- Share via

When Mariella Rojas goes into her mother’s bedroom each morning, she doesn’t know whether 81-year-old Rosa Angelica Saldana will recognize her.

“Sometimes she’ll say, ‘Mariella,’ and she’ll caress my hand,” the pre-K teacher says. “Or sometimes she’s just staring at me and looks spaced out.”

Her mother, once vibrant and industrious, lived on her own until her world went out of focus about seven years ago. Mariella panicked when she learned Saldana hadn’t returned from an errand; eventually, she found her in a bank, where “she looked so lost.” Another time, her mother got off a bus at her scheduled stop but couldn’t remember how to get home from there.

Mariella, 48, and her family briefly considered moving Saldana to a nursing facility, but the cost at the time, starting at $5,000 a month, was unaffordable. And Mariella says she couldn’t imagine leaving her mother with strangers and worrying about the quality of her care.

Mariella asked her husband, Julio, if it would be OK for her mother to move in with them.

He said yes. His parents were cared for by family in Argentina after he moved to the United States.

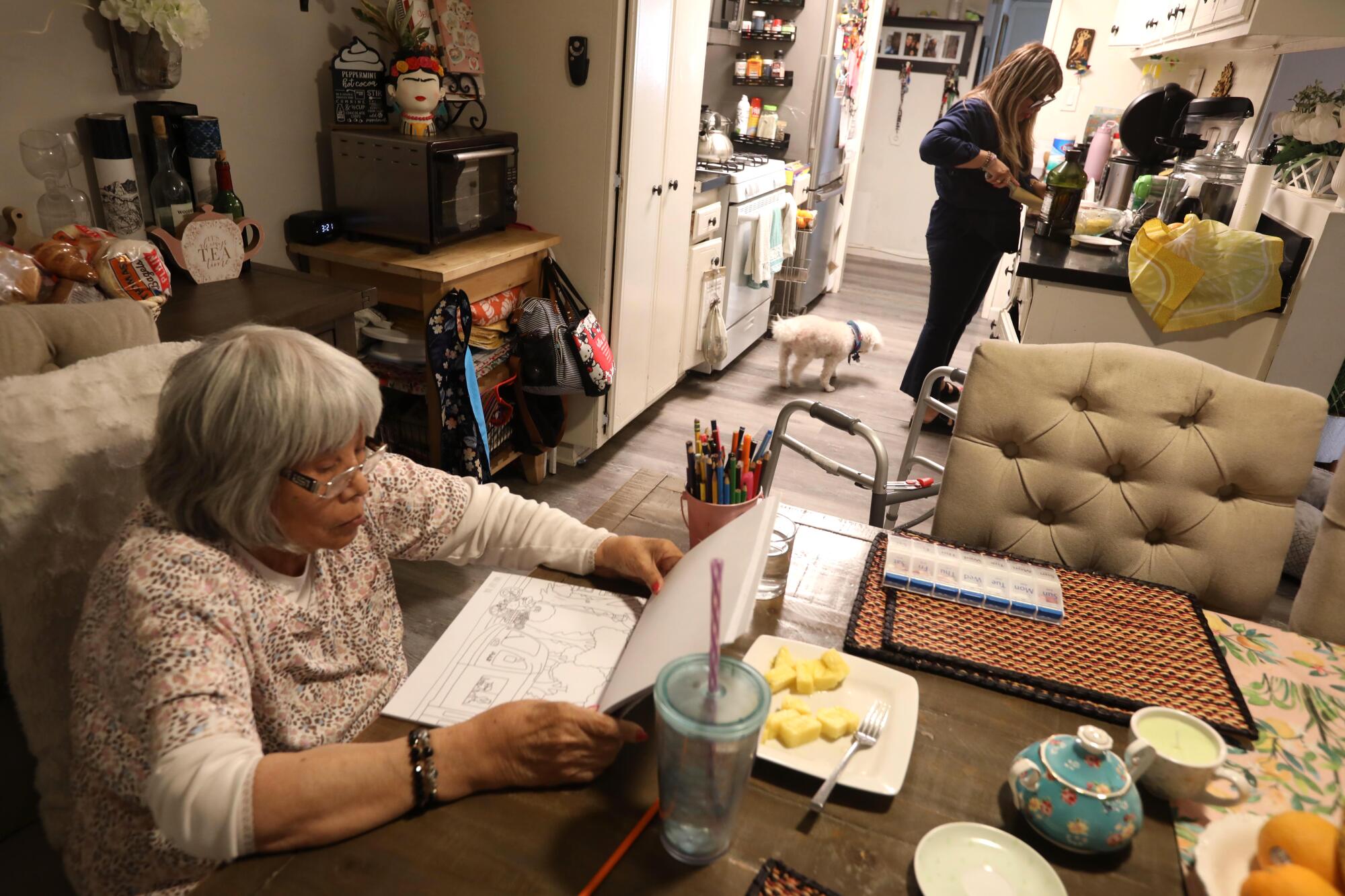

For the last seven years, Saldana, whose cognitive impairment has steadily declined, has lived in a three-bedroom Northridge apartment with Mariella, Julio, their daughter Paola, 19, and son Max, 14. The teens, who used to have their own bedrooms, began sharing one to make room for their grandmother.

California is about to be hit by an aging population wave, and Steve Lopez is riding it. His column focuses on the blessings and burdens of advancing age — and how some folks are challenging the stigma associated with older adults.

“It’s challenging,” Julio, 51, told me after a day of work at a metal casting factory. He was seated at the dining room table across from his mother-in-law, who dug into a spaghetti dinner. “But we needed to help, and we did it.”

As the age wave gathers force in one of the great demographic shifts of our time, a small percentage of people will be able to afford 24/7 in-home care for loved ones, and some will go broke trying. Others will ship family members off to nursing homes or senior villages, but that’s a budget buster too.

Mariella calls her situation an arrangement born of cultural preference — “I’m Latina” — and financial need. But given projected shortages of trained help and the cost of professional care, this model is becoming more common in a nation of unpaid caregivers who are learning on the job, even as they juggle work and other family responsibilities.

“In 2021,” says a report from AARP, “about 38 million family caregivers in the United States provided an estimated 36 billion hours of care to an adult with limitations in daily activities. The estimated economic value of their unpaid contributions was approximately $600 billion.”

