A Times critic looks forward to a bright future backlit by a decade of brilliant theater

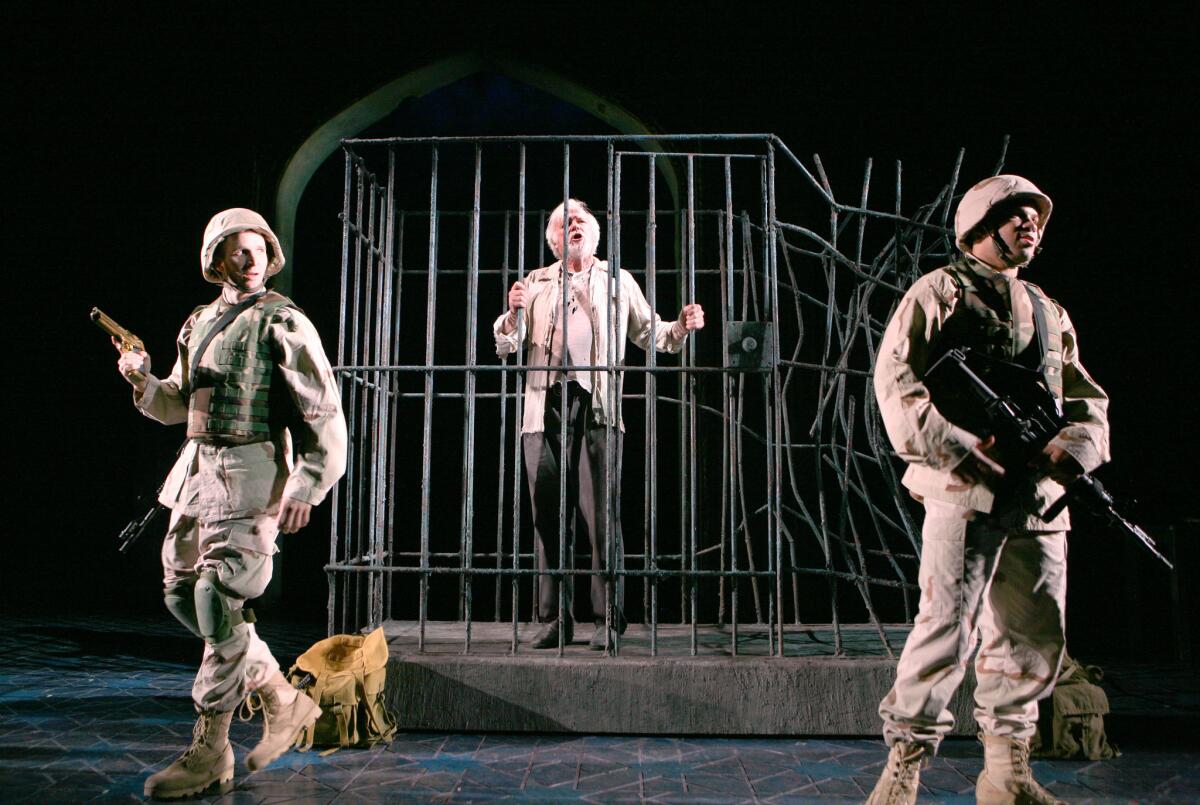

Brad Fleischer, left, Kevin Tighe and Glenn Davis in Rajiv Joseph’s “Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo” at Kirk Douglas Theatre in Culver City in May 2009. It was “electric.”

- Share via

Sometimes the word “unforgettable” can be taken literally.

I can still feel that electric charge when I first encountered Rajiv Joseph’s “Bengal Tiger at the Baghdad Zoo” in 2009. The world premiere at the Kirk Douglas Theatre of this Iraq War drama represented not just the bold emergence of a globally attuned theatrical imagination but a notable victory of dramatic poetry over earnest reportage.

Yet after 10 years of writing about the theater for The Times, I’m occasionally surprised to discover that a play that has piqued my interest from reports elsewhere in the world is one that I actually reviewed years earlier in L.A. That, my journalist friends tell me, is a function of passing the 1,000-byline mark.

See more of Entertainment’s top stories on Facebook >>

But I don’t have to tunnel through my archives to recall the most vigorous dramas of the last decade. Some work stands apart from memory’s clutter.

Annie Baker’s “Circle Mirror Transformation,” which was done at Costa Mesa’s South Coast Repertory in 2011, more than lived up to the expectations that were raised by her army of New York devotees. More impressive still, her Pulitzer Prize-winning play “The Flick,” which divided audiences when it premiered at New York’s Playwrights Horizons in 2013, established her as one of the brightest stars in this new galaxy of playwriting prodigies.

