‘Shameless’ boss says peak TV must end: ‘Everybody can’t continue to lose billions’

- Share via

John Wells is the kind of TV viewer most showrunners dread. The veteran writer and producer, now showrunner of Showtime’s “Shameless,” is as overwhelmed as the rest of us by the impossible ratio of TV shows-I-should-watch to available hours.

“I’ll give up on things very quickly now,” he says inside his office in Los Angeles. “If it doesn’t get me fast, then I’m out, because there’s too much other stuff that I know I should be watching.”

Wells wastes little time listing some of the shows from the last year that did hold his attention: “There was no moment in ‘Fleabag’ that wasn’t beautifully done. I hate to say I loved ‘Chernobyl,’ because it was very difficult watching, but I thought it was brilliantly done, and I just got completely immersed in that world. It took me a while to put it on because I was worried about it, just emotionally. I felt the same way about ‘Unbelievable,’ which I think is nigh-on perfect.”

Wells is all too familiar with the pressure to engage viewers. Throughout his storied career, the former WGA president has been part of some of television’s most acclaimed and popular series, including “China Beach,” “ER” and “The West Wing.” His production company, John Wells Productions, recently renewed its overall deal with Warner Bros. Television through 2024, extending the producer’s relationship with the studio to nearly 40 years.

“Shameless,” which currently occupies his time, returns Sunday for its 10th season. The series, about a family living in Chicago’s South Side and struggling with poverty and an alcoholic father, is the longest-running original scripted series in Showtime’s history and remains one of the network’s strongest ratings performers.

