They’re Two of a Kind : Twins Bob and Bill White Are a Fun-Loving--and Influential--Pair

- Share via

Millie’s Country Kitchen in Norwalk has a historical motif, with photos of horse-and-wagon street scenes and the city’s first barbershop. One picture, taken more than 40 years ago, shows two similar looking men in baseball uniforms.

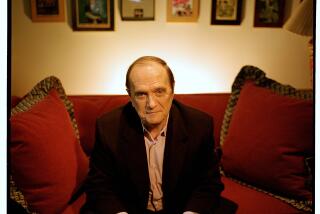

Beneath that wood-framed memory, the same men sat on a recent morning--twins Robert E. White, a veteran Norwalk councilman, and William A. White, a member of the Norwalk-La Mirada Unified School District board.

“We were the first professional ballplayers out of here,” Bill White said, glancing at the photo from their days in the minor leagues.

Huge and towering at age 71, dressed now in ties and blazers, they filled an orange booth.

Topping 6 feet 6 and weighing more than 275 pounds, they have loomed over Norwalk as athletes, teachers, politicians and song-and-dance men, savoring their reputations as down-home, fun-loving characters.

“We were always out in front because of our size,” said Bob White, his voice loud like his brother’s. “We’ll walk into a place now and the maitre d’ will come up and say, ‘Are you guys here to film a beer commercial?’ ”

With a large, thick hand, Bill signaled across the restaurant. “Hey, waitress, can we order, honey?”

“You know what, Bill,” Bob said, consulting a menu. “I had a doughnut, but I wouldn’t mind having whatever their special is, just to get by.”

“OK,” Bill said to the waitress. “Scramble the eggs. Bacon crisp. Potatoes. And I’ll have whole wheat bread.”

“Me too,” said Bob.

The Whites grew up on Sycamore Street when Norwalk, now with 94,000 people, barely had 3,000. “You should have seen Norwalk in the old days,” Bob joked. “Every time a train would come in town they’d go out and look at it ‘cause they didn’t know when they’d see another.”

They inherited their knack for storytelling from their father, an Arkansas native who had a little food store and soda fountain near Metropolitan State Hospital in Norwalk and brimmed with expressions such as “happier than a dead pig in the sunshine.”

Thomas Benton White was also a good provider. “We had a perfect family life,” Bob said. “We always had a good suit to wear to Sunday School. Some kids had to go home and milk cows; Bill and I were lucky.”

At Excelsior High School on Alondra Boulevard, Bill played left end on the football team, and Bob played right end. They were skinny then, especially Bill. “I could drink a bottle of strawberry pop and look like a thermometer,” he recalled.

They played baseball at USC and then served as Coast Guard shipmates from 1943 to 1945 before starting long minor-league baseball careers, Bill as an outfielder, Bob as a first baseman.

After realizing in the early 1950s that they were not going to make it to the New York Yankees, they took up teaching careers. Bill taught for 28 years at Huntington Park High School, and Bob taught for more than 30 years, first at Washington High in Los Angeles and then South Gate Junior High. Both coached baseball and basketball.

“I’m glad we retired when we did,” Bill said. “When corporal punishment went out, it took away a lot of the discipline, the old paddle in the gym. We used to give a kid an option of taking a swat or calling his mother. He usually took the swat.”

The behavior of students still upsets him. “Look at graduation ceremonies, they’re pitiful,” he said. “They throw balloons and do the wave.”

Bill has been on the Norwalk-La Mirada school board since 1981. “I’ve kept my finger in the pie of education,” he said. “I think every school board should have a retired teacher on it.”

Bob entered politics in 1958, winning a seat on the now-defunct Southeast Parks and Recreation District board. “I was a frustrated showboat who loved to be in charge,” he explained.

He decided to run for City Council in Norwalk 10 years later, and was elected on his first try. He ran for Congress as a Democrat in 1974, losing to Del Clawson, and for the state Assembly in 1984, losing to Wayne Grisham. Both times he got 42% of the vote.

Georgia Gov. Jimmy Carter tried to bolster Bob’s congressional campaign in 1974.

