Online school put U.S. kids behind. Some adults have regrets.

- Share via

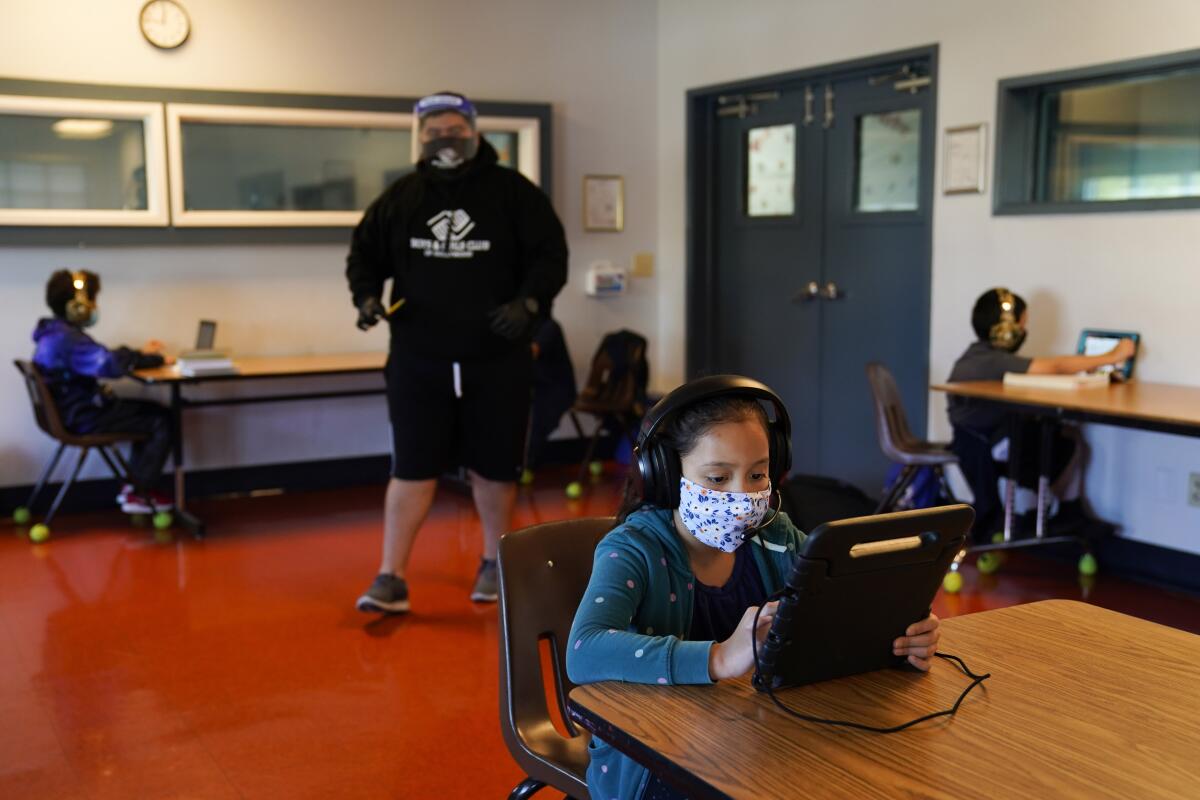

BOSTON — As the harmful effects of extended pandemic school closures become more apparent, some educators and parents are having regrets.

They’re questioning decisions in cities across the U.S. to keep classes online long after clear evidence emerged that schools weren’t COVID-19 super-spreaders — and months after life-saving adult vaccines became widely available.

In Chicago, Marla Williams initially supported the decision to instruct students online during the fall of 2020. Williams, a working single mother, has asthma, as do her two children. She enlisted her father, a retired teacher, to supervise her children’s studies. It didn’t work.

Her son lost motivation and wouldn’t do his assignments. Once he went back on a hybrid schedule in spring 2021, he started doing well.

“I wish we’d been in person earlier,” Williams said. “Other schools seemed to be doing it successfully.”