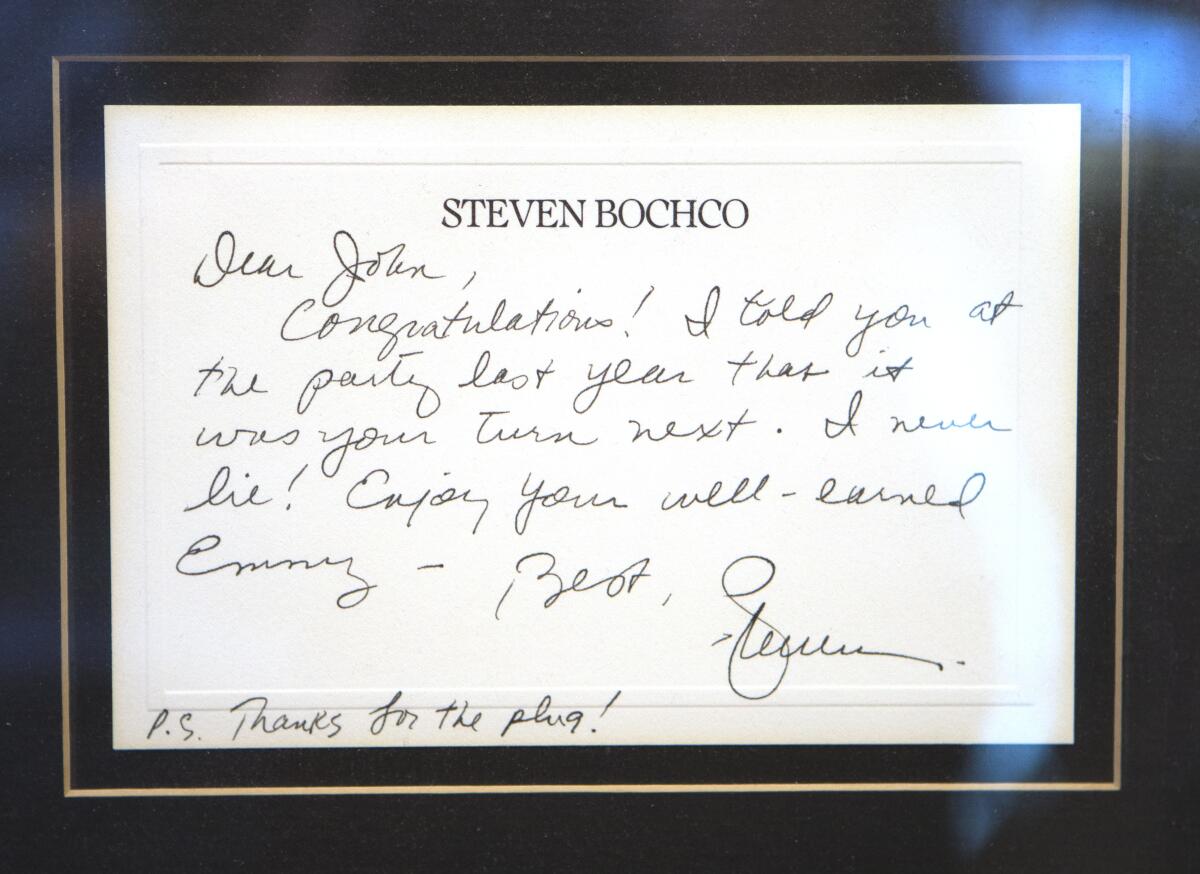

Ahead of the dark dramedy’s season premiere, Wells talked about the advice he got from veteran TV producer Steven Bochco, his concerns about peak TV and keeping “Shameless” relevant.

‘People didn’t think this kind of family existed in the United States’

It took seven years before we got this show made. And it was sort of remarkable to me, given some of my history and various family experiences, [but] people didn’t think this kind of family existed in the United States. When I first started pitching, people didn’t understand what the income inequality was and how unbelievably difficult it is to work your way out of more impoverished circumstances. This American dream, this idea that we have this meritocracy, is an extraordinary, wonderful ideal, but we can’t believe that it’s true and that it actually functions that way.

There are millions and millions of people living in these circumstances where you’re barely scraping by the smallest thing. I’ve forgotten what the exact statistic was, but it was like 40% of the country doesn’t have $400 to deal with if anything happens — and that was a recent statistic.

Once we started telling the stories, what I started hearing with people who were watching the show was, “Frank reminds me of my dad.” They don’t mean that he literally reminds them of their dad. They mean things in these characters: the way that family pulls together to make it through; the way they love each other with all of their faults; and all the ways that they just barely are scraping by. We want to spend time with them, because they’re figuring out how to get through the hard times that far more than half the population of this country has to go through. Now, in this polarized environment in which we exist, it’s even more important that we look at the way that a lot of people have to live.

‘People had their faces tattooed on their arms’

I’ve had a lot of shows with a lot of actors who’ve left to pursue other things, which they have every right to do. And I understand them when they do. As writers, it provides all different kinds of opportunities to tell new stories. And in Emmy Rossum’s case, with [her character] Fiona gone this season, we’re getting into what happens when the big sister who’s held everything together goes. And everybody has grown up, basically. Debbie [Emma Kenney] feels like she should step into that role, but her older brothers are like, “I’m sorry. What do you want to do, little girl?” And I think that is the dynamic that we all struggle with. Our families do often change — family members suffer illness, death; they move away, get married, whatever it is. And there’s this idea of: How do we reorganize ourselves to survive? So it’s very good story material. And we’ll know where Fiona ended up very early into the season.

With Ian and Mickey [a couple, played by Cameron Monaghan and Noel Fisher, that became popular with fans], the reaction was intense. People showed up on our set somewhere who actually had their faces tattooed on their arms. I’m like, “Whoa, they’re into this.” As often happens, people go off and they do some other things and they come back and say, “That was fun. Let’s come do some more.” We were in a readthrough [of an episode] yesterday with a whole storyline that’s going on with them, and we were just laughing. It’s a work family. People leave to go do other things. They want to pursue other challenges. If you keep that environment where you’re not like punishing people because they have other ambitions, then you can have a relationship in which people come back when it’s right.

I don’t know if it’s possible to do what we did when we brought George Clooney back on “ER.” George is a good friend and I called him up and said, “So you don’t want this to come back as a big event ‘cause you don’t want to pull focus off of the show.” We shot this footage, we kind of swore everyone to secrecy. Warner Bros. gave us a plane, we flew up to somewhere in the Pacific Northwest. Shot it on one day and then all went our separate ways. I had the film in my refrigerator for a while and then we’d processed it. We sent them the episode without that scene, and I processed it like on a Monday. We put it in on Tuesday and the network didn’t know about it. So they were a little mad because they could have promoted it, but we didn’t want to promote it. We wanted it to be something special for the audience. Then [NBC] did throw together a really quick promo that they ran before the West Coast airing. I don’t know if that would be possible with social media now.

