In wake of Juice Wrld’s death, the tragic tale of SoundCloud rap star Lil Peep looms ever larger

- Share via

In October of 2017, the rapper Lil Peep returned home from tour much as any 21-year-old would come home from college on a break.

“He was complaining that his bottom lip was cracked and split because of way he held the mike,” Peep’s mother, Liza Womack, said. Womack is a first-grade teacher who lives in suburban Long Island, N.Y. She was incredibly close to her son, born Gustav Ahr, and loved looking after him in the days between tour dates. “So I showed up on Halloween with two tubes of Aquaphor to make sure he was OK. Typical mom stuff. He’d call me when he needed me.”

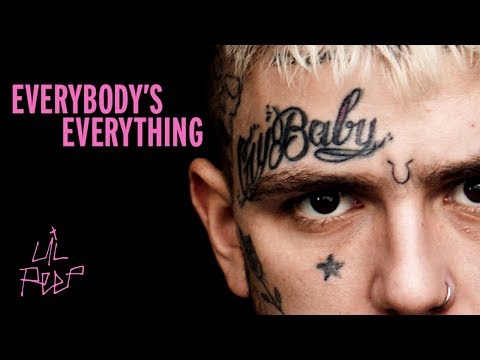

Just days later, Peep would be found dead, from an overdose of Xanax and fentanyl, leaving behind a devastated extended family and a body of profoundly influential music. Two years on, “Everybody’s Everything,” a new documentary and soundtrack album, add layers to Peep’s legacy.

That legacy takes on even greater weight this week when coupled with the sudden death of his peer, 21-year-old rap star Juice Wrld, following a seizure that may have been brought on by a drug overdose, according to law enforcement sources. These deaths, along with the 2018 murder of Peep collaborator XXXTentacion, have led to a call for the music industry to take better care of its young, often troubled artists.

At November’s Camp Flog Gnaw, Juice Wrld paid tribute to fallen rappers XXXTentacion, Nipsey Hussle, Lil Peep and Mac Miller. On Sunday, he died at age 21.

Juice Wrld even had a song about Lil Peep and XXXTentacion, “Legends,” that presaged him prematurely joining his friends: “What’s the 27 club? / We ain’t making it past 21.”

“Kids are looking for leadership in our society and we’re giving them none because we can make a fast buck off them,” said Bob Forrest, an L.A.-area addiction counselor who served on the board of MusiCares, and who grew up performing in the L.A. rock scene alongside such drug-heavy acts as the Red Hot Chili Peppers and Jane’s Addiction. “On YouTube and SoundCloud, there are hundreds of kids who think they’re going to be Peep or Juice Wrld. These kids don’t know there’s a next stage of life. I loved Peep’s music, but someone needed to get a hold of that kid because he was dying in public.”

Liza Womack wants to prevent other parents and nascent artists from facing the same fate. She has filed a lawsuit against Peep’s management alleging negligence and wrongful death. The suit could influence how the industry treats its young talent in the future.

“I certainly never anticipated being in position,” Womack said of assembling the last pieces of her son’s career. “But on the other hand, it’s a way of not letting go of being his mom.”

Lil Peep emerged from the wilds of the late 2010s SoundCloud rap scene, and helped invent a genre halfway between heavy trap music and tender, introspective rock. Peep became a distinct voice from a rising Gen Z, reflecting and shaping their ideas about love, depression and ambition.

With model-striking good looks and an uncommon candor about his own struggles with drugs and mental health on songs including “Awful Things” and “Better Off (Dying),” fans identified not just with his vision but with Peep as a person. That’s part of what made his death so troubling not just to his family, but the music industry at large.

Peep’s death before a Tucson concert in 2017 was harrowingly foreshadowed by an Instagram video posted hours before, which showed him looking glazed and dissociated on a tour bus pouring yellow pills into his mouth. The SoundCloud rap scene was notorious for its drug use, often abusing prescription pills such as Xanax that became a go-to metaphor in lyrics.

“If you have artists foreshadowing that they’re not going to live through their 20s, that makes it more normative,” said Adam Leventhal, the director for the USC Institute for Addiction Science and the Health, Emotion & Addiction Laboratory. “It’s interesting to see that mentioned in modern music, because it’s an additional signal that we have an epidemic. Art is a reflection of reality.”