“He came out to Norwalk and knocked on doors for my brother,” Bill said, knocking on the table at Millie’s. “This is the way his speech went, you know how he talks: ‘My name is Jimmy Cahter. Georgia. ‘Preciate very much if you vote for Bob White. He’s a fine fella.’

“Then he’d give ‘em a package of peanuts because he’s a peanut farmer, you know. Oh, it was cute.”

The only noticeable differences in the twins today is that Bob has a fuller face and weighs 300 pounds, 25 more than Bill.

When Bill, who lives in La Mirada, comes to Norwalk, he naturally is mistaken for his brother.

“They’ll see him at a bank and ask what he intends to do about crime or street lights,” said Bob with a laugh. “And he’ll say, ‘Well, we’ve got a committee on that right now.’ ”

At Excelsior High, Frances Neal, Bob’s sweetheart and eventual wife, could tell them apart because Bob’s shoes were brown and Bill’s were black. A draft-board doctor a few years later had no such clue.

“In World War II, Bob took my physical,” Bill said. “He’s 6-7 and I’m 6-6 1/2. If you were 6-7 you were 4-F, so I would have had to go. Bob went first, and when he came back I told him to walk around me and do it again. We had the same color shorts on.”

Bob broke in sheepishly: “For the longest time we didn’t want that known ‘cause that’s not the right thing to do.”

But within two years they had begun their Coast Guard service.

During Norwalk City Council meetings, Bob sits on the extreme right of the chamber because he does not hear well in his right ear. Even if his hearing were perfect, he knows he should be on the right.

“I’m very conservative,” he said. “I like to help people, but we’re giving people too much these days. I don’t go along much with all these damn frills and amenities.”

He talks excitedly about Norwalk’s commercial growth, but consistently opposes efforts to bring in outside consultants to study the city’s problems. And he does not apologize for longing for a vanished era: “I was much happier when times were simpler in Norwalk.”

His folksy, nostalgic bent does not set as well with other councilmen at meetings as it used to. Often he is cut off during one of his what-Norwalk-used-to-be-like stories.

“In the old days I would have no problem getting three votes on something I brought up,” Bob said. “Now it can be a lonely night when I’m outvoted, 4-1. Somewhere along the line I must have ruffled some feathers.”

But his colleagues are reluctant to criticize him. “Call someone else,” Councilman Luigi A. Vernola said last week when asked how he felt about Bob.

Mayor Mike Mendez said: “I think he cares a lot about Norwalk and is trying to do his best for the city. He’s a real character, a really nice guy.”

The councilman expects to win a seventh term in April. “I’m like an old shoe,” said Bob, who has won his first five races easily. In 1988 he led seven candidates, getting 600 more votes than runner-up Mendez, who also was elected.

Inseparable most of their lives, the twins still get together three or four times a week. Bill is divorced. Bob has been married to Frances for 48 years.

“It seems like when Bob’s wife is away at bingo, he’ll call and say, ‘I got some soup on the stove, Whitey, come over and watch the ballgame,’ ” Bill said.

“We are so close that we’ve talked about how when one of us goes, breaking up the act, how tough it will be on the one left. But with me a bachelor, I’ve been alone a lot, so I could probably make the adjustment better. But I hope life is good for us a couple more years. Bob and I got a lot of vim and vigor and we love to go out and sing.”

They developed a song-and-dance routine riding on buses in the minor leagues. In a Nebraska American Legion hall, they would sing all night and never have to buy a drink, the piano stacked with beer pitchers the customers would buy for them.

They still perform at picnics and retirement parties. “Sometimes we bomb,” Bill said, “especially when the crowd’s been drinking.”

After they left Millie’s on that recent morning, they drove a block to City Hall, and, outside the dome-like council building, broke into their act.

Bill strummed his ukulele as they harmonized:

“I will be your rooster, honey, if you will be my hen.

I’ll come over and see you honey every now and then.

I ain’t gonna allow no other chickens in my yard but you.

Say ol’ hen whatcha cluckin’ about, say honey I love you.”

People walking nearby stopped, including a young man, who watched with amusement and surprise, these rural rhythms foreign now in a city that moves to a Latin beat.

The big men, their ruddy faces perspiring, went on to the next verse. They looked as happy as, their father would have said, dead pigs in the sunshine.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.