‘This falls apart like a cheap suit’

I was very afraid to show people my stuff for a long time when I was just starting out. I just didn’t think it was good enough. And so that ended up being very helpful, because I actually did like four years where I really wasn’t trying to get work off the things I was writing. During that period, that was when “Hill Street Blues” was on, and I had given my material to [fellow Carnegie Mellon alum] Steven Bochco, which he didn’t have time to read. But then he got fired off of the show, and he had time to catch up on this huge pile of pathetic begging letters and scripts from me.

I came into his office at 20th [Century Fox] — he had a lot going on, so I waited for a while. He had my script and he kind of threw it across the coffee table at me and said, “This falls apart like a cheap suit, but I think you may be a writer” ... which was more than I had hoped for. And then [he] proceeded to tear the script completely apart. And then he said: “Just keep writing.” The other thing he said, which is a story I tell when I talk to other writers, is he asked me, “If you stacked all your work up on the floor, would it be six inches high, a foot high or two feet high? And I said, “Probably like eight inches.” And he said, “Well, when it’s about 16 inches high when you stack it on the floor, you’re probably going to start to know what you’re doing.” And I think that’s true. It’s a craft and people can be very, very talented, but there’s a repetition to getting better at it.

‘A horrible game of musical chairs is going to start’

I expressed in the [recent Writers Guild of America West] election that I felt we should be back at the negotiating table [in the guild’s ongoing dispute with Hollywood talent agencies], and had supported the opposition candidates because they were saying that we should do that. It’s a democratic organization. Members showed up and voted resoundingly to continue the current course. And I think we’re all going to support it because that’s how it works. I’ve got concerns about it. I don’t mean to kind of immediately jump there, but I think there’s a sense of unease that all of us feel about what’s going on in the country. About what’s going on in the industry. My personal opinion is that, a lot of that anxiety has been focused on the agencies, [which] are involved in a number of activities that they shouldn’t have been. So I don’t fault at all the initial instinct to try and correct abuses that were happening in the agency business. My sense of it is, “Just how many battles can we fight at once? And there are other big battles coming, and should we try and resolve that?” I’m hoping that that’s what the current leadership’s doing.

A lot of the things that have worked very well for everyone over many, many years are not there anymore. ... [Residuals on the sale of foreign and domestic syndication rights are] disappearing because Netflix is that disruptive digital distribution technology where it’s worldwide, and they want to just buy you out. And the other companies are saying, “Well, that looks like a pretty sweet deal. Why can’t we have that?” And that means we’ve got to dismantle the entire rest of the residual formula and replace it equally with the same amount of money so that writers and actors, directors, can continue to be available. We have a freelance marketplace where people are available because they’re getting paid for the work they’re doing, but also they get paid enough to not be employed in those periods until they get employed again. If the industry doesn’t accept responsibility for replacing that residual structure to allow people to stay in the workforce, we’re going to be in a lot of trouble. A horrible game of musical chairs is going to start. Because there’s not enough bandwidth to maintain everything.

Look at the family on “Shameless.” The Gallagher family would probably be trying to steal the signal. But they would definitely have Netflix, because it’s cheap. And then, what else are you going to add to it? Are you going to add HBO? Netflix, HBO Max. Gee, I think I better have Disney+. Maybe I need Comcast. I think for most families, they’re not going to be able to maintain that. So there’ll be only so many that they do. And then there’ll be different bundles of who does what. And then the question is, when all that gets sorted out in a few years, how much money is coming to each and can they actually support their operations?

‘Everybody can’t continue to lose billions of dollars’

The biggest hurdle right now is that there’s so many shows that we have stretched the available workforce, experienced workforce, in every area. Not just writing, but in directing and elsewhere. And it’s great, because lots of people are getting new opportunities, many more people come up in the industry. But you’ve got a lot of people who aren’t experienced. Those of us who have long histories with lots of people have more opportunities to bring together experienced crews, because they know what their experience is going to be working with us. Much more difficult for people who are just hitting the market for the first time as a showrunner to pull the people together that they need to pull together. And then it will start to contract. I mean, [peak TV] will inevitably start to contract. Everybody can’t continue to lose billions of dollars. They will have to be profitable companies again at some point. And, as that happens, you do that by doing less and focusing more on what’s working for you. That’ll be a weaning, and that’s going to be unpleasant.

This story is part of the ongoing series Running the Show, in which The Times speaks with showrunners of your favorite TV programs about breaking into Hollywood, writers room secrets, being the boss and more challenges of the job.

TV

Running the Show

Yvonne Villarreal’s interviews with TV creators and showrunners

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.