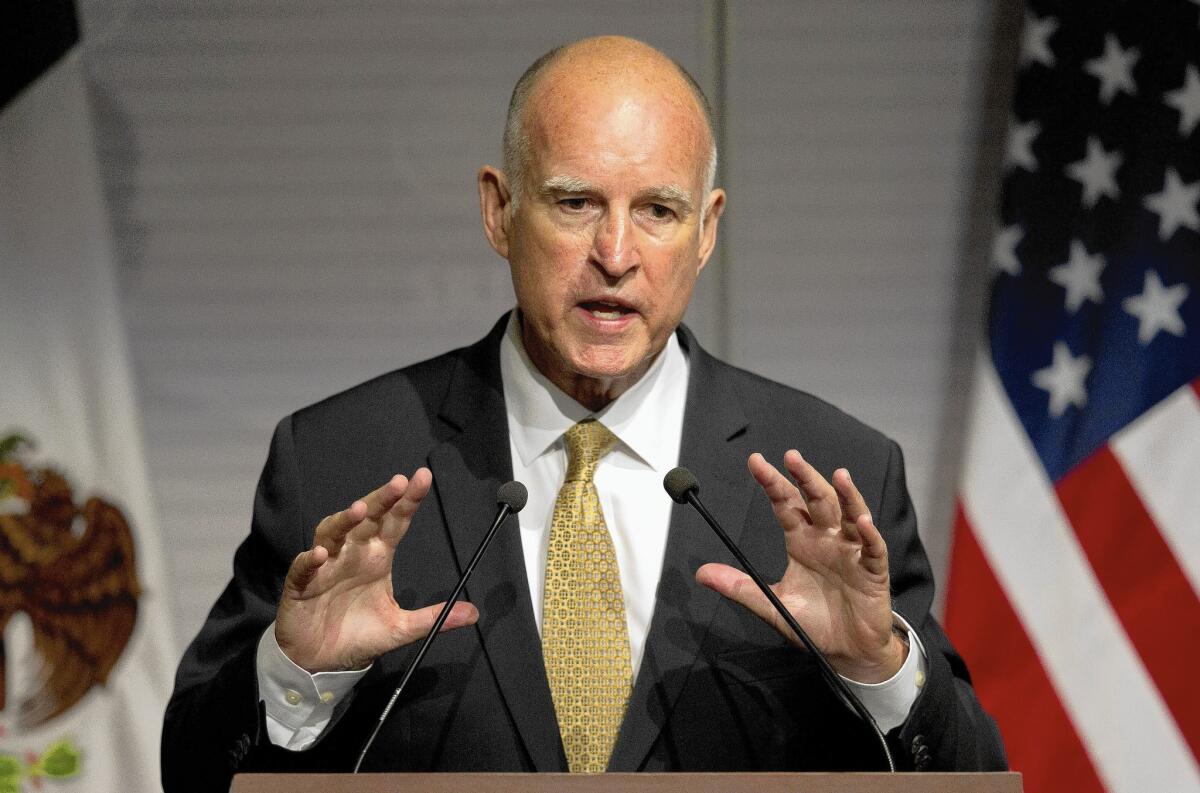

Analysis: Free of repercussions, Brown confounds friends and foes on bills

- Share via

SACRAMENTO — Gov. Jerry Brown waded through many hundreds of bills last month in the political freedom that comes with a faint reelection challenge, a $22-million campaign war chest and a Legislature stacked with fellow Democrats.

The governor dispensed gifts — and lumps of coal — to labor, business, good-government advocates and his allies in the legislative leadership. Some of his actions confounded admirers and critics alike.

Widely viewed as a shoo-in for a historic fourth term in November, the 76-year-old governor made good on his promise to keep California in the lead on immigration issues.

With his chicken-scratch signature, he expanded rights for immigrants who are in the state illegally, providing more college financial aid, for example, and easing the path to practitioners’ licenses for a wide range of professions.

