‘I Don’t Change No Words and You Can Quote Me’

- Share via

In boasting recently that I would never knowingly misquote anyone, whether a waitress or an emperor, I failed to consider one possible exception.

What provoked my testament of purity was a federal appeals court ruling that a journalist may alter or fabricate quotations from public figures provided the fabrications reflect the essence of what was actually said.

Harrison Stephens of Claremont, himself a former reporter, writes that he generally kept my ethical standards, but he sometimes made exceptions when quoting someone who misused a word or used bad grammar.

He recalls a public figure who consistently said “in lieu of” when he meant “in view of.” Stephens says: “Surely accuracy doesn’t demand that I quote his wrong word and then state parenthetically what he ‘evidently’ intended. Or does it? (I never did.)”

I have been faced with that dilemma too. Usually, like Stephens, I have corrected the error, to spare its author a pointless embarrassment, rather than quoting it and tagging on that supercilious sic .

One would hope, though, that Stephens’ subject, who evidently made the same error over and over again, would see it corrected in print and sooner or later get the message.

There are two exceptions to this policy. One is in the case of a person who has written me to correct my grammar, meanwhile flubbing one himself. Then I am only too happy to quote his own goof.

The other is when the quote is so characteristic of the person quoted that to correct it would be to destroy his personality. Stephens also makes that point.

“Only a cretin,” he says, “would destory the music of one of Sparky Anderson’s multiple negatives.” For example, he quotes: “It don’t take no genius, Vinnie, to figure that no pitcher’s gonna throw no lollipop to no Mike Marshall when he’s on a hot streak.”

Indeed, to substitute “It doesn’t take any genius” for “‘It don’t take no genius” would be no service to Sparky Anderson, and no service to the language.

Even the respectable Bartlett’s Familiar Quotations preserves the complaint of fight manager Joe Jacobs after Jack Sharkey was given a decision and the heavyweight title over Jacobs’ man, Max Schmeling. “We wuz robbed!” yelled Jacobs into a microphone, coast to coast.

Later Jacobs got up from a sick bed to attend a World Series game between Detroit and Chicago. He bet on Chicago; Detroit won. Jacobs said, “I should of stood in bed,” thus giving the language an imperishable phrase.

Any reporter who would change either of those quotes into good grammar is in the wrong business. Arthur R. Vinsel, also a former newspaperman, shares that prejudice. “I used to go wild at a daily in Orange County when editors would transform the wonderful colloquialisms of a colorful character into proper English because we posed as a dignified family newspaper.”

What reporters would have been foolish enough to change Casey Stengel’s convoluted syntax into standard English? This is Stengel, as quoted by Jim Murray in his book, “The Best of Jim Murray”: “But now you look over at that other league and there is this Pepperoni (editor’s note: Joe Pepitone) nobody knew who he was till the day before yesterday or how to pronounce his name and I got some men who are unknown too, but I was saving my pitcher until I got ahead in the seventh inning, but I never got ahead and I said to my other pitcher that I better take him out, people were beginning to talk.”

On second thought, no reporter could reduce Stengel’s monologues to faultless syntax.

And how can we repay Yogi Berra for his contributions to the language? It was in 1973, during the National League pennant race, that Berra, then manager of the New York Mets, said: “It ain’t over till it’s over.” That, by the way, was quoted by William Safire, a newspaperman who respects the language as much as any other.

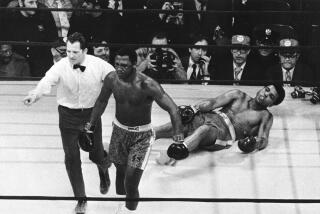

One of my favorite quotes in American literature is the one attributed to Muhammad Ali, then heavyweight boxing champion of the world, when an airline flight attendant told him to fasten his seat belt. Ali said, “Superman don’t need no seat belt.”

The only line I’ve ever heard that tops that one is what the flight attendant answered back. She said, “Superman don’t need no airplane, either.”

There ain’t no way to improve on that.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.