Q&A: Braddock’s LaToya Ruby Frazier takes on Levi’s and ‘ruin porn’ chic

- Share via

An abandoned Beaux Arts train station in Detroit. A wheezing old theater in Youngstown, Ohio. A crumbling 19th-century school on the outskirts of Pittsburgh. In recent years photographers, both amateur and professional, have taken to chronicling the vestiges of manufacturing in the Rust Belt. So-called “ruin porn” has been featured in galleries and in books and it has been the subject of much scrutiny and analysis.

Yet these romanticized landscapes are not as empty and abandoned as they might seem.

Photographer LaToya Ruby Frazier was raised in the steel mill town of Braddock, a few miles east along the Monongahela River from Pittsburgh. Her family has lived in the area for generations. They have worked in the mill (which is still operational). And they have lived its decline, as well as the decline of the community around it. They even carry its contaminants in their blood. (Frazier has lupus and her mother is currently battling cancer.)

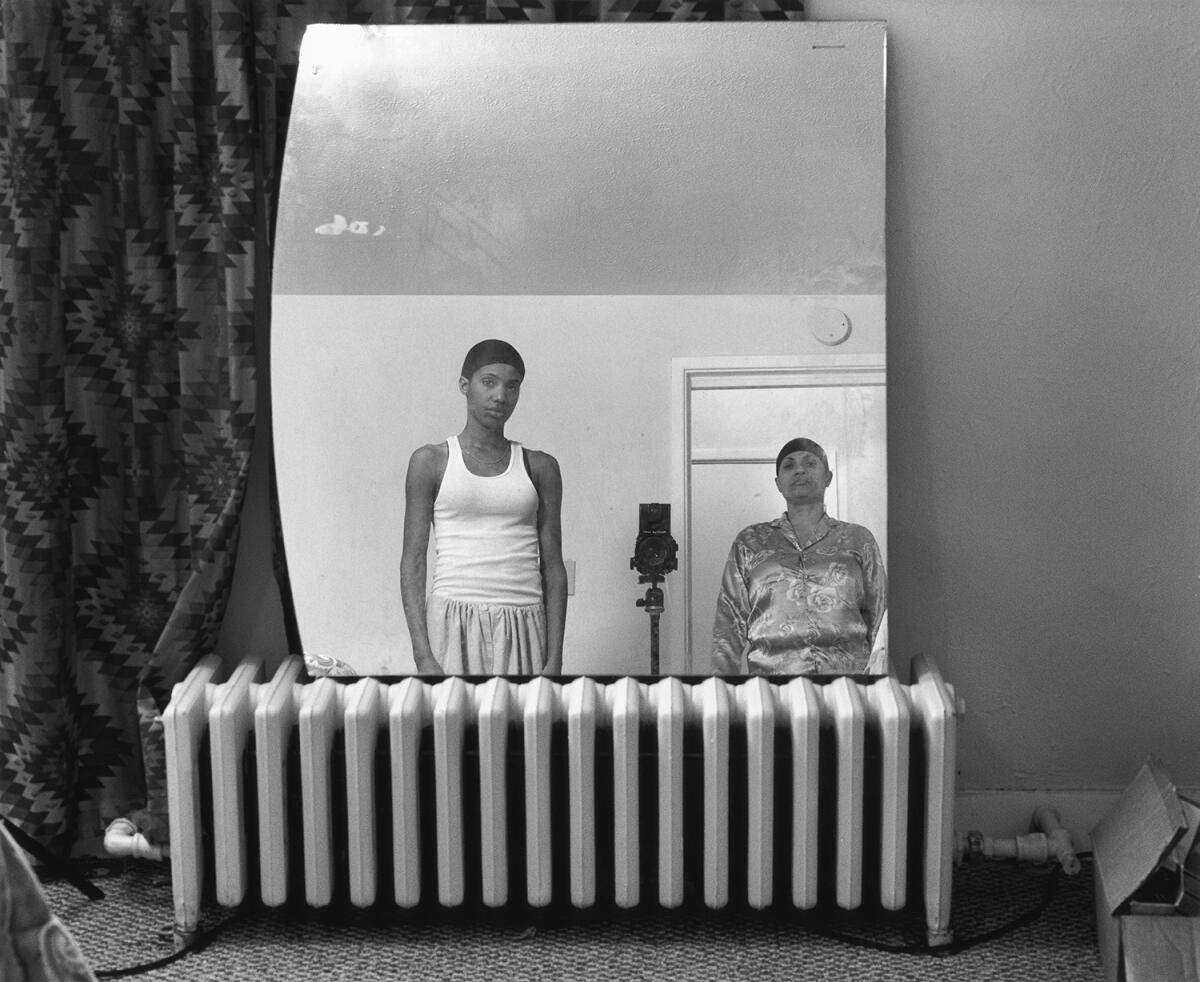

Through her photography — stark black-and-white, gelatin silver prints — the artist has made a record of the people who inhabit these post-industrial landscapes: herself, her mother, her grandmother, her mother’s boyfriend, her extended social network, people who have survived decades of grueling work, as well as globalization, de-industrialization and a drug war. You can see the wear and tear of these events written on their faces.