To help family caregivers — and they’re certainly going to need help — AARP recommended state and federal tax credits and workplace flexibility, among other things.

Professor Donna Benton, director of the USC Family Caregiver Support Center, said cultural norms, economic hardship and the cost of professional care — particularly in Black, Latino and Asian communities — will make arrangements like that of Mariella Rojas’ family more common.

“I think more people, particularly with the housing crunch, are going to be living together,” Benton said.

1. Mariella Rojas, left, opens her arms after her mother Rosa Angelica Saldana, asked for a hug. 2. Mariella Rojas, left, gives her mother, Rosa Angelica Saldana, a hug. 3. Julio Rojas helps his mother-in-law, Rosa Angelica Saldana, stand up so he can help her get ready for bed. (Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times)

To fully understand Mariella’s devotion to her mother, you have to go back to 1982 in their native Peru. When she was 7, Mariella and her mother were involved in a traffic accident that killed Mariella’s father and 10-year-old sister. Mariella and her mother, badly injured, were hospitalized for a month.

“I don’t remember the car accident, but I remember waking up in the hospital with my mom in the bed next to me,” said Mariella, who also recalls the moment a doctor told her mother that her husband and daughter were gone. “Since that day, I’ve always been next to my mom.”

Five years after the accident, the family moved to Los Angeles in search of a fresh start, helped out initially by friends who also had relocated from Peru. Mariella missed home, but along with her two older brothers, she began to adapt while their mother worked as a nanny, among other jobs.

Mariella recalls her mother’s struggles and insistence — having tragically lost her own provider — that Mariella establish her independence.

“You need to go to school and you need to get a career,” her mother told her, and Mariella recalls her mother’s pride when she became a teacher.

In the morning, when Mariella and Julio get ready for work while Paola and Max get ready for school, an aide from the state-sponsored In-Home Supportive Services program helps Saldana get bathed, dressed and ready for her day.

Mariella’s brother then picks up his mother and takes her to ONEgeneration Adult Daycare in Van Nuys, where she has a full day of games, puzzles, music, group activities, exercise and nursing care. Twice daily, the adults mingle with kids in the adjacent ONEgeneration preschool, reading to them, working on puzzles and sometimes rocking them to sleep.