I was introduced to Tarell Alvin McCraney’s “The Brother/Sister Plays” at New York’s Public Theater, which produced all three plays in repertory in 2009. But it was through seeing parts of the trilogy at the Fountain Theatre (which produced “In the Red and Brown Water” and “The Brothers Size,” both under Shirley Jo Finney’s lyrical direction) and San Diego’s Old Globe (which presented “The Brothers Size,” expertly directed by Tea Alagic), that I became better acquainted with this path-breaking talent. (McCraney, whose vastly different “Choir Boy” was memorably staged at the Geffen Playhouse in 2014, has the courage not to stylistically repeat himself.)

The Old Globe’s 2014 production of Quiara Alegría Hudes’ Pulitzer Prize-winning “Water by the Spoonful,” directed by Edward Torres, conveyed the full communal weight of the play’s love and pathos. So deeply affected was I by this drama that I spent much of the long and lonely drive home from San Diego reflecting on what an extraordinary generation of American dramatists this is.

Veterans held their own. “Vanya and Sonia and Masha and Spike” earned the ever-outrageous farceur Christopher Durang the Tony Award, a capstone to a career in hilarity. David Hyde Pierce’s 2014 production at the Mark Taper Forum, starring Christine Ebersole in divine diva mode, showed that Los Angeles could improve on the Broadway original.

As for uncategorizable charm, I don’t know if anything could equal Britain’s National Theatre production of Alan Bennett’s “The History Boys,” which I saw on Broadway in 2006, with Richard Griffiths lending all his eloquence and emotional heft to the role of the inspiring teacher with inappropriate hands. (Too bad the Ahmanson Theatre production offered such a weak approximation.)

“The History Boys” with Dominic Cooper, left, Clive Merrison, Richard Griffiths and Stephen Campbell Moore.

But even more than the plays or the productions, it’s the voices of performers that haunt me. Roger Guenveur Smith, acting in a style that approximated pure jazz, cast an enthralling spell in “Rodney King,” his 2013 performance piece at the Douglas that broadened our understanding of the man at the center of the L.A. riots.

I can still hear Anna Deavere Smith as the director of a South African orphanage filled with children with AIDS expressing gratitude to a dying girl for the privilege of taking care of her in “Let Me Down Easy.” The memory of this scene spontaneously seizes hold of me from time to time, a testament to the power of uncalculating goodness and as moving to me today as it was when I first saw the production at San Diego’s Lyceum Stage in 2011 and then again later that same year at the Broad Stage in Santa Monica.

“Indelible” is the only way to describe Viola Davis’ Tony-winning turn as Rose in the 2010 Broadway revival of August Wilson’s “Fences.” Her grief after learning that her husband, Troy (played by Denzel Washington), fathered a child with another woman (“I done tried to be everything a wife should be”) set in motion a tidal wave of cathartic emotion that I’ve yet to see equaled.

Viola Davis and Denzel Washington in “Fences.”

If I could rewind the clock on musicals, I would jump at the chance of catching Patti LuPone perform “Rose’s Turn” as the most virtuosic nervous breakdown in psychiatric history in the 2008 Broadway revival of “Gypsy.” Then I’d dart to see Douglas Hodge wring every ounce of dignified self-assertion from the number “I Am What I Am” in the 2010 Broadway revival of “La Cage aux Folles.” After this, I’d run to watch Hannah Waddingham treat each word of “Send in the Clowns” as though it were coined expressly for London’s Menier Chocolate Factory’s 2008 ingenious revival of “A Little Night Music” (a production that lost a good deal of its magic when it was glitzed up for Broadway with Catherine Zeta-Jones in 2009).

If my columns early on were filled with objections over the spate of ditsy jukebox musicals, I made up for it with praise of the bracing productions of Stephen Sondheim classics by John Doyle and others. I admit that for a few years I had almost lost hope for the American musical, but two recent shows, “Fun Home” and “Hamilton,” both of which started at the Public Theater, have turned me into a cockeyed optimist every bit as much as Nellie Forbush from “South Pacific” (to invoke one of director Bartlett Sher’s many triumphant revivals).

My experience of Shakespeare in the last several years has reluctantly turned this abstainer of “Downton Abbey” into an Anglophile. Nothing I’ve seen stateside can compare with Nicholas Hytner’s National Theatre production of “Much Ado About Nothing,” with Zoë Wanamaker and Simon Russell Beale as a decidedly middle-aged Beatrice and Benedick. Hytner’s National Theatre staging of “Othello,” with Adrian Lester as an unusually suave Moor and Rory Kinnear as a crafty military careerist Iago, moved with laser-like intensity. But the award for best Othello goes to Chiwetel Ejiofor, who interpreted the role as a heartbroken racial outsider in Michael Grandage’s 2007 production at the Donmar Warehouse. Mark Rylance’s nonpareil turn as Olivia in the Shakespeare’s Globe all-male production of “Twelfth Night” on Broadway proved to this doubter that Shakespeare’s festive comedy really can make people laugh.

