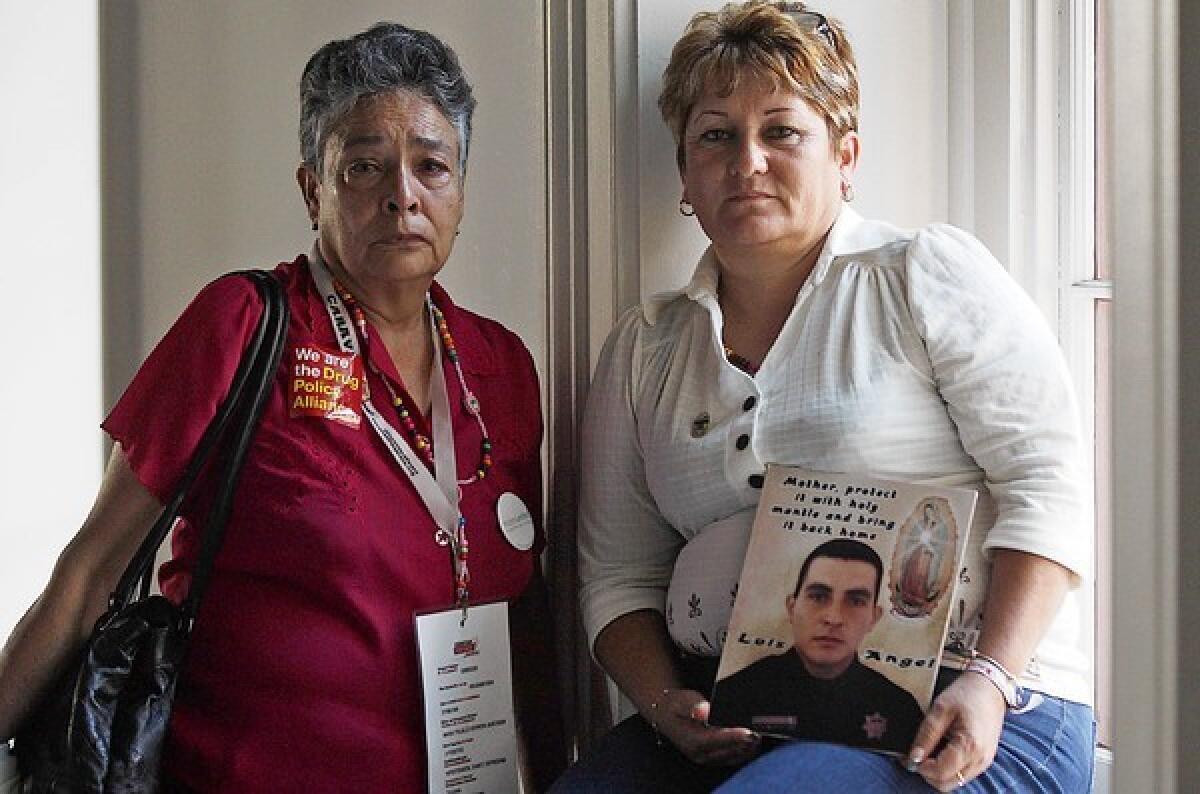

Mothers share their anguish at losses to Mexico’s violence

- Share via

Araceli Magdalena Rodriguez remembers precisely when her son first said he wanted to be a policeman. She went to the market one day in their community near Puebla, Mexico, when he was 4 years old and returned home empty-handed after a pickpocket stole her wallet.

“Where are my bananas?” Luis Angel Leon Rodriguez asked his mother.

When she told him what had happened, the boy said he would grow up to be a police officer and catch the thief.

Nearly 20 years later, Luis Angel became a federal police officer, but when his mother told me the story Monday afternoon on a visit to Los Angeles, she was in tears. In November of 2009, Luis left with six other officers for a posting in the state of Michoacan, but they never arrived at their destination.

What Araceli Rodriguez discovered three months later, after being stonewalled by authorities and receiving anonymous threats on her life, haunts her to this day. Authorities told her that organized crime figures intercepted her son and his comrades, ordered them to cooperate with their drug cartel and executed them when they refused.

