Anal Fistulas: What They Are and How They’re Treated

- Share via

Key Facts

- Anal fistulas affect about 2 in 10,000 people yearly, with a higher prevalence in young men.

- Most fistulas form due to blocked anal glands, resulting in infection and abscess formation.

- Fistulas are classified as simple or complex based on their relationship to anal sphincter muscles.

- MRI and endorectal ultrasound are key tools for mapping fistula anatomy before surgery.

- New treatments like stem cell therapy and biologics are advancing care for complex cases.

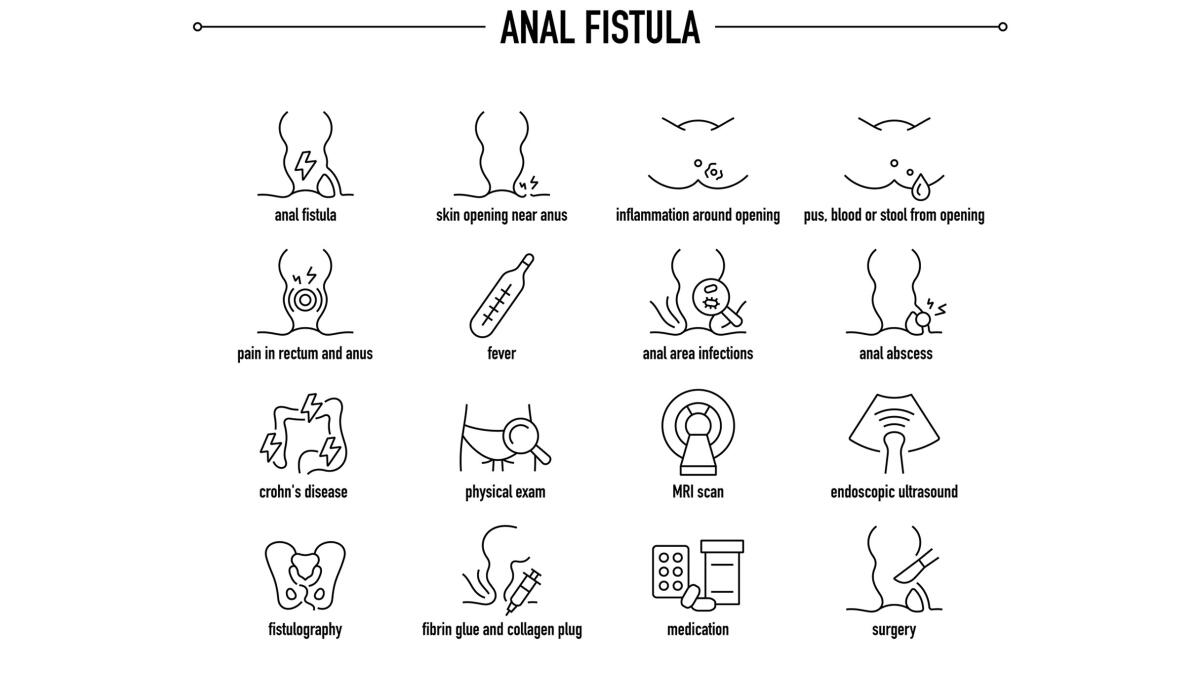

Anal fistulas are more than just a minor annoyance—they’re persistent, painful and often require surgical care. These abnormal channels form between the anal canal and the skin around the anus, usually due to an underlying infection. Anal fistulas most often result from a bacterial infection that starts in the anal glands.

They may seem straightforward on the surface but anal fistulas can be tricky to diagnose and treat. An anal fistula is diagnosed through a combination of symptom assessment and clinical evaluation. Understanding how they develop, how they’re classified and the evolving treatment landscape is key for patients and clinicians.

Table of Contents

- What is an Anal Fistula?

- How Anal Fistulas Form

- Types and Diagnosis

- Treatment Options

- Alternative Treatments

- Closing Thoughts

- References

What is an Anal Fistula?

An anal fistula is an abnormal tunnel that connects the inside of the anal canal to the skin around the anus. These tracts are usually the result of infections in small anal glands; an infected gland can lead to abscess formation and subsequent fistula development.

A perianal abscess, which occurs in the tissue around the anus, is a common precursor to an anal fistula. If these abscesses rupture or are drained they can create a fistula and untreated or recurrent abscesses can become a chronic condition increasing the risk of fistula formation.

Additional risk factors for developing anal fistulas include Crohn’s disease and prior radiation therapy for cancer. According to research 2 in every 10,000 people develop an anal fistula annually with young men being disproportionately affected [11].

In infants, especially males, anal fistulas usually originate from developmental abnormalities involving the anal crypts, or small pockets near the anus [3].

How Anal Fistulas Form

Most anal fistulas are cryptoglandular, meaning they originate from infected anal glands located between the internal and external anal sphincter muscles [4]. When one of these glands becomes blocked bacteria can multiply and cause an abscess. If the abscess doesn’t heal properly—or if it drains through the skin—it may leave behind a permanent tract: the fistula.

This is often sustained by ongoing inflammation or infection and in some cases by underlying conditions like Crohn’s disease, tuberculosis or radiation injury. Because the tract develops in response to inflammation treating just the symptoms (like draining an abscess) without addressing the root cause can lead to recurrence.

Types and Diagnosis

Not all anal fistulas are created equal. They vary significantly depending on their position relative to the anal sphincter muscles and this classification plays a big role in treatment decisions. The fistula tract may pass through or around the internal sphincter and external sphincter muscles which affects the complexity of the case and the choice of treatment.

