Little League Losing Its Grip on Kids

- Share via

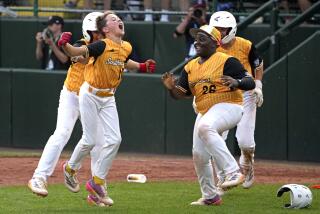

A summer ritual will unfold next week in Williamsport, Pa., when the 58th Little League World Series gets underway. Sixteen teams from nine countries will compete for the most prestigious championship in youth sports.

But in the United States, where the game was born, fewer young people will notice. Coaches and youth sports organizations say a lot of American kids are losing interest in baseball.

“Every year, it gets tougher and tougher to keep kids on the field,” said Mike Hirschman, administrator of the Little League in Northern Delaware that appeared in last year’s World Series. Even with that success, Hirschman has struggled to recruit players.

“It’s really getting disheartening,” he said. “I don’t think Little League will ever fade away. But ... kids are just spread so thin. There’s so many more options.”

Some youngsters are lured by the speed and individual glory of such extreme sports as skateboarding, inline skating and stunt bicycling. Others are riveted to their chairs by computer games, including some that simulate real baseball games.

And many are simply choosing other team sports with more action and faster play. Once America’s signature sport, amateur baseball now ranks sixth behind basketball, soccer, softball, football and volleyball in number of players, most of whom are youths, according to the Sporting Goods Manufacturers Assn.

Since 1987, when amateur baseball attracted more than 15 million players, the number has plummeted 27%, while soccer, ice hockey and lacrosse are swelling with new players.

This is not to say baseball itself is suffering. Major league baseball is thriving, with attendance up 10% over last season. And travel ball, baseball played by youths who go on the road to compete, also is growing in popularity, siphoning talented players away from Little League.

But the kind of baseball played on urban sandlots and glossy suburban diamonds since early in the last century is fading.

The effects are most obvious in Little League, an association of baseball teams in various age divisions for boys and girls 5 to 18 that guarantees all participants time on the field. It was the training ground for major league stars Tom Seaver, Doc Gooden and Gary Sheffield -- and a rite of passage for American boys.

Little League was born in 1938 when oil company clerk Carl Stotz in Williamsport, Pa., worried that his nephews were too young to play organized baseball. Stotz created a three-team league. By 1949, the league had grown to 309 teams. This year, league officials say, more than 2.2 million kids will play on about 12,000 fields in 76 countries.

Outside of the United States, participation has been steady at about 100,000. But within the U.S, nearly 300 leagues out of more than 6,400 have folded in the last seven years. Participation has dropped about 40,000 -- nearly 2% -- annually for six consecutive years to about 2.2 million players in 2003.

Typical is Orange County’s North Sunrise Little League in Orange, which, after a decade of growth, has lost seven teams and 15% of its player base in two years. This was occurring as the major league team down the street, the Anaheim Angels, was winning a World Series and becoming one of the game’s top draws.

“It’s hard to make baseball look glamorous,” said Orange resident Shawn Harper, whose 9-year-old son, Bryce, plays for the Little League Mets, “especially next to a guy going 60 feet up in the air on a dirt bike or to [skateboarder] Tony Hawk flying 10 feet through the air off a vert ramp.”

Tyler Brown, 14, said he is one of several in his Tustin neighborhood trading in his bat for a lacrosse stick.

“When I came back to baseball from playing lacrosse, everything just slowed down,” Brown said. “In baseball, you have to wait for the next pitch to happen and the batter may not hit it. If you wait around in lacrosse, you’ll probably get hit by somebody on the other team.”

None of this is lost on Little League Baseball, which last year began evaluating why its popularity is eroding and how to reverse the trend.

“It’s a significant concern to Little League and should be a concern to the sport overall,” Little League spokesman Lance Van Aucken said. “Little League has never seen a downturn in participation that has lasted this long, so we’re looking at ways to turn that around.”

The study found that Little League could stem the loss by increasing the playing time for marginal and lower-level players who were “vulnerable to giving up the sport.” Those players think coaches don’t pay enough attention to them and that their teammates neither like nor respect them, the study concluded.

In response, Little League is tinkering with some of its traditional rules. Leagues are given the option of letting everyone on the roster bat, rather than only those who are playing in the field, and leagues may increase minimum-play requirement to three innings from two, for example.

“If it can get kids out on the field, we’re going to try it,” Van Aucken said.

But many think it will take more than rule changes to reverse the decline. Among them is syndicated columnist George Will, the author of two books on baseball who serves on baseball Commissioner Bud Selig’s panel to address the sport’s future and is a member of the Little League Foundation, the group’s fundraising arm.

“When my 30-year-old son was a high school baseball player, the best athletes played baseball. Now, a lot of the best athletes play lacrosse,” Will said. “It’s faster, it’s a game of flow rather than episodes and there’s a certain amount of collision.”

Indeed, a Little League game is not always fast paced. At a recent game at Handy Park in Orange, for example, runners scurried from base to base and infielders handled sharply hit ground balls. But beyond the neatly groomed infield, four outfielders spent much of the evening inspecting blades of grass, gazing at the sky or sneaking a peek at a game on a nearby field.

There are still other reasons youth baseball is suffering. American youth culture today celebrates individual achievement, not team effort, San Jose sports psychologist Thomas Tutko said.

“Kids are very independent souls today,” he said. “They want to be responsible for their own behavior. To share the victories and the losses is very difficult for them.”

While fewer kids play baseball today, those who do are more likely to take it seriously. This is part of a larger trend toward increased pressure on young people to excel at a sport to earn college scholarships or professional contracts.

Players in travel-ball leagues -- some as young as 7 -- travel regionally for high-end competition. A relatively new phenomenon, it has grown to more than 1,300 Southern California teams in just seven years.

Little League officials lament travel ball because they say it fosters burnout, but others say the trend is inevitable.

“The keen competition among players requires full-time focus on specific sports,” said Darrell Burnett, a Laguna Niguel psychologist concentrating on youth sports. “And specialization is coming earlier and earlier for these kids.”

Officials with Major League Baseball, which attracts much of its fan and talent pool from American youth baseball, say Little League’s slump has had little effect on attendance.

“We know there are much greater diversions today for kids,” said Rich Levin, an MLB spokesman. “But our game has been around for well over 100 years and we believe it has a purchase on the soul of the country and always will. Of course, that doesn’t mean we can be complacent about our game as it relates to the youth.”

Major League Baseball is working to revive baseball in city neighborhoods, where play has dropped significantly since the late 1980s when African Americans began ditching the diamond for basketball and football. Baseball officials broke ground in June, for instance, on their first domestic youth baseball academy, a $7.5-million complex at Compton Community College.

Last year, Major League Baseball contributed $250,000 to Little League’s urban initiative program, geared toward developing and upgrading fields. The initiative has created more than 100 leagues in cities since 1989.

But that upswing in interest hasn’t been enough to offset losses elsewhere to other sports. In Tustin, for instance, youth lacrosse has expanded from 37 players to 1,000 in five years.

Will, however, is among those who believe youth baseball will recover. He points to a period during the 1950s when major league attendance was at an all-time low.

“It’s not good where baseball is, but it’s not incurable,” Will said. “Baseball has enormous staying power.”

More to Read

Get our high school sports newsletter

Prep Rally is devoted to the SoCal high school sports experience, bringing you scores, stories and a behind-the-scenes look at what makes prep sports so popular.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.