There are fears for the futures of students who don’t catch up. They risk never learning to read, long a precursor for dropping out of school. They might never master algebra, putting science and tech fields out of reach. The pandemic decline in college attendance could accelerate, crippling the U.S. economy.

In a sign of how inflammatory the debate has become, there’s sharp disagreement about how to label the problems created by online school. “Learning loss” has become a lightning rod; some fear it might brand struggling students or cast blame on teachers.

Regardless of what it’s called, the casualties of Zoom school are real.

The scale of the problem and the challenges in addressing it were apparent in interviews with nearly 50 school leaders, teachers, parents and health officials, who struggled to agree on a way forward.

A Los Angeles Times analysis of data offers an alarming assessment of the impact of the pandemic on L.A. students.

Some warned against second-guessing school closures for a virus that killed more than 1 million people in the U.S. More than 200,000 children lost at least one parent.

“It is very easy with hindsight to say, ‘Oh, learning loss, we should have opened.’ People forget how many people died,” said Austin Beutner, former superintendent in Los Angeles, where students were online from March 2020 until the start of hybrid instruction in April 2021.

The question isn’t merely academic. It’s conceivable another pandemic might emerge — or a different crisis.

But there’s another reason for asking what lessons were learned: the kids who have fallen behind. Some third-graders struggle to sound out words. Some ninth-graders have given up on school because they feel that they are so behind they can’t catch up. The future of American children hangs in the balance.

In the pandemic’s latest hit on education, the number of L.A. Unified students who have been chronically absent this school year has doubled.

When COVID-19 reached the U.S., scientists didn’t fully understand how it spread or whether it was harmful to children. American schools, like most around the world, shuttered in March 2020.

That summer, scientists learned that kids didn’t face the same risks as adults, but experts couldn’t decide how to operate schools safely.

The risk assessment varied depending on how vulnerable a community felt to the virus. Another factor was politics: Districts that reopened tended to be in areas that voted for President Trump or had largely white populations.

By winter, schools that used masks and distancing weren’t contributing to increased COVID-19 spread in the community, studies showed. Once the vaccine was available, some Democratic-leaning districts started to reopen.

Yet many schools stayed closed well into the spring, including in California, where the powerful teachers unions fought returning to classrooms, citing lack of safety protocols.

Nationally, kids whose schools met mostly online in the 2020-21 year performed 13 percentage points lower in math and 8 percentage points lower in reading compared with those in schools meeting mostly in person, according to a 2022 study by Brown University economist Emily Oster.

The setbacks have some grappling with regret.

National assessments show that 9-year-olds suffered big drops in reading and math scores, with students who were already struggling seeing the biggest decline.

“I can’t imagine a situation where we would close schools again, unless there’s a virus attacking kids,” said Eric Conti, superintendent for Burlington, Mass.

Still, many school officials said that even with hindsight, they’d have kept schools online well into 2021. Only two superintendents said they’d likely make a different decision.

In some communities, the historic underinvestment in schools loomed large. In the South, Black Americans’ fear of the virus was sometimes coupled with mistrust of schools rooted in segregation. Schools were shuttered in Atlanta, Nashville, Jackson, Miss., and other Southern cities — in some cases, for nearly all of the 2020-21 year.

In Clayton County, Ga., home to the state’s highest percentage of Black residents, schools chief Morcease Beasley said the fear in his community was overwhelming.

“I knew teachers couldn’t teach if they were that scared, and students couldn’t learn,” he said.

Pandemic-forced school closures revealed how grade-point systems hurt disadvantaged children, prompting educators to look for ways to bring equity to grading.

Among teachers, there’s some dispute about online learning’s impact on children. But many fear some students will be scarred for years.