- Simple vs. Complex: A simple fistula doesn’t cross much of the sphincter muscle making it easier to treat. A complex one may involve multiple tracts or cross a significant portion of muscle and increase the risk of complications like incontinence.

- High vs. Low: This refers to how deep the fistula goes and how much of the sphincter muscle it crosses. High fistulas are trickier to treat safely.

To map out the anatomy of a fistula MRI scans or endorectal ultrasounds are usually used [5]. These tools help surgeons visualize the full path of the fistula, any branching tracts, involvement of the internal sphincter and external sphincter muscles and the location of the fistula’s internal opening before choosing a surgical strategy.

Treatment Options

There’s no one-size-fits-all solution when it comes to treating anal fistulas. The main goals are to remove the fistula tract, prevent recurrence and preserve the anal sphincter muscles to avoid incontinence [1].

However, complications can arise such as recurrence of the condition, severe infections that may require hospitalization and the need for additional procedures or multiple surgeries to address persistent or complex cases.

For simple fistulas:

- Fistulotomy is often the preferred method. This involves surgically opening the fistula tract so it can heal from the inside out [2].

For complex or high fistulas:

- Sphincter-sparing procedures like the loose seton technique are common. A soft thread is placed through the fistula to keep it open and allow for drainage while promoting gradual healing [7], [10].

Other modern options include advancement flaps, LIFT (ligation of intersphincteric fistula tract) and biologic plugs—though their effectiveness can vary based on patient anatomy and the underlying cause.

Challenges in Management

Even with treatment recurrence is a big problem. Up to 30% of patients will experience symptoms again or need further procedures. Surgeries that involve too much of the anal sphincter can lead to incontinence and affect quality of life.

Alternative Treatments

In recent years researchers and surgeons have been exploring minimally invasive and biologically targeted therapies [9]. These include:

- Stem cell therapy for Crohn’s related fistulas

- Laser ablation of the fistula tract

- Fibrin glue and biologic meshes to close the tract while preserving muscle [6]

New techniques aim to reduce the trauma of surgery and increase healing and reduce recurrence.

For example one of the promising areas is biologics to manage the underlying inflammation especially in patients with autoimmune conditions. These are still being evaluated but represent a move towards precision medicine in colorectal surgery.

Closing Thoughts

Anal fistulas are a complex but common problem that goes beyond surface level discomfort. Rooted in infection and inflammation their treatment is all about a fine balance: getting rid of the fistula without compromising the muscle control of continence.

As diagnostic tools and treatments evolve so does the hope for better healing and less recurrence. For patients early evaluation and a tailored surgical plan is key to a good outcome.

References

[1] Charalampopoulos, A., Papakonstantinou, D., Bagias, G., Nastos, K., Perdikaris, M., & Papagrigoriadis, S. (2023). Surgery of Simple and Complex Anal Fistulae in Adults: A Review of the Literature for Optimal Surgical Outcomes. Cureus, 15(3), e35888. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.35888

[2] Limura, E., & Giordano, P. (2015). Modern management of anal fistula. World journal of gastroenterology, 21(1), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.3748/wjg.v21.i1.12

[3] Poenaru, D., & Yazbeck, S. (1993). Anal fistula in infants: etiology, features, management. Journal of pediatric surgery, 28(9), 1194–1195. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3468(93)90163-f

[4] Sohrabi, M., Bahrami, S., Mosalli, M., Khaleghian, M., & Obaidinia, M. (2024). Perianal Fistula; from Etiology to Treatment - A Review. Middle East journal of digestive diseases, 16(2), 76–85. https://doi.org/10.34172/mejdd.2024.373

[5] Bubbers, E. J., & Cologne, K. G. (2016). Management of Complex Anal Fistulas. Clinics in colon and rectal surgery, 29(1), 43–49. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0035-1570392

[6] Malik, A. I., & Nelson, R. L. (2008). Surgical management of anal fistulae: a systematic review. Colorectal disease : the official journal of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland, 10(5), 420–430. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2008.01483.x

[7] Litta, F., Parello, A., Ferri, L., Torrecilla, N. O., Marra, A. A., Orefice, R., De Simone, V., Campennì, P., Goglia, M., & Ratto, C. (2021). Simple fistula-in-ano: is it all simple? A systematic review. Techniques in coloproctology, 25(4), 385–399. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10151-020-02385-5

[8] Sneider, E. B., & Maykel, J. A. (2013). Anal abscess and fistula. Gastroenterology clinics of North America, 42(4), 773–784. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gtc.2013.08.003

[9] Ji, L., Zhang, Y., Xu, L., Wei, J., Weng, L., & Jiang, J. (2021). Advances in the Treatment of Anal Fistula: A Mini-Review of Recent Five-Year Clinical Studies. Frontiers in surgery, 7, 586891. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsurg.2020.586891

[10] Eitan, A., Koliada, M., & Bickel, A. (2009). The use of the loose seton technique as a definitive treatment for recurrent and persistent high trans-sphincteric anal fistulas: a long-term outcome. Journal of gastrointestinal surgery : official journal of the Society for Surgery of the Alimentary Tract, 13(6), 1116–1119. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11605-009-0826-6

[11] Ommer, A., Herold, A., Berg, E., Fürst, A., Sailer, M., Schiedeck, T., & German Society for General and Visceral Surgery (2011). Cryptoglandular anal fistulas. Deutsches Arzteblatt international, 108(42), 707–713. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2011.0707