Most of the adults in the program, including Saldana, qualify for Medi-Cal coverage. And almost all of them, at the end of the day, return to multigenerational homes.

1. After teaching for the day, Mariella Rojas picks up her mother, Rosa Angelica Saldana, from OneGeneration Adult Day Care in Van Nuys. 2. Saldana, gets assistance from her daughter, Marielle Rojas, getting into the family car. (Genaro Molina/Los Angeles Times)

Mariella calls ONEgeneration a lifesaver. The adult day care director there, Michelle Quiroga-Diaz, told me that when Saldana seems out of sorts, the staff has learned there’s a quick remedy. “We often feel like she needs to hear Mariella’s voice, so we’ll call her, and she makes a difference in those moments,” Quiroga-Diaz said.

Mariella arrived at ONEgeneration just after 4 one afternoon to pick up her mother. She greeted her mom in Spanish, and then helped her on a slow walk to the car. Saldana had a knee replacement several years ago and uses a walker, which makes these daily rituals physically and emotionally time-consuming.

After a 15-minute drive home, the Rojas family care system kicks into action. Mariella calls ahead, and Max comes to the gate of the apartment complex while his mother double-parks and hands off Saldana. Max gives his grandmother a hug and walks her back to the apartment while Mariella parks.

Paola, a Pierce College student interested in a film career, used to be on morning wake-up duty with her grandmother but now helps out in other ways. She said that when she had to give up her own bedroom to make room for her grandmother, she was fine with it.

“From the time I was a baby, I was cared for by my grandma while my mother and father were at work,” said Paola. She and Max recall strolling the neighborhood with their grandmother, especially the trips to get ice cream.

Mariella said the family had agreed they’d consider a nursing home when her mother’s needs became too great. It was Paola, though, who resisted when a daily hygiene issue put new demands on the family.

“I said, ‘Paola, we should look into a place,’” Mariella told me. “And she said, ‘I don’t think you’re ready, Mom. And you know what? Don’t worry. I’ll help you.’ For me, those words were so powerful.”

One key to making it work, said Julio, is to leave a part of every Saturday for the four of them to do something together. A helper will come in to watch Saldana, and the rest of the family will go to Little Tokyo, or maybe to the beach, and then out to dinner.

The family has learned, with guidance from ONEgeneration, how to understand and accommodate Saldana’s infirmity — how to resist pushing back when she’s combative or confused.

“You join their world,” Mariella said, offering an example. In the middle of a meal, her mother might call out to Julio, thinking he’s a waiter. Julio will hurry over and ask how he can be of assistance.

Max, who attends Granada Hills Charter and dreams of going to MIT and becoming an engineer, misses the grandma who used to help him with his homework, but he’s found ways to love this evolving version of her. “Most of the time she doesn’t remember who I am,” Max said, seated on the living room sofa while his grandmother watched the news on television. But regardless, he senses that he’s a familiar presence in her mind, and he knows a hug or kiss can draw a smile out of her.

“I don’t know what she wants,” Max said. “But to me it seems like she’s happy, and I want her to be around the people she truly wants to be around.”

A year and a half ago, Mariella’s oldest brother died after a long battle with cancer. She has struggled with whether to tell her mother, but hasn’t, so far. She fears that on some level, despite memory loss, her mother will suffer again, as she did for so many years after losing a husband and a daughter.

A little after 7 p.m., Julio asked his mother-in-law if she was ready to brush her teeth and take her medication. He helped her off an easy chair and into her walker. Sometimes, Mariella said, her mother will take the toothbrush and use it to scrub the bathroom sink, but “you learn to go with the flow.”

Those concessions are not easy to process, nor is it easy to witness the relentless march of such an indiscriminately cruel impairment. But this is the woman who was always there for her, and Mariella now offers the same gift:

“I feel the way to honor my mom is to keep her with me as long as I can,” said Mariella.

Yes, it’s a lot. Yes, it’s hard.

“But you know who taught me how to be strong?” Mariella said as her mother prepared for bed. “That lady.”

Julio tucked his mother-in-law into bed and pulled up the side rails to keep her from falling out. Hanging on the wall is a photo of Mariella, Julio, Paola and Max.

Her mother can be confused when she wakes up, Mariella said, and maybe that photo reminds her she’s in her own home with people who love her.

steve.lopez@latimes.com

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.