SKELETON CREW

- Share via

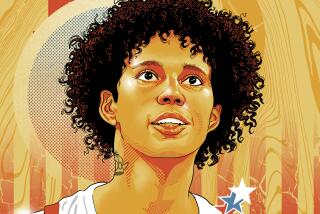

Noelle Pikus-Pace’s journey to Sochi, Russia, began the moment she walked away from skeleton racing after the Vancouver Games.

Seemingly content with her fourth-place finish in 2010, she no longer wanted to spend months on the road, moving from country to country while her family stayed behind. She wanted to be home with them in Utah, where she didn’t have to worry about missing both the extraordinary and mundane moments in her daughter Lacee’s life.

She would, of course, miss the thrill of competing and whipping headfirst down an icy track at 90 mph. But those feelings seemed insignificant when compared with how much she had missed her family while competing on the World Cup circuit during the previous two seasons.

With little regret, the United States’ most successful slider hung up her sled and focused on growing her young family.

After giving birth to her son, Traycen, in March 2011, she toyed with the idea of a comeback but fate soon intervened. By Traycen’s first birthday, she was pregnant again with her third child -- another girl -- and her family once again took precedence over skeleton racing.

“I thought the comeback just wasn’t meant to be,” she said. “I was all right with that.”

Her life, however, took a devastating turn in April 2012, when she suffered a miscarriage at 18 weeks. In the months that followed, Pikus-Pace and her husband, Janson, both devout Mormons, used prayer to help deal with their grief and figure out their future.

Knowing his wife needed to do something that brought her joy, Janson Pace suggested that she start racing again.

“I just needed something to move on with and my husband still knew I loved doing skeleton,” Pikus-Pace said.

She returned to the track in the summer of 2012 and found the solace she had been seeking. Her comeback, however, came with a caveat: The entire family had to join her on the road. No more traveling solo, no more long separations or missed milestones.

“We were going to do this together or we weren’t going to do at all,” Pikus-Pace said.

It seemed, at first, an improbable plan. It would cost more than six figures for the family to travel the World Cup circuit together, money they simply didn’t have. They began fundraising efforts and took their case to social media, where they posted a video of Lacee, then 4, asking people to support her mom’s Sochi bid.

“Even donating $1 helps our family get closer to this dream,” Lacee says, before lowering her voice to a conspiratorial whisper. “She really wants to win a gold medal. Please, please, please help us.”

Family, friends and total strangers responded with enough money to fund Pikus-Pace’s comeback campaign and she repaid their generosity last year with one of her best seasons. With her family trekking with her to nine countries over four months, she finished second at the world championships and became an immediate medal favorite in Sochi.

Traveling with two young children can be daunting under any circumstances. Traveling with two kids under the strain of focusing on Olympic competition can make one long for the peace of flying face-first down an ice chute on a cookie sheet.

Pikus-Pace, 31, acknowledges it isn’t always easy for four people to share a single hotel room, especially on nights before big races. If one of the kids has difficulty sleeping, for example, no one gets any sleep.

Her husband tries to ease her burden as much as possible, but there’s enough work to keep them both busy. On competition mornings, she feeds the kids breakfast, helps get them dressed, double checks the diaper bag and packs her own gear before turning her attention to the track.

“It helps, in a way, because I don’t have time to sit around and worry about the race,” Pikus-Pace said. “There are too many other things to do.”

Her success caught the attention of big-name sponsors such as Kellogg’s, Pampers and Procter & Gamble -- all makers of mom-friendly products -- and it has eased her family’s financial burden in an Olympic year. She has dominated her sport this season, reaching the podium in nine of 10 races. She won the 10th race, too, but was disqualified for a sled violation in a controversial post-race inspection.

Pikus-Pace finished second in the World Cup standings behind Britain’s Lizzy Yarnold this season, creating arguably the most exciting rivalry in sliding sports today. Both women are expected to make the medal stand in Sochi, though they’ll face tough competition from German, Russian and Austrian racers.

“Expectations for the team are pretty high,” U.S. Coach Tuffy Latour said. “We’ve had a motto this year: ‘You don’t have to be perfect to be fast.’ And the other thing that we’ve been really focusing on is one corner at a time and let the results happen for themselves. That’s what we’re going to do at the Olympic Games.”

As part of that fun, Pikus-Pace’s entire family will be in Sochi for her first race Feb. 13. She is staying with her husband and kids at a local hotel during most of the Games, but will return to the athletes’ village during her competition, according to the U.S. Bobsled and Skeleton Federation.

She is one of only three mothers on the U.S. Olympic team this year, along with curlers Allison Pottinger and Erika Brown. There are 19 men on the team with children, a dichotomy that experts say reflects the difficult choices many women face when juggling the demands of an arduous career and a young family.

“For any athlete to reach an elite level of competition, it requires hours and hours of work over many years. That takes a toll on your personal life, in general,” said Mary Jo Kane, director of the Tucker Center for Research on Girls & Women in Sport at the University of Minnesota. “To have that kind of demand on your time and to be a mother, it can be incredibly difficult. Men traditionally have been able to do that more easily because of persistent gender roles.”

Indeed, Pikus-Pace’s life is demanding even during her so-called off-season. On the average day, she gets up at 5:30 a.m. to run sprints up and down her subdivision sidewalk while her family is still sleeping. She comes back inside an hour later and lifts weights in the basement until the kids wake up and come find her.

On many mornings, they sit on the stairs, eating Corn Pops and watching her finish her workout. Traycen usually comes and sits on his mom’s stomach, becoming a 35-pound weight that increases the intensity of her sit-up exercises.

“Then I go upstairs, get some breakfast, get Lacee ready for school, change a poopy diaper, shower, go back to the school to pick Lacee up, make some lunch for the kids, clean the house, change a poopy diaper, do some laundry, get dinner ready, change a poopy diaper, go over some sliding runs, look at some sled equipment, put the kids to bed and then do it all again the next day,” she said.

Pikus-Pace realizes she leads a vastly different life from most U.S. Olympians. But though she may have taken a rarely traveled road to Sochi, she says she can’t imagine not taking her family along for the ride.

“As an athlete, everything we do is very selfish. We have to focus on ourselves. We have to focus on when we need to train, when we need to eat. As a mom, it’s the opposite. I have to worry about my kids,” she says. “It’s just been a change in my perspective on life and it has made me so grateful.”

--

Twitter: @stacystclair

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.