Brown used his veto pen to lecture Democratic leaders on the continued need for fiscal discipline, striking hundreds of millions of dollars meant for college campus repairs and a share of state vehicle license fees for newborn California cities.

Yet he loosened the purse strings to give a five-year, $330-million tax break to Hollywood and, earlier this year, steamrolled the Legislature into diverting hundreds of millions of dollars in polluter fees to the high-speed rail system he champions.

“Absent any real pressure from interest groups, absent any White House aspirations, absent any real pressure from his loyal constituency, he could be a free agent during bill signing,” said Bill Whalen, a fellow at Stanford’s Hoover Institution who was a speechwriter for former Republican Gov. Pete Wilson.

Conservatives bristled at the governor’s approval of the nation’s first statewide ban on plastic grocery bags. But attempts to dismiss Brown as a nanny-esque liberal were tempered when he vetoed mandatory diaper-changing tables in men’s restrooms, cautioning against over-regulation.

And despite the looming election, when some partisan politicians contort themselves to play to voters, Brown vetoed major policy changes coveted by the Democratic Party’s most powerful supporter — labor unions.

The governor torpedoed legislation that would have required mediation for farm labor disputes, pushed by the United Farm Workers of America. He approved a groundbreaking measure requiring three paid sick days for workers in California, but displeased the Service Employees International Union by insisting that the home health aides it represents be excluded.

Some labor officials were conciliatory about the matters, at least publicly — further evidence of Brown’s strength in Sacramento.

“Of course, we are disappointed with his veto …, but we are pleased with the progress we made in recent years and grateful for his support,” said Luz Pena, United Farm Workers communications coordinator, who praised Brown’s aiding of immigrants.

Brown also rejected bills promoted by Democratic leaders. He vetoed anti-truancy legislation that was a top priority of Atty. Gen. Kamala Harris, whose aspirations tor higher office are widely assumed.

The governor also rejected $100 million for deferred maintenance at UC and Cal State campuses, funding pushed by Assembly Speaker Toni Atkins (D-San Diego). Brown said it would be unwise to spend so much money when “we are facing unanticipated costs such as fighting the state’s extreme wildfires.”

Incoming Senate President Kevin de León (D-Los Angeles) also took some sharp elbows. Brown vetoed his bill to overhaul the state’s process for permitting hazardous-waste facilities, a response to the public uproar over pollution from Exide Technologies’ battery recycling plant in Vernon, in De León’s district.

The governor also rejected De León’s bid for new restrictions on gifts for elected officials in response to three Democratic senators facing jail time, two of them over political corruption allegations. Brown’s veto message said current gift disclosure laws “should be sufficient to guard against undue influence.”

In his veto Tuesday, Brown referred to a 1964 article by his former law professor to bring “clarity” to the issue. On Wednesday, De León pushed back.

“I’m happy to read an article recommended by the governor from 50 years ago,” De León said in a statement, but state political laws “should reflect today’s interests and values, and that includes not taking gifts from lobbyists.”

Evan Westrup, Brown’s spokesman, said the vetoes have not affected the governor’s relationship with De León, noting that he has signed more than 30 of the senator’s bills since taking office — including many of De León’s top legislative priorities. Brown has done the same with Atkins and other Democratic leaders.

“Each bill is assessed on its own merits. That’s issue-based, not person-based,’’ Westrup said. “The governor is not making decisions based on politics alone.”

Robert Stern, a onetime Brown aide and longtime advocate for stronger ethics laws, said he was dismayed to see the governor — who helped craft California’s 1974 Political Reform Act — dismiss so many ethics bills this year.

Along with the gift restrictions, Brown vetoed measures that would have barred elected officials from using campaign funds for clothing, vacations and donations to nonprofit groups run by their family members; limited campaign contributions to water board members; and prohibited school administrators from donating to the campaigns of school board members that oversee them.

“As usual,” Stern said, “he is very unpredictable.’’

Twitter: @philwillon @mcgreevy99

Times staff writer Melanie Mason in Los Angeles contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.