Opinion: Justice Antonin Scalia (yes, Scalia) rules for a criminal defendant

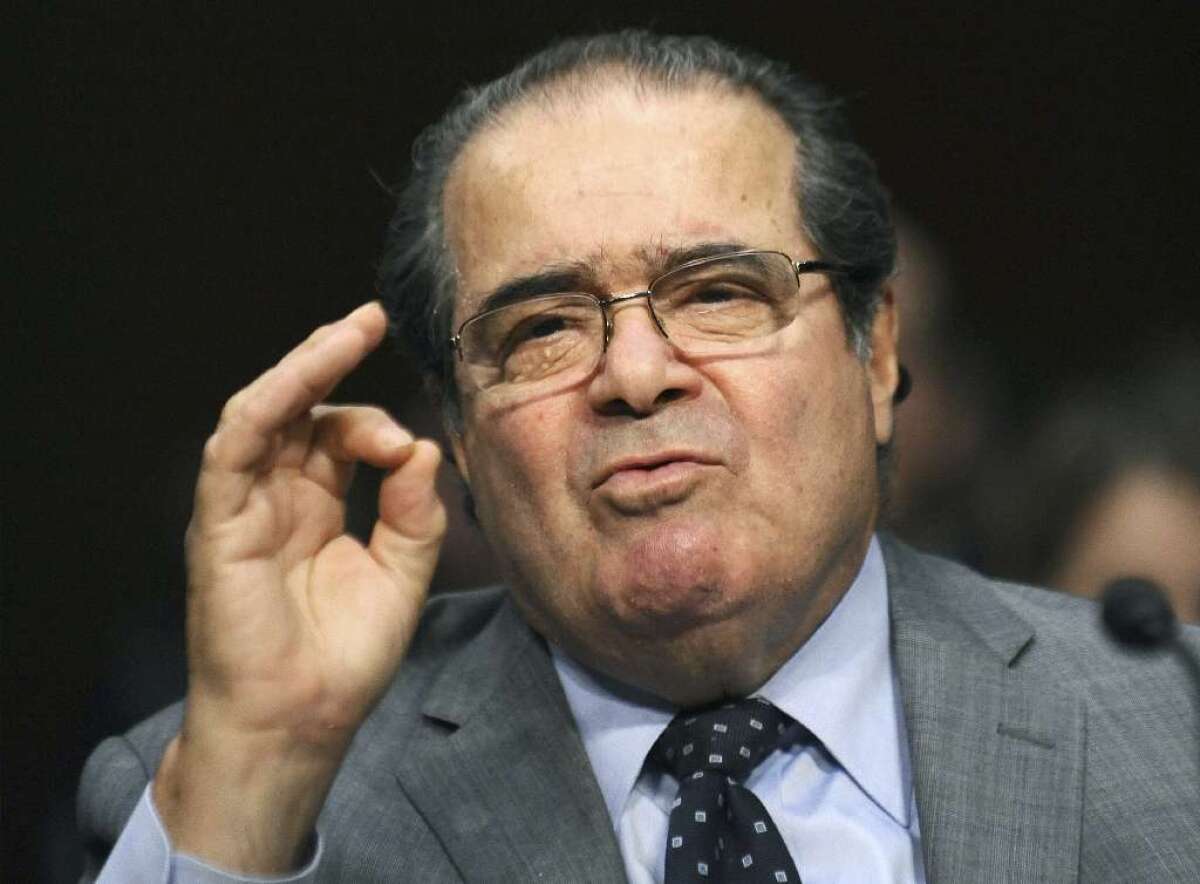

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia.

- Share via

Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia has received a lot of criticism for his scabrous dissenting opinions in the same-sex marriage and Affordable Care Act decisions. (Some comedians have even turned Scalia’s dissents into a song.)

But Scalia is entitled to some love for his majority opinion in a decision that has been overshadowed by the marriage, ACA and other blockbuster rulings. In Johnson vs. United States, handed down on the same day as the marriage case, the court by an 8-1 vote overturned the sentence of Samuel Johnson, a white supremacist who was arrested after telling an undercover FBI agent that he had homemade explosives and had picked out several targets. He was found with an AK-47 rifle and a .22 caliber semiautomatic handgun.

Under the Armed Career Criminal Act, Johnson was sentenced to a 15-year prison term because he had three prior “violent felonies” on his record. Johnson conceded that two of his previous convictions, for robbery and attempted robbery, were violent felonies. But he disputed the government’s decision to classify a third conviction, for possessing a short-barreled shotgun, as a “violent felony.”

Writing for himself and five other justices, Scalia said that the provision under which Johnson received his enhanced sentence was unconstitutionally vague.

The Armed Career Criminal Act defines a “violent felony” as “any crime punishable by imprisonment for a term exceeding one year ... that — “(i) has as an element of the use, attempted use, or threatened use of physical force against the person of another; or “(ii) is burglary, arson, or extortion, involves use of explosives, or otherwise involves conduct that presents a serious potential risk of physical injury to another.”

The problem was with the last clause: “conduct that presents a serious potential risk of physical injury to another.” For years, courts have been struggling about what that means. Does it cover drunken driving (which could, but usually doesn’t, result in death)? How about fleeing the police?

Scalia, who long has raised concerns about this provision, concluded that it violated the 5th Amendment’s due process clause, which, he noted, prohibits the government from “taking away someone’s life, liberty, or property under a criminal law so vague that it fails to give ordinary people fair notice of the conduct it punishes, or so standardless that it invites arbitrary enforcement.”

The notion that laws should give notice about what they forbid is a longstanding one (and in some tension with another principle, that ignorance of the law is no excuse). But Scalia’s willingness to invoke it in this case is a reminder that he often rules for criminal defendants, including in search-and-seizure cases and those involving the right to confront one’s accusers in court.

But those opinions get less attention that his dissenting views. And don’t expect to hear the majority opinion in Johnson vs. United States set to music.

Follow Michael McGough on Twitter @MichaelMcGough3

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.