“They said the way they killed them was with a shot to the head,” said Rodriguez, who held a photo of Luis Angel as she spoke, as if that might give her the courage to continue the story. “They cut up their bodies with a chain saw,” she said, and tossed the parts into a vat of corrosive chemicals. “They said, ‘They are dead, but you will never find their bodies.’ ”

Rodriguez, on leave from her job as a restaurant hostess in Mexico City, came to Los Angeles with several dozen of her countrymen, all of whom had been touched by drug violence, to speak out about “the nightmare we are suffering in Mexico.” Led by Mexican poet Javier Sicilia, whose son was murdered last year, Caravan for Peace will travel east over the next month, stopping in many cities on the way toWashington, D.C., with tales of heartbreak and loss.

I spoke to three mothers, each of them crushed by grief and motivated by a desire to give faces and names to statistics. With an estimated 50,000 people killed or missing in the last six years of drug violence, they said corruption and greed in Mexico have ruptured the soul of the country. But they also said many of the weapons used to create rivers of blood and towns full of ghosts are manufactured in the U.S., and that our craving for drugs has filled cemeteries in Mexico.

Their greatest hope, though, is to appeal to the consciences of fellow human beings by telling stories. After hearing their stories, I had a number of questions.

Why do we use our failures in the drug war to justify even more investment in failed strategies?

Given the unstoppable supply of drugs, wouldn’t it make more sense to wage war on the demand?

Would there be anywhere near as much carnage in Mexico — or any greater drug abuse in the U.S. — if drugs were legalized and regulated, with the savings from interdiction plowed into prevention and treatment?

Maria Trujillo Herrera came to Los Angeles with a poster displaying the images of her four sons, all in their 20s and working in metals salvaging. Raul and Jesus went missing in August 2008 while on a business trip to Guerrero, and Luis and Gustavo never returned from a trip to Veracruz in September 2010.

It’s impossible to know what happened to them, Herrera said. And if she ever does find out, the news will probably be grim given the level of savagery on the part of the cartels.

Herrera said the people she has met include “doctors, ecologists, lawyers and nurses” who have lost their children. “And they have disappeared, with no reason and without a trace.” Herrera wants to believe, she said, that her sons are still alive.

“I will keep on looking until I die,” Herrera said, her chest heaving and tears streaming as she told of her sons’ wives and children, all of whom have moved in with her to bolster one another’s spirits and keep a candle burning. “If my sons are listening to me, I want them to know I love them, that I need them.”

When I was finished talking to Herrera, one more woman was waiting for a chance to talk to me. Margarita Lopez Perez was carrying her daughter’s wedding photo, taken a year and a half ago, when Yahaira Guadalupe Bahena Lopez was a beautiful, dark-haired 18-year-old. Yahaira and her husband, a federal police officer, moved from Michoacan to Oaxaca, where he had been reassigned. One night, when her husband was on duty, armed gunmen kidnapped Yahaira from her home.

Perez said her search for her daughter has resulted in multiple threats against her, including from authorities. There is corruption at every level of government, she said, and she has worn disguises to avoid detection while trying to crack the mystery of her daughter’s disappearance.

“Every day, I risked my life,” said Perez, who was composed until she told of visiting morgues and grave sites and seeing countless corpses, many of them young women’s, and many of them beheaded.

“I’ve seen hundreds of bodies,” she said. “Bodies piled up, decomposing. Bodies in unrefrigerated rooms of morgues.”

Police told her they’d found her daughter’s body, then showed her the decapitated head of a young woman.

“Those were not her teeth,” Perez said, but police told her that if she didn’t accept their insistence, she and the rest of her family would be at risk.

Her amateur detective work led her to criminals with a cartel connection, who told her that her daughter had been abducted because she was suspected of having ties that the kidnappers hoped to exploit. Perez’s daughter insisted otherwise even as she was tortured nearly to death. She was then raped, the sources told Perez, and decapitated, and even then, further defiled.

“My soul hurts,” said Perez, who moves constantly from one place to another in Mexico because she fears being killed for speaking up. “I cannot breathe without thinking about my girl. Help me. Help me to let people know what’s happening.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.