Over the last year or so, Womack — the executor of her son’s estate — spent months going through his hard drives and voice memos, piecing together the mix notes and song structures the 21-year-old left to guide what became “Everybody’s Everything.”

“There were days when I’d scream-cry,” Womack said of life after her son’s death. Compiling and finishing the record and documentary “makes me miss him every day. But I’ll be damned if I’m not going to do my best by him.”

The album and documentary take their title from an Instagram post around the time of his last performance, in El Paso the day before: “I just wanna be everybody’s everything I want too much from people but then I don’t want anything from them at the same time u feel me I don’t let people help me but I need help but not when I have my pills but that’s temporary one day maybe I won’t die young and I’ll be happy?”

His persona was based around a certain image of youthful nihilism and heartsick romance shellacked with pills and drugs, but the line between Peep and Gus was always liminal. For artists such as Peep and Juice WRLD who rocket to fame based on a self-abnegating persona, it can be hard to separate the two.

“I think he was very aware of the Peep thing being separate — it was an alter ego,” said Sebastian Jones, who co-directed the “Everybody’s Everything” documentary with Ramez Silyan. “But the longer you stay in that, the lines get blurred. Does Gus control Peep, or does Peep control Gus?”

The doc, executive produced by famed director Terrence Malick, digs underneath Peep’s public image to show him reconciling his ambitions and sweet-tempered personality with his private demons and addictions, all under the gloss of new fame. Malick is a friend of Peep’s family, and the documentary was, in part, a way to help those who knew him make some sense of the loss. “His death really rattled cages and it was an open wound for people. A lot of people didn’t have answers,” Jones said.

Womack is also an executive producer of the film, and Peep’s grandfather gives loving voice-over narration.

The accompanying soundtrack album of “Everybody’s Everything” is a look at what might have come next. This posthumous release (some of it previously put out on mixtapes and EPs) was a last chance to show Peep’s arc as a writer, moving toward a more hopeful, layered and melodically ambitious direction.

“He was always a voice for lost youth, but I saw him venturing into a more positive note,” said Alex Tumay, the engineer and mixer who worked on much of “Everybody’s Everything.” Tumay has mixed for Drake, Kanye West and Travis Scott, but his job on this record — filling in the gaps and intentions left by an absent artist, with Womack’s guidance — was a responsibility unlike any in his career.

“I had to take a break after that record, to take a few days of deep breaths to recenter,” Tumay said.

Womack saw the distressing scene around her son in his last months. She knew he struggled with drugs and was torn up about how to intervene.

“I’d call and text him; his grandma and grandfather and brother would call and text,” she says. “We were all worried about it. We knew he didn’t want to go on that last tour. He was exhausted, and it really took its toll on him.”

Those worries are why, in October, Womack sued Peep’s management firm First Access Entertainment and his day-to-day tour managers for negligence, wrongful death and breach of contract, claiming they helped supply him with drugs and failed to look after his health and stability on tour.

Womack declined to discuss the suit, filed in Los Angeles County. In a statement first given to the New York Times, First Access said, “Unfortunately, in spite of our best efforts, [Ahr] was an adult who made his own decisions and opted to follow a different, more destructive path. While First Access is deeply saddened by Lil Peep’s untimely death, we will not hesitate to defend ourselves against this groundless and offensive lawsuit.” First Access did not directly respond to messages requesting comment.

“I see this every day, a kid becomes an overnight sensation, makes millions, and they’re a train wreck,” Forrest said. “My job now is not even educating these kids about drugs, it’s to inspire them that life is worth living.”

Music scenes such as SoundCloud rap vividly document this despair but shouldn’t be blamed for creating it. “This is a reflection of reality, it’s not one culture or group or region,” Leventhal said.

Some industry figures including Tumay agree. “I honestly believe record deals should be forced to have a therapist attached,” Tumay said. “Have some person assigned to an artist to check on their mental health. [Labels should] say, ‘We’re not signing you unless you go to therapy.’ ”

What happened to Peep, one of the scene’s most sympathetic narrators and gentle personalities, and Juice WRLD, another act torn between addiction and hopes for better days, shows the desperate need for change in how the industry looks after its young artists. But any silver linings and celebration of Peep’s work will be just that — last works from an artist with so much left to do.

“The person I was died when Gus died,” says Womack. “There’s a broken part that you just never get over. But I’m still his mom and I still have to look out for him.“

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.