California babies aren’t going to the doctor when they should. Here’s why

- Share via

Good morning. It’s Monday, Feb. 26. I’m Jenny Gold, a reporter on The Times’ early childhood education team — and a mom who has done her share of schlepping to the pediatrician’s office. Here’s what you need to know to start your day.

- California is way behind other states when it comes to preventive care for children.

- In Hollywood, homeless encampments fuel neighborhood frustration with L.A. leaders.

- She poured her heart into Arcadia’s Book Rack. Now the small bookstore is closing.

- And here’s today’s e-newspaper.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

California kids aren’t making it to the doctor. Here’s why

Pediatricians recommend that children go to the doctor for regular checkups pretty frequently. For parents, that means taking your baby at least six times in the first 15 months, another two times by age 2 and once every year after that.

But in California, something is amiss. Although 97% of children have insurance coverage, many aren’t actually making it to a doctor. California ranks 46th out of 50 states and the District of Columbia in the percentage of kids ages 0 to 5 who have been to a well-child visit in the last year.

And the problem is worse for the more than half of California children covered by Medi-Cal, the state’s health insurance for low-income residents — including 1.4 million 0- to 5-year-olds.

The California state auditor has issued two scathing reports over the last five years detailing the problem and placing the blame on the Department of Health Care Services. The department said it had made significant improvements to help parents access well-child care. But after digging into the data and speaking with families and advocates across the state, I have found that serious problems remain.

What’s the issue?

Just 42% of children with Medi-Cal got their recommended well visits and screenings in 2021, the most recent year data were available, according to the state auditor. That’s 2.9 million California kids missing out on care each year. For the youngest children, the situation is worse: 60% of 1-year-olds and 73% of 2-year-olds didn’t get their recommended services.

Kids who skip their recommended preventive care can suffer real health consequences: more frequent visits to the hospital, delayed diagnoses of neuro-developmental disorders such as autism, missed cases of lead poisoning, and even greater risk of contracting a vaccine-preventable disease such as measles or whooping cough.

Families report myriad reasons why they can’t take their kids to see a doctor. Some have had to wait months for an appointment. Others haven’t been able to get their Medi-Cal coverage to work or have gotten stuck in a nightmarish loop of bureaucracy. In rural areas, some parents say there’s no doctor near them who accepts Medi-Cal. And many low-income families say they simply can’t get the time off work or obtain transportation.

The state takes the blame

In 2019, the state auditor found the health department had failed to ensure that the majority of children in the Medi-Cal program got the preventive care they were entitled to. They blamed low payment rates to pediatricians and poor oversight of the healthcare plans, and gave the department a list of fixes. In a 2022 follow-up report, auditors said the department still wasn’t doing enough. Access for kids had grown even worse.

Almost all children in Medi-Cal get their care through one of 25 managed care plans that administer the program on behalf of the state. Each plan gets a certain amount of money per member every month to provide care. They can keep what they don’t spend, and they make money by trying to eliminate costly, unnecessary care.

But the monthly rate paid for children is much lower than for seniors or individuals with chronic illnesses, and there’s not much fat to be trimmed on their care. As a result, plans have generally not focused on their youngest members. “Kids are a rounding error,” said Dr. Alice Kuo, a pediatrician and health policy professor at UCLA.

At the end of the day, it’s the Department of Health Care Services that’s responsible for making sure that plans are providing kids with the care they are entitled to under federal law, the auditors determined.

The health department did not agree to an interview, but in an emailed response to my written questions, it said that although a focus on the COVID-19 pandemic had slowed its response, children’s health was a top priority, and it has since implemented almost all of the recommendations and begun to overhaul the Medi-Cal program. The agency said one of its most important actions is to fine plans that fail to provide care to kids.

“To their credit, there is a tremendous amount of transformation going on,” said Alexandra Parma, director of policy research and development at the First 5 Center for Children’s Policy. “But implementation is really, really hard.” Because the changes are relatively new and have not yet trickled down into the available data, it is difficult to know how much access to care is improving.

Earlier this month, the fines became public: Only one of the state’s 25 Medi-Cal plans met all of the minimum standards on children’s health. And 18 fell so far below expectations that they were fined $25,000 to $890,000, including for poor performance on children’s health.

Read more: Hours on hold, limited appointments: Why California babies aren’t going to the doctor.

Today’s top stories

Politics and elections

- In Hollywood, homeless encampments fuel neighborhood frustration with Mayor Karen Bass and Councilmember Nithya Raman.

- If you prefer doing your civic duty the old-fashioned way instead of by vote-by-mail ballot, voting centers have opened across California ahead of the March 5 primary election.

- Research from the small slice of voters who have turned in their ballots so far shows that younger, independent voters are staying on the sidelines.

- California lawmakers can’t take lobbyist donations — unless they’re running for Congress. Eight of them are.

- Gov. Gavin Newsom’s six-figure, multistate ad campaign to fight abortion travel restrictions is set to launch today in several red states.

- California’s top-two primary creates twists and turns in the Senate race.

- Some California D.A.s are fighting fentanyl with murder charges. Why San Francisco will join them.

Science and environment

- Some experts worry California wildlife could be vulnerable to an avian flu “apocalypse.”

- The countdown to NASA’s Jupiter mission is on. This JPL engineer is helping make it happen.

- Scientists warn that a crucial ocean current could collapse, altering global weather.

Crime and courts

- Fake labels, exclusive shoes and hijacked packages: Here’s how the LAPD cracked a ‘sophisticated’ Nike theft ring.

- After two youth brawls last year, a Torrance mall soon will require chaperons for minors.

- Authorities name a mother’s boyfriend as a person of interest in the slaying of 3-year-old boy.

