Stone-Faced and Awed

- Share via

O, sweet red rock!

When we first see Chimney Rock through the morning fog, it looks like an enormous “welcome home” sign. With so many of us on the wagon train being Westerners, there’s a part of us reserved to hold a love of red rock and sagebrush and all things dry and desolate.

Chimney Rock is the first rock formation we’ve seen since leaving home months ago. For the original pioneers, this rock had great significance, as it marked the halfway point in their journey. Renderings of its shape appear in many pioneer journals.

After months of grass, dirt, sand and mud, most of us are eager to get our hands and feet back on rock.

After reaching camp, we pile into a vehicle to see something marked on the map as Natural Bridge. And when we come through the gate and look around, we see, tucked down there in a hollow between dry small hills, a stream flowing through red, red rock.

There are shouts of “Stop the car, stop the car!” as a sheer cliff of rock looms in front of us. We run across the grass and all but embrace the stone facade. There are tears in the eyes of some who have been raised in the canyons of the West and haven’t realized how much they miss home.

For the Easterners, seeing the sweep of sandstone and the way the water runs through it is a revelation. The landscape mutates by the minute as the position of the sun changes to highlight the swirls and arches on the face of the cliffs and bluffs.

We stay as long as we can--which is until the ranger chases us out to close the gate.

What a glorious jolt Natural Bridge is for us. I feel like I’m breathing easier now that I’m in land that knows me. After the horrendously high mileage we’ve been covering lately (between 27 and 30 miles daily) we’re on the brink of discouragement. But seeing and touching and climbing on the rocks of the West somehow soothes us.

For our ancestors, I’m sure that geography like this was more frightening than comforting. I can imagine watching them 150 years ago as they stared at the starkness of this country, wanting to turn back to the green fertile fields of the East. I like to picture modern-day trekkers looking on from the sidelines and whispering, “Keep going and stick it out--your grandchildren are going to love this!”

I suppose our love for the deserts of the West is explained in the adage that “you don’t serve the ones you love, you love the ones you serve.” Or, as Jan Pierce, our registration coordinator says, “That’s why we love our children and our dogs--they need us so much that we’re slaves to them, and they can’t do much in return.”

The land in the West has to be served. It has to be slaved over and sweated over and cursed and kicked before it yields a livelihood.

We can’t plant and let rain do the rest. We can’t go hiking and expect to find water and shade and lawn to lounge on. The West doesn’t have much forgiveness in it, as far as the land is concerned.

But because of the physical and emotional investment required for living on this kind of land, it owns us, rather than the other way around.

From Chimney Rock to Register Rock to Independence Rock to Split Rock and onward we move, pulling our carts.

In Nebraska we walked across land with no natural landmarks. Now we walk from rock to rock, and we can see in the morning the landmark we’ll be camping near for the night. It makes us feel like we’re going somewhere, because we can see destinations before and behind us.

The pioneer travelers had far less certainty. They did not know how far they would travel, or how long it would take. The scouts rode a day or two ahead to find water, grass enough for the animals and the best route. Today the best route has long since been mapped out.

As we travel through Wyoming, we are cradled in valleys between mountains on the south and rock hills on the north. It feels as if we’re being channeled along the trail by outstretched arms of rock that protect us as we walk homeward.

* Kathy Stickel, 27, of Huntington Beach is filing periodic reports from the Mormon Trail Wagon Train, which is retracing the 1,000-mile route of the Mormon migration from Iowa to Utah 150 years ago.

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

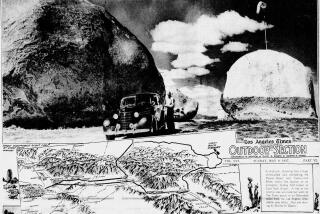

The Mormon Trail

To mark the 150th anniversary of the Mormon migration to Salt Lake City, hundreds of people on foot and in wagon are retracing the route this spring and summer. The travelers are more than halfway through the 1,000-mile trip, which began in Council Bluffs, Iowa, in late April.They expect to reach Salt Lake City on July 22.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.