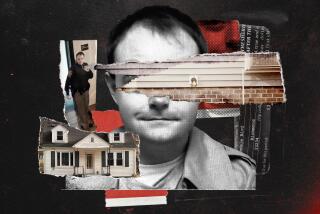

Girl who went missing in 1961 may be victim of serial killer Mack Ray Edwards

- Share via

Nearly 50 years ago, a 7-year-old girl named Ramona Price took a Saturday morning stroll down a quiet lane on the outskirts of Santa Barbara.

She never returned — and now police think she may have encountered Mack Ray Edwards, a heavy-equipment operator who is believed to have killed as many as 20 children before he confessed to six murders and hanged himself in his San Quentin prison cell in 1972.

On Wednesday, cadaver dogs will scour the area around a bridge spanning the 101 Freeway at Winchester Canyon Road. Edwards — who was described by his Sylmar neighbors as a “quiet, very nice guy” — worked on that bridge around the time Ramona vanished in 1961.

Photos: 2008 search for another victim

Edwards’ monstrous legacy is still unfolding. Three years ago, authorities excavated an exit ramp off the 23 Freeway in Ventura County, seeking the bones of 16-year-old Roger Dale Madison of Sylmar. Edwards, a neighbor and friend of the Madison family, had admitted stabbing the boy near the freeway when it was under construction in 1968. He worked on that project too, and authorities believe the boy’s body may be buried beneath the roadway. After five days of digging, police called off the search.

At a news conference Wednesday morning, Santa Barbara Police Chief Cam Sanchez is expected to identify Edwards as a possible suspect in Ramona’s death.

Officials caution that it’s only a possibility — but one bolstered by Edwards’ work on the bridge and the fact that he temporarily lived with a friend just a quarter-mile away. The bridge is being reconstructed now, which makes it an ideal time to investigate the site, officials said.

“The big thing is for us not to miss this opportunity,” said Santa Barbara police cold case investigator Jaycee D. Hunter. “We would be stupid not to do it.”

Police in Santa Barbara, Los Angeles, Pasadena, Torrance and other areas where children went missing while Edwards was at large have been trying to nail down his trail for years.

“We can’t give up finding these kids, we just can’t,” said Los Angeles police Det. Vivian Flores. “These children represent your kids and my kids. Would you ever want detectives to stop looking if your child was missing?”

For decades, there were no clues in Ramona Price’s disappearance. But four years ago, Pasadena author Weston DeWalt, who is writing a book on the Edwards murders, asked Santa Barbara authorities for permission to review their files.

Last year, he showed Santa Barbara investigators records he’d unearthed indicating that Edwards was employed by a highway contractor that did work in Santa Barbara. He found the friend Edwards had roomed with and, at the request of police, contacted Caltrans officials about the possibility of excavating a site where Edwards had worked.

DeWalt was out of the country Tuesday, looking for shipwrecks off Poland.

If cadaver dogs detect the presence of remains, police said excavation could begin next week.

“We have to make some battlefield decisions on some things,” Hunter said.

Edwards exhibited a strange blend of solicitude and cruelty.

In 1970, he and a 15-year-old accomplice botched an attempt to kidnap three young sisters in Sylmar. When Edwards turned himself in to the police, he gave a startled sergeant his gun and cautioned him to be careful because it was loaded. When he pleaded guilty to three of the murders, he was disappointed that relatives would have to sit in court and hear the agonizing details of their loved ones’ deaths.

But his crimes were extraordinarily brutal. In 1953, he kidnapped 8-year-old Stella Darlene Nolan, molested her, strangled her and threw her off a remote bridge. When he returned the next day to find the Norwalk girl was still alive and had crawled 100 yards, he stabbed her and buried her in an embankment that became part of the Santa Ana Freeway.

That was his first known killing. He pointed police to her body in 1970.

When Ramona Price disappeared in Santa Barbara on Sept. 2, 1961, authorities quickly focused on a pair of brothers who had been convicted of sex crimes. The brothers were given lie-detector tests and “truth serum,” but there was not enough evidence to prosecute them.

Edwards pleaded guilty to the murders of Stella Nolan, 13-year-old Donald Allen Todd Jr. of Pacoima, and 16-year-old Gary Rocha of Granada Hills. He mentioned to inmates and a Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputy that he had killed others, though his numbers varied. Before investigators could get to the bottom of his claims, he strangled himself with a TV cord.

He had said he was eager to face the death penalty and tried to commit suicide in custody twice before.

The motives for his lengthy rampage remain murky. He molested some — but not all — of his victims. In court, he expressed no sympathy for them despite his concern for their families.

Asked by an investigator why he did it, Edwards was enigmatic.

“Why does anyone do it?” he said.

Photos: 2008 search for another victim

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.