More big stories

- Looking to buy or sell a home this spring? Here’s what to expect.

- The informant next door: A quiet L.A. life masked Kremlin ties for an FBI source accused of lying about Bidens.

- Two friends, each with family trapped in Gaza, are united by anguish. ‘I should be there to protect them.’

Get unlimited access to the Los Angeles Times. Subscribe here.

Commentary and opinions

- Erika D. Smith and Anita Chabria: If California wants to solve homelessness, it’ll have to support reparations.

- Editorial: Shame on FEMA for trying to stiff L.A. for millions spent on a pandemic homeless program.

- LZ Granderson: Your U.S. history class needed a film like “Rustin.”

- Mark Swed: Happy 95th birthday, Frank Gehry. Let’s give you the Disney Hall you really wanted.

- Robin Abcarian: MAGA Republicans pushing to impeach Biden don’t seem to notice the egg on their faces.

- Doyle McManus: Trumponomics? He would impose the equivalent of a huge tax hike.

Today’s great reads

Migrant arrests are up along the border in California and dropping in Texas. Experts told The Times’ Andrea Castillo that a combination of factors was likely causing the shift, including Texas’ anti-immigration policies.

Other great reads

- “When you’re in a bookstore, you have to be a dreamer”: Arcadia’s Book Rack is closing after 40 years.

- This activist investor is behind Disney’s boardroom drama, but he faces long odds.

How can we make this newsletter more useful? Send comments to essentialcalifornia@latimes.com.

For your downtime

Going out

- 💐 Want to romanticize your life? Try these 11 L.A. activities for quality solo time.

- 📽️ Box office doldrums continue, but “Dune: Part Two” is on the horizon.

Staying in

- 📺 Anna Sawai explains why her “Shogun” role felt personal.

- 🧑🍳 Here’s a recipe for Island Turkey-Rice Salad.

- ✏️ Get our free daily crossword puzzle, sudoku, word search and arcade games.

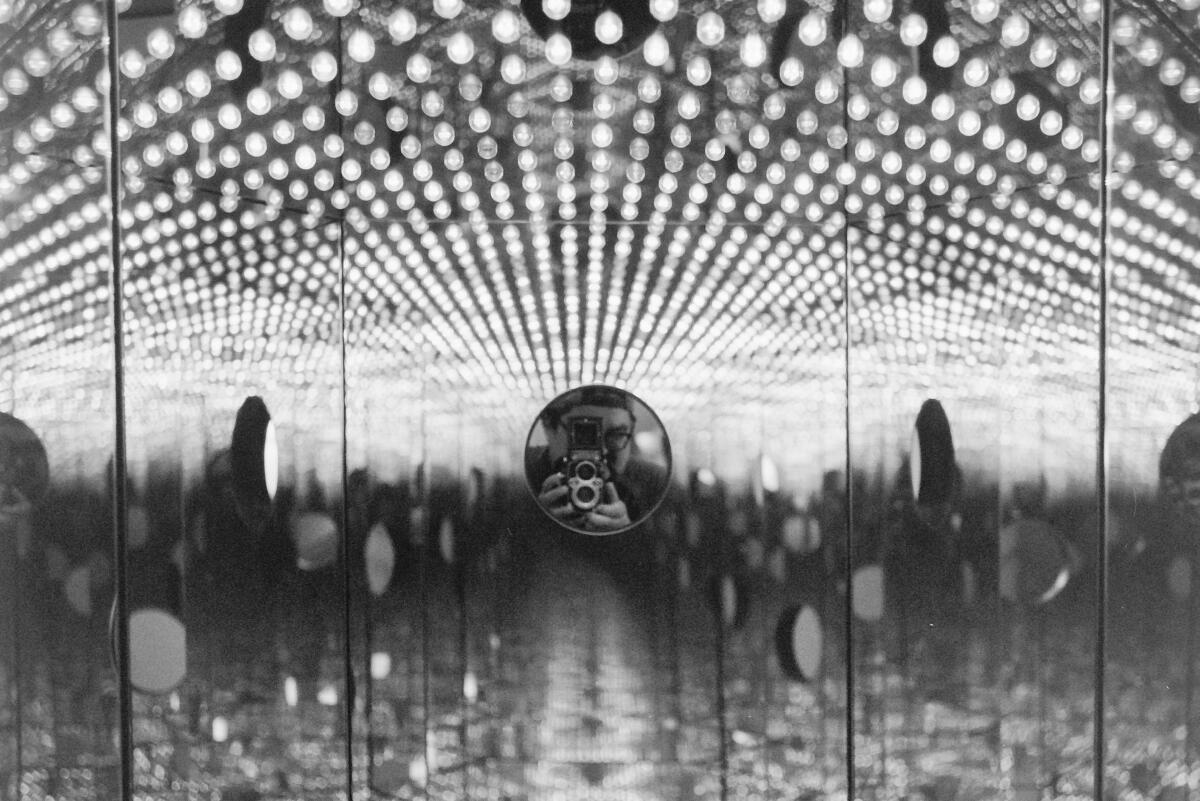

And finally ... a great photo

Show us your favorite place in California! Send us photos you have taken of spots in California that are special — natural or human-made — and tell us why they’re important to you.

Today’s great photo is from former Times reporter Greg Yee, who died in January 2023 at age 33. Michael Chin and Natasha Aftandilians, two of Greg’s college friends, recently pored over hundreds of photos he took in L.A. and published a selection of them on what would have been Greg’s 35th birthday. “Simply put: His photographs are a postcard home, from home,” they wrote.

Have a great day, from the Essential California team

Jenny Gold, reporter

Karim Doumar, head of newsletters

Check our top stories, topics and the latest articles on latimes.com.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.