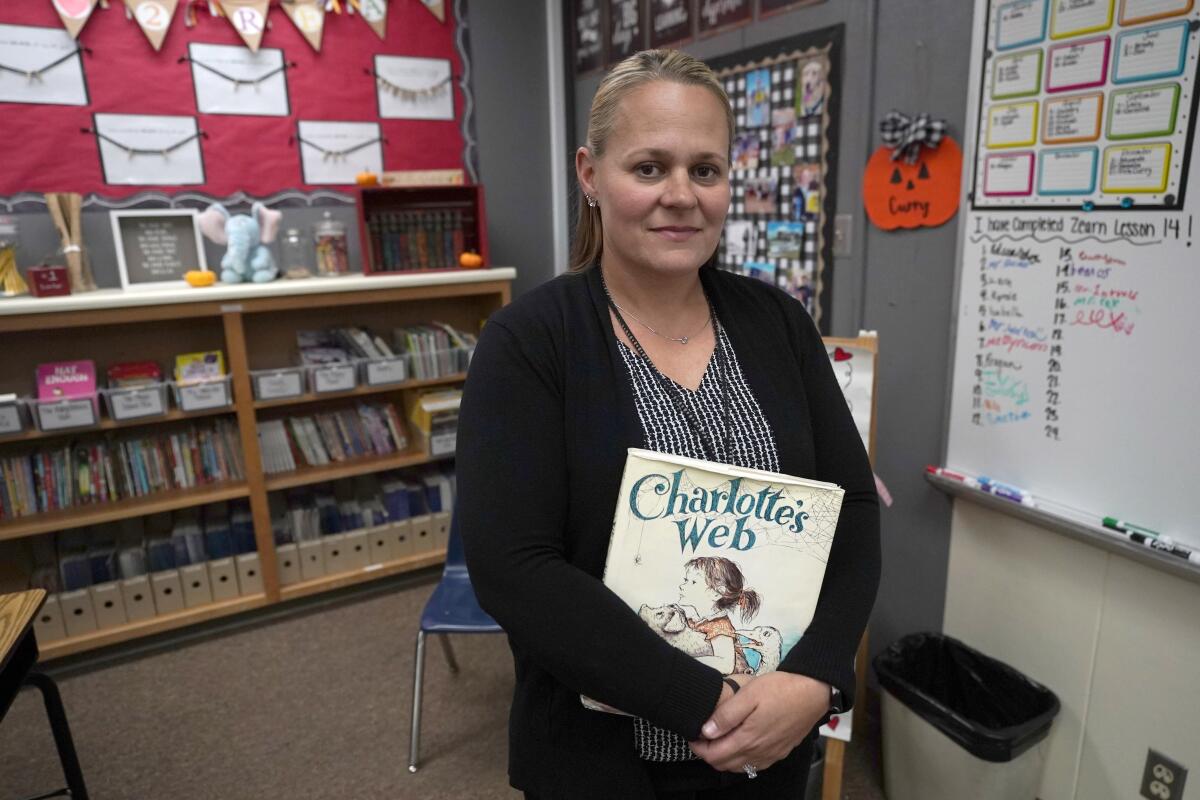

“Should we have reopened earlier? Absolutely,” said teacher Sarah Curry in California’s rural Central Valley.

But the nation’s 3 million public school teachers are far from a monolith.

Jessica Cross, who taught ninth grade math on Chicago’s west side at Phoenix Military Academy, feels that her school reopened too soon.

“I didn’t feel entirely safe,” she said.

A representative from the American Federation of Teachers declined in an interview to address whether the union regrets the positions teachers took against reopening schools.

“If we start to play the blame game,” said Fedrick Ingram, AFT’s secretary-treasurer, “we get into the political fray of trying to determine if teachers did a good job or not. And I don’t think that’s fair.”

Regrets or no, experts agree: America’s kids need more from adults if they’re going to be made whole.

The country needs “ideally, a reinvention of public education as we know it,” Los Angeles Supt. Alberto Carvalho said. Students need more days in school and smaller classes.

Experts say intensive tutoring, Saturday school or doubling up on math or reading during a regular day would also help.

Too few districts have made those investments, Harvard economist Tom Kane said. Summer school is insufficient, Kane said — it’s voluntary, and many parents don’t sign up.

Gecker reported from San Francisco. Collin Binkley in Washington, D.C., Sharon Lurye in New Orleans, Arleigh Rodgers in Indianapolis, Claire Savage in Chicago and Brooke Schultz in Harrisburg, Pa., contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.