Sierra fire’s unstoppable path of destruction devastates town, sends residents fleeing

- Share via

As the sun set in the Sierra Nevada Friday, about 50 residents of the mountain hamlet of Big Creek gathered on an overlook at the edge of town. The Creek fire, as it would be called, had just started burning in the canyon below.

It seemed minor, and those assembled looked on hopefully as planes and a helicopter dropped water on it.

“It was a Friday night, something to watch, something to do. We are a bunch of hillbillies,” joked Toby Wait, the superintendent, principal and gym teacher for the town’s 55-student school. “Fire is part of our lives, but this was small.”

It didn’t stay small.

In the hours and days that followed, the Creek fire has exploded into a monster inferno that has consumed nearly 100,000 acres, enlisted nearly 1,000 firefighters, isolated small foothill communities and threatened to burn until mid-October.

Record heat. Raging fires. What are the solutions?

Get Boiling Point, our newsletter about climate change, the environment and building a more sustainable California.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

California’s fire season got an early start this year with the massive lightning fires in the coastal mountains and wine country. Even without the fall Santa Ana winds, more than 2 million acres have burned so far in 2020, more than in any previously recorded year. Now the Creek fire promises to be one of the worst of the season.

For the mountain communities lying east of Fresno, the assessment as of Monday afternoon looked especially grave.