Frazier’s images have been shown at the Brooklyn Museum in New York and the 54th Venice Biennale in Italy, among countless other venues. And this fall, they were gathered into a striking new book, “The Notion of Family,” published by the prestigious Aperture Foundation.

Now an assistant professor of photography at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, she took time for a lengthy conversation via Skype (which I’ve condensed) about the importance of recording her family’s history, the ways in which her town has been portrayed in the media, and her interest in the workers who inhabit other steel centers.

I read on the New York Times Lens blog that part of the impetus behind your work was seeing a book about Braddock that didn’t include a trace of its African American residents. Could you tell me about that?

The book was by a publisher that produces books on small towns across America. I had already been shooting my family and the town for six years at that point. I had begun photographing outside, looking at landscape, architecture, collaborating with community members. I wanted to get the full history of [Braddock] and its melting pot. So I go get this book and take it back to my studio and it’s this slow, crawling feeling as I turn to the last page and I realize there’s not one African American from Braddock in this book.

That’s when it hit me. I may have thought that I was an innocent teenager making work about my mother and grandmother. But it was really a foreshadow that I’d be writing Braddock’s history. It made me realize that my work was bigger than me.

There are a lot of photographers who have chronicled the decline of industrial towns — the whole phenomenon of ruin porn — but their photographs are often free of people. What do you make of that?

I grew up with those images in the press, in mass media. My work is counter-narrative and a push back against this type of romanticizing. It’s not romantic. There’s nothing beautiful about it. I’m showing the human cost of the global economy and the failure of our government to regulate the steel industry, the environmental ruin it has caused. That’s the major focus of my work: the body and the landscape.

What led you to pick up a camera in the first place?

My senior year of high school I took a disposable camera and took pictures of everyone who used to ride my bus. I thought, “We survived a really rough period of the war on drugs.” And I was moved to shoot the pictures of the people who had graduated from that. It really started there.

But I didn’t really become aware of the possibilities until I started my intro to photography class at Edinboro (University, where I did my undergraduate work). I was shooting portraits and my teacher described them as “very August Sander.” He said, “You really have to change your major to photography.” I’d been studying graphic design. It began to seem crazy to think about color swatches for some company while I had major issues at my doorstep.

Was that the moment that drove you to take on your family’s story and Braddock’s story as a full-fledged project?

Well, it all came full circle meeting Kathe Kowalski, a professor at Edinboro. She was tough, she was a feminist, she committed her whole practice to photographing families living in rural poverty. She photographed women in prison and did workshops with them. She photographed her mother. She was clearly placed in my life for a reason.

I had started shooting 35 mm with my mom, but I was ashamed to show it. I wasn’t sure the feedback my peers would give me. I didn’t think that was “work.” Kathe knew that I wasn’t putting up my work in crit [critique sessions]. So she pulls me aside one day in her office and she asked to see the negatives that I’d been hiding. She said that the work was valid and that I needed to keep shooting. And she handed me three books: Eugene Richard’s “Cocaine True, Cocaine Blue,” Larry Clark’s “Tulsa” and a catalog for a show by Carrie Mae Weems.

These are very specific books subject matter-wise and politically. So I knew that she was kind of challenging me with an assignment: to connect these three bodies of work. When someone hands you three books like that, you know it’s going to be a long journey. I dedicated my book partly to Kathe.

A lot of your images are quite collaborative, especially the ones with your mother. How did that come about? Why cede control?

These things happened in an innocent way. I had a 35 mm camera and I engaged my mother. And she would have ideas. She would call me up because she’d had a surgery and she wanted to show some incision or the cancer that was cut out of her breast. She wanted me to document how her body was failing along with the social fabric of the town.

Well, it quickly moved from me shooting a 35mm and following her down the street to me coming home with a medium format and lights and it became about directing body language and the image. She is quite a character. The image that’s on the cover of the book: That’s her shooting that photograph. She’s the one holding the cable release.

How much staging do you do in your photographs? How constructed are the scenes that we see in your images?

I wouldn’t say staged. They’re more like living tableaux. It’s about letting the camera sit and letting it record whatever actions happen in front of it. I’m familiar with the space. I know every idiosyncratic detail. I know how to frame those rooms. But the actions were not staged or controlled. I call it conceptual documentary art. It slides between that realm of documenting our health, documenting our illness and also just kind of documenting our relationship in front of that camera.