International theater of a more groundbreaking bent has been in short supply here since the Great Recession. Kristy Edmunds of the Center for the Art of Performance at UCLA is a dynamic leader, but I hope she hasn’t conceded the budgetary battle over importing this kind of work. CAP’s presentation of “Shun-kin,” a collaboration between the London-based company Complicite and Japan’s Setagaya Public Theatre, was a visually stunning high point of the 2013 Radar L.A. festival (a citywide event I’d like to see become at the very least a biennial offering).

I wish both the naturally eclectic REDCAT and the more expansive-minded CAP would receive windfalls that would permit them to more regularly produce experimental theater. But in the meantime, perhaps the large nonprofits might consider one less superfluous Mamet retread for something by Ivo van Hove. (His 2014 production of “Scenes From a Marriage” at New York Theatre Workshop was a miraculous reinvention.) L.A. has seen some first-rate revivals (the Taper’s “Waiting for Godot” and “Bent”; yes, even the Geffen’s blue-collar handling of Mamet’s “American Buffalo”). Why not extend an invitation to the much sought-after Belgian director, who’s deconstructing Arthur Miller on Broadway?

No surprise that many of the best L.A. productions were produced by 99-seat theaters. Yet part of what made these offerings so memorable was that each one, unaccompanied by hype, felt like a serendipitous discovery.

I had seen “Blackbird,” David Harrower’s disquieting two-hander about a young woman who confronts the man who sexually abused her as a girl, at Manhattan Theatre Club in a production starring Jeff Daniels and Alison Pill. (A Broadway production with Daniels and Michelle Williams opens this season.) But nothing prepared me for the scalding intensity of Robin Larsen’s 2011 staging of the play at Rogue Machine Theatre. The production (starring the perfectly matched Corryn Cummins and Sam Anderson) cannily exploited the pressure-cooker-like dimensions of this pocket venue.

When I first heard about Aaron Posner’s play “Stupid ... Bird,” I rolled my eyes not so much at the unprintable title but at the prospect of yet another winking update of Chekhov. But how relieved I am not to have missed this insouciantly boundary-blurring play when it was done at Pasadena’s Theatre @ Boston Court (in a co-production with Circle X Theatre Co.) in 2014. The production, sensationally directed by Michael Michetti, featured a top-notch ensemble that was able to balance the Russian master’s psychological richness with his contemporary disciple’s madcap postmodernism.

I confess to a curious fondness for Black Dahlia Theatre’s 2008 world premiere of Jonathan Tolins’ “Secrets of the Trade,” about the relationship between a boy who dreams of Broadway and the flamboyant mentor who agrees to show him the ropes. Matt Shakman’s production (starring a delectably hammy John Glover) was so crisply acted that the play’s meandering nature was covered up by its histrionic charm.

Carping comes easily when a play leaves you cold. But this last decade has shown me that it’s not perfection I’m seeking as a critic. I want to be moved, challenged and dazzled. If my mind can’t be blown, then at least force it to undergo a sea change.

Something else I want to experience is community — the community of dedicated theater artists and engaged audiences who recognize the stage as a gathering space for ideas and emotions that haven’t adequate outlets elsewhere in society. I think this may be part of the reason there’s such fervor to protect some semblance of the old 99-seat Theater Plan that Actors’ Equity Assn. has been keen to overhaul.

I could mention other intimate theater highlights during my tenure (Antaeus Theatre Company’s “Top Girls” and “Peace in Our Time,” Rogue Machine’s “A Permanent Image” and “Dying City,” the Theatre @ Boston Court’s “R II,” the Fountain’s recent “The Painted Rocks at Revolver Creek,” Pacific Resident Theatre’s “The Browning Version,” Echo Theatre Company’s “Firemen,” the Odyssey Theatre’s “Fences” starring the brilliant Charlie Robinson), but I wouldn’t want to argue on behalf of the status quo. I wish a path to growth could be agreed upon by all parties. Institutions as vibrant as the ones I’ve just mentioned shouldn’t be encouraged to remain shoestring operations.

If money is the stumbling block, patronage is the solution. I have been hard on the leaders of the big nonprofit theaters for not putting up more resistance to the tide of commercialization. I understand the problem somewhat differently today than I did five years ago. I think artistic directors need to see themselves less as impresarios and more as community leaders. To realize their artistic visions, they must communicate directly to their audiences what they are trying to accomplish and why the support of loyal patrons is indispensable.

Treating theatergoers like consumers will lead to only more seasons top-heavy with marketing-driven programming. Good entertainment is nothing to sneeze at, but the stage is an art form that takes us out of our virtual niches and joins us for a few hours into a flesh-and-blood collective. Now that’s a sales pitch I’d like to see employed in the next 10 years.

ALSO:

The best theater of 2015 highlights transformation and enduring power from L.A. to Broadway

Self-criticism: A theater critic’s search for nuance in the age of Yelp

‘Color Purple’ musical on Broadway has a divine, moving spirit

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.