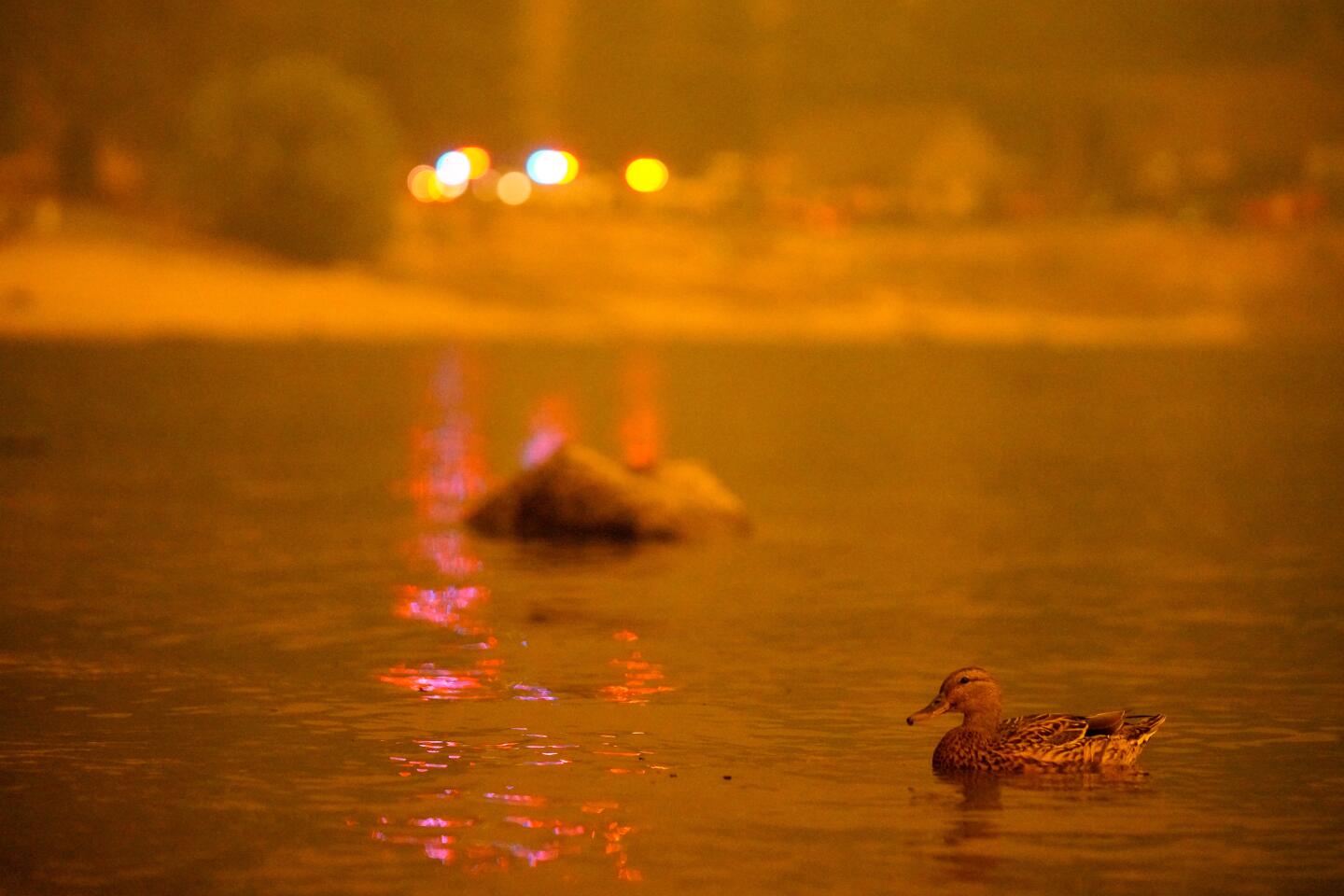

Fueled by millions of dead trees, the Creek fire has raced through mountain communities like Big Creek and vacation getaways like Huntington and Shaver Lake, confounding firefighters with unpredictable and terrifying behavior. Its smoke plumed nearly 50,000 feet high. There were lightning strikes. Forests seemed to explode.

The drama seemed to peak Saturday night when a CH-47 Chinook and UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter rescued some 200 campers trapped by flames at Mammoth Pool.

Intense Diablo winds are forecast for parts of Northern California while Santa Ana winds are expected in Southern California.

But among the thousands fighting the fire or evacuating from its path, there have been no reports of deaths.

Damage to property and homes is more difficult to assess. The fire is burning so dangerously and intensely that crews who normally count destroyed houses and buildings have been told to stand down for their own safety.

::

On Friday night, Christopher Donnelly, chief of the Huntington Lake Volunteer Fire Department, was monitoring the fire, which had been knocked down from three acres to one. He had gone to bed that night confident the fire was under control.

But on Saturday morning, he was up at 5:30 hearing sirens from the Fresno County sheriff’s department streaming by his cabin on the north shore of Huntington Lake. Donnelly, a monk with Christian Brothers who spends his summers at a local church camp, was soon following the vehicles down the steep grade to Big Creek.

The town of some 200 residents was being evacuated. The air drops had had to stop during the night, giving the fire opportunity to continue to chew through dense, dry vegetation and stands of pines killed by pine bark beetles.

Volunteers from the Big Creek Fire Department had taken to the streets with bullhorns, telling everyone to leave. It was a scene that would soon be repeated among communities throughout the region.

At Mammoth Pool recreation area in the Sierra Nevada, a nighttime airlift rescued victims trapped by the Creek fire

School Supt. Wait and his wife, Stephanie, a teacher at the Big Creek school, discussed what to take.

“I told her, ‘Sweetie, whatever we put in the car now, we will have to take it out of the car in 24 hours,’” he said, anticipating a quick return to their home by Sunday morning.

They decided to pack the photographs from the walls. Wait mulled taking a nativity set and a cookie jar, both heirlooms from his grandmothers that had little monetary value but were priceless in sentiment. But in the end, he left them behind, figuring they would probably get broken in a truck crowded with their three dogs.

In the predawn hours, the couple joined a caravan of about 60 vehicles out of Big Creek, down a narrow mountain road known as Beaver Slide. In daylight, even without a fire closing in, the cliff-edge route is “four miles of sheer terror,” he said. Now it was dark, and they had no time to waste.

Two hours later, fire chief Donnelly arrived in Big Creek. It was about 6 a.m., and the town was empty except for fire crews from the volunteer fire department, the Forest Service and Cal Fire. Equipment, hoses and trucks blocked the narrow streets.

“I saw the fire about a mile to the west with a huge column of smoke rising about 10,000 feet,” Donnelly said. “I stayed until the wind shifted and filled the place with smoke.”

The shifting wind was the first clue that the fire was about to overrun the town. At night in the mountains, winds flow into the Central Valley, but during the day, they reverse direction and would bring the fire straight into town and then up the grade to Huntington Lake.

Overhead, Donnelly heard two aircraft, air tankers from San Bernardino, flying 2,000 feet above. Through the smoke, he saw one, a four-engine jet that was about to make a drop of fire retardant on the western perimeter of Huntington Lake.