Which brings me to one of the most remarkable images in the series, one in which you’re sitting next to your grandmother, wearing pigtails. Your face is so bright and youthful and hers is world-weary. How did that image come about?

It happened very quickly. I’d made a comment how she used to do my hair in pigtails, so she did them. The camera was on a tripod about 3 feet away from us. My grandmother was cleaning her dolls and I go in and sit there. No one else is there. We both turn and look and that’s when I hit the cable release. I wasn’t sure what I would capture.

At that point I was becoming very aware of the difference between “taking” pictures and “making” pictures. You’re not just out in the open, hoping to capture something. You’re making a statement. You’re saying something. But the uncertainty of what my grandmother would do, that’s where it breaks into documentary work.

My grandmother was the one who gave me the idea to do self-portraits. She didn’t want to be in front of the camera, really. The images I do have are from when she cooperated. They’re kind of haunting because she was a guarded, stern woman who didn’t take any nonsense. She protected me from a lot of things.

Like Detroit, Braddock is in the news these days because artists have started to move there and do projects there. Levi’s, the denim company, even used Braddock in an ad campaign and you had a pretty strong reaction to that.

The whole principle is that Braddock is this idealized romantic empty pasture where people can go and seize the land and build their lives. That’s really problematic. There is a big omission there. ... Whatever privileged people want to do in Braddock, to open their studios and drink in their bars, they’re still sitting amid all of that toxicity. For me, it’s a duty to stand in the gap and advocate as an artist for the displaced, working-class people. I know it’s not the image they necessarily want to project.

I pick up my camera very much in the spirit of Gordon Parks. He said: “I picked up a camera because it was my choice of weapons against what I hated most about the universe: racism, intolerance, poverty.”

And you made a video in response to the Levi’s ad (some of which is embedded in this post).

When I saw the commercial, it was like 2010. It was part of this “Go Forth” campaign for Levi’s by [the ad agency] Weiden Kennedy. And in it, Braddock becomes the poster child of the romanticized post-industrial town. The slogan was something along the lines of, “Everyone’s work is equally important. We are all workers. Go forth.”

People think of towns like Braddock as post-industrial, but they’re not. Braddock has 300 sprawling acres of industry of steel, if not more. There are people who are still getting up and going to work every day at the mill. So this other narrative is deceiving.

I’m seeing all of those images around New York City and I’m thinking, how do I thwart this? So I call up my good buddy [the video artist] Liz Magic Laser. We watched all of these ‘40s and ‘50s commercials about the steel industry and we started compiling the gestures people were doing in the commercials, where working men are moving all of these large steel plates around a factory. We got a choreographer to take all of the moves and [put them together for me] into a choreography in a free-flowing way. I then dressed in these Levi’s jeans called “Boyfriend Jeans” and all this stuff that workers wear, and I carried out these movements until the jeans were shredded and ripped up.

I carry Braddock in my body. I have so much metal in my blood from living in that town. My body is that town. So to go out there in front of this Levi’s pop-up shop with pictures of my hometown and they’re talking about how cool and gritty and slick it is... It was really about destabilizing the notion a consumer would have.

What are you working on now?

Well, the book was 12 years in the making, so that has taken a lot of my time. But now I’m really interested in making this a global issue. It’s about me following U.S. Steel and the steel industry’s global footprint.

Recently, I was in Hamilton, Ontario [in Canada]. There are two steel mills there. And there’s a lot of turmoil because of downsizing, but there’s still about 600 workers left. And last year, I was at the Berlin Academy and was invited to go to Eisenhüttenstadt. I got there and I felt I understood it even though I’d never been to East Germany. It’s a steel town. I understand their body language, the way they come in and out of the mill, the shape of the town.

What’s interesting is that in Germany, a lot of the old mill sites are turned into industrial parks. People go rock climbing and swinging. It’s a park. They have concerts there. But it all made me think about what I want to do in my work now, coming from a steel mill town. In so many of these places, they’re praising the infrastructures, but they’re failing to honor and commemorate the people who worked in them, who labored and died there.

Did you take pictures of these places when you were abroad?

No, I just went. I take a long time to pick up the camera. I need to understand before I start taking pictures.

What’s your ultimate aim for the book?

I think the next step is to bring more awareness about the people who are still there, who are still stuck. My mother is still stuck. Her body is falling apart. She’s so sick I can’t move her. There are other families too. I’m hoping this book can help get people on the ground: activists, doctors, civil rights lawyers. It’s not over. Now I need to make the book a weapon, just like I made my camera a weapon.

“The Notion of Family” by LaToya Ruby Frazier is available from the Aperture Foundation. Her exhibition, “Riveted,” is on view in Texas at UT Austin’s Visual Arts Center through Saturday, at the Art Building, 23rd and Trinity Streets, Austin, utvac.org.

Find me on Twitter @cmonstah.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.