carey said. “But that axiom is tough. What’s bang-bang if the ball’s coming that fast? Over time, bang-bang has become bang … bang.”

That said, Carey conceded: “This one should have been called.”

For Saints players, this is a new season and a new roster. They know it’s fruitless to live in the past. But for their fans, the no-call is a rallying cry.

“The NFL can bend the rules as much as they want, but I almost feel we have some kind of higher power on our side now,” said Saints fan Michael Fredrick, a web designer in New Orleans. “You can try to push us down. But the problem is, we’re a great team and you’re not going to stop us.”

As for the Rams, they have long since moved on. In addressing the no-call this week, cornerback Aqib Talib echoed the sentiments of many Rams teammates and fans.

“That’s a New Orleans problem,” he said. “It’s not an L.A. problem.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.