He recommended to the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection incident commander that the cabin communities along Huntington be evacuated as well.

::

Sitting at an elevation of 4,800 feet, Big Creek is home mostly to employees of Southern California Edison, which owns and manages the hydroelectric facilities in the area. The first powerhouse in the Big Creek electrical system was financed by Henry Huntington and went into operation in 1913.

The power plant is still a source of pride for the small town.

“It was Mayberry,” said Wait, describing the town he has lived in since 2011. He left his job as a high school principal in Fresno to work in Big Creek, where his grandparents had lived. It was a dream.

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

The steep slopes around Big Creek last burned in August 1994, when a squirrel shorted out an electrical conductor at an Edison substation. At the time, the town had 400 residents who were evacuated. Erratic winds drove the fire toward the town and skirted it, burning 5,000 acres lying between Big Creek and Huntington Lake.

Since then, reforestation has helped restore the habitat, but with a juvenile forest, the undergrowth grew thick and combustible, and the ancient trees that were left were ravaged and killed by the pine bark beetle.

“There is a lot of tree mortality in the area, and it is really heavily brushed, so the fire is being fueled by the intensity of the vegetation,” said Cal Fire spokesperson Jaime Williams.

A lengthy drought weakened many trees, making them susceptible to fatal attacks by the insects. The beetles have killed as many as 33 million trees, and in the fire area, up to 90% of the trees are dead, according to officials.

“These trees, being so dry and brittle, tend to explode when they catch on fire, which would tend to cause spotting ahead of it,” U.S. Forest Service spokesman Alex Olow said.

::

By Saturday evening — just as the California Air National Guard was making plans to evacuate the people stranded at the nearby Mammoth Pool reservoir — the situation in Big Creek was getting worse.

During the day, fire crews were attempting to save the town, as wind-driven embers were sprinkling its small circle of streets and cul-de-sacs with spot fires that threatened to join up with one another.

Donnelly stayed in touch with Bryan Troll, chief of the Big Creek Volunteer Fire Department, and its former chief, LaDonna Crane, who had recently retired. The fire was racing up both sides of the river that flows through Big Creek.

According to Crane, all the homes on Point Road — a tree-shaded lane connecting a U.S. Forest Service facility with the center of town — were lost. A landscape of oaks, country homes with fenced yards and streetlamps had become a wasteland of charred trees, solitary brick chimneys and teetering power lines.

California has a long history of lightning-caused fires, but 2020 is showing how a changing climate can affect the growth of such blazes.

In addition, two propane tanks, containing 5,000 gallons of fuel and belonging to Southern California Edison, exploded, as did the tank at the community swimming pool.

To some, it was reminiscent of Paradise, Calif., in the aftermath of the Camp fire. Only no one had died.

Critical personnel had been sheltering in a new administration building belonging to Southern California Edison, and late in the day, efforts were made to maintain a safe perimeter around the parking lot. By then, the plant was no longer generating power.

But by 8 p.m. the area’s incident commander ordered everyone out of Big Creek except for a small strike force. Two hours later, that crew reported a drop in water pressure; Big Creek had run dry.

Crane’s son, Nathan, and a few others who served on the volunteer fire department returned to the burning town and succeeded in reconnecting the town’s water supply with the big conduits running between Big Creek and Huntington Lake.

::

On Monday morning, Wait and Stephanie were staying with family in Hanford, hoping for any news from Big Creek. With power lines lines down and electricity out in the region, they had little to go by.

Some of the small neighborhoods — known by residents as Company Town and Jungle Town — are rumored to have been lost.

Sheltering throughout the state, Wait and his neighbors had been told that as many as half the houses were destroyed. The town’s school had caught fire but seems to have been saved.

U.S. Forest Service spokesman Olow confirmed the town “did receive significant fire damage,” though he said a more precise accounting would have to wait.

“The fire behavior is so extreme ... the damage assessment teams ... can’t gain access, and it is for their safety they stay back,” he said.

Looking at pictures and video of Big Creek from the text messages of friends, Wait struggled not to cry. He said he was slowly coming to terms with the fact that his home was a pile of ashes.

Still, he had no regrets for the life they had made in Big Creek.

“If you would have told me this would have happened to me, I would do it again, “ he said. “I would not give up these 10 years, even though I lost everything. That is the type of town and people I lived with.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.