The secret life of book reprints

- Share via

My library is truncated. That’s a strange word, but the best one to describe a collection of books built around a big dividing line, the dividing line of my move west. When I came to Los Angeles, in 1991, I didn’t know how long I would be staying; I packed a few hundred books from my library in New York and left the rest.

I know, I know … a few hundred books. And yet, for a person like me, who marks my place in the world through the filter of the written word, a few hundred barely scratches the surface, is the merest minimum with which I’d want to live.

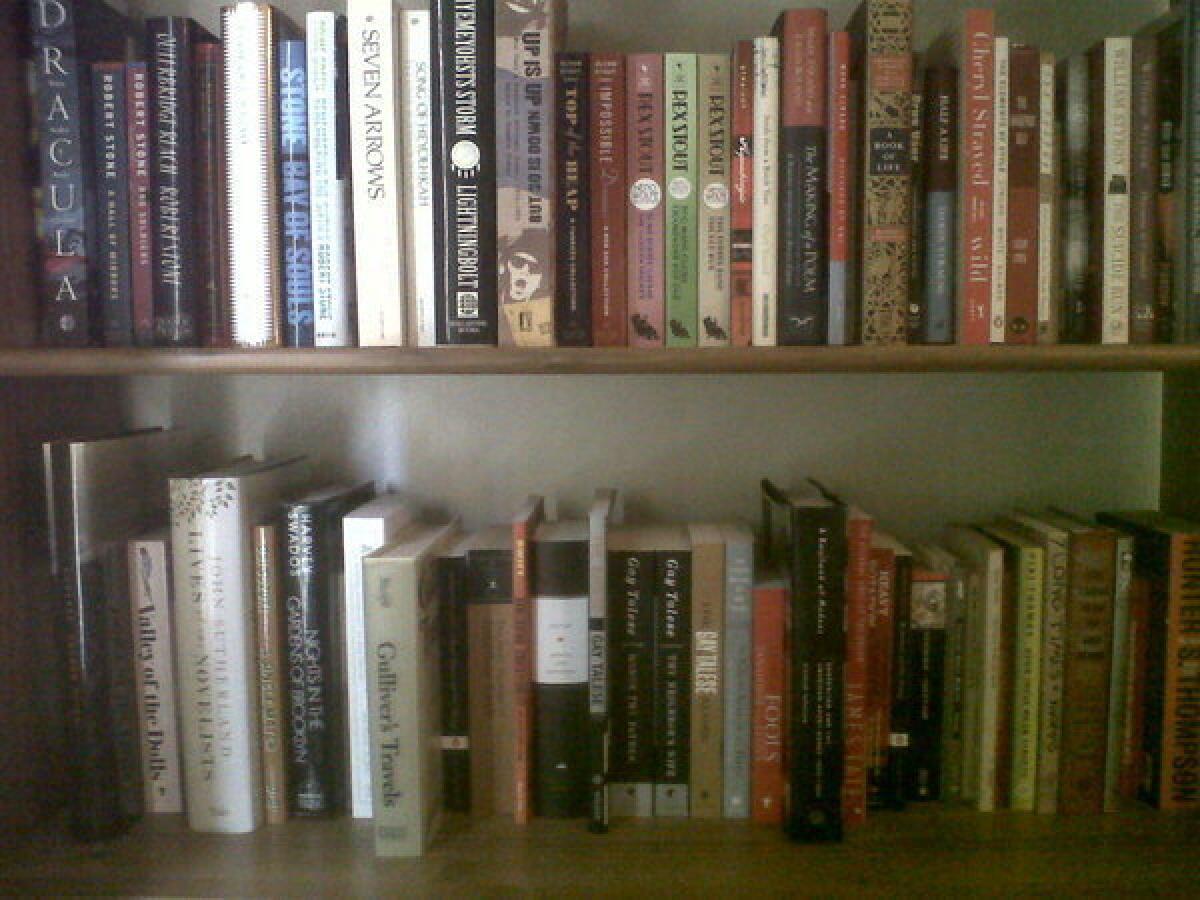

But 1991 was a long time ago, and let’s just say that more books have accumulated since then. Hundreds of them, thousands of them; after building new bookcases last year and embarking on a library-wide reshelving project, we now have close to 4,000 volumes in the house. They stretch, alphabetically by author, from the living room through our bedroom, down the long hall and into the dining room, before finally coming to their end point in my office: more than 100 shelves. Here we see the secret of the book collector — that there is power in numbers, that the gathering of books is both a reader’s and a cataloguer’sart.

And yet, for all its heft, its (yes) weight, there is an air of incompleteness to this library … or maybe it’s just that I see the holes. I’ve always been a completist: If I love your work, I have to own everything. Certain writers — Camus, Faulkner, William Burroughs, Henry Miller, Philip K. Dick — I spent years collecting, buying up dozens of obscure curios, small press monographs, old pulp paperbacks, all of which I put into storage when I left New York.

Not only that, but there are dozens of authors whose early work (the pre-1991 stuff) I have here only if it’s been reissued; otherwise, there is a gap. I look at a shelf of Ss: Although I brought none of his books when I came to California, Robert Stone is represented by a nearly full run, eight of 10, whereas William Styron is spotty, an old paperback of his first novel “Lie Down in Darkness,” and the three volumes of ephemera (“A Tidewater Morning,” “The Suicide Run” and “Havanas in Camelot”) that appeared after his writing life was done. No “Sophie’s Choice,” no “Darkness Visible,” no “The Confessions of Nat Turner” — I’ve read them, and have them still in storage, yet no new editions have come my way.

Why? Partly, it has to do with the way I get books — as a reviewer, in the mail. When I buy a book, it’s never something I already own, so much of my library has been filled out by serendipity, by the title I have but not with me, which have been reissued and sent out.

And yet, this suggests something bigger about reprints, and their role in the intellectual economy. Writing is an art, yes, but it is also a business, and without new publications, an author can disappear.

In the case of Styron — a beautiful writer, deft and heartfelt and disturbing — the work has slipped from view over the last two decades, much as he himself did late in life. Why this is I couldn’t tell you, but both my library and I would be grateful to see some new editions of his books.

ALSO:

Looking back at Charles and Ray Eames

Essential reading after Newtown: ‘Columbine’ by Dave Cullen

Critic’s Notebook: ‘Gatsby,’ ‘Gatz’ and the fallacy of adaptation

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.