How unlikely Steven Stucky proved indispensable to the L.A. Philharmonic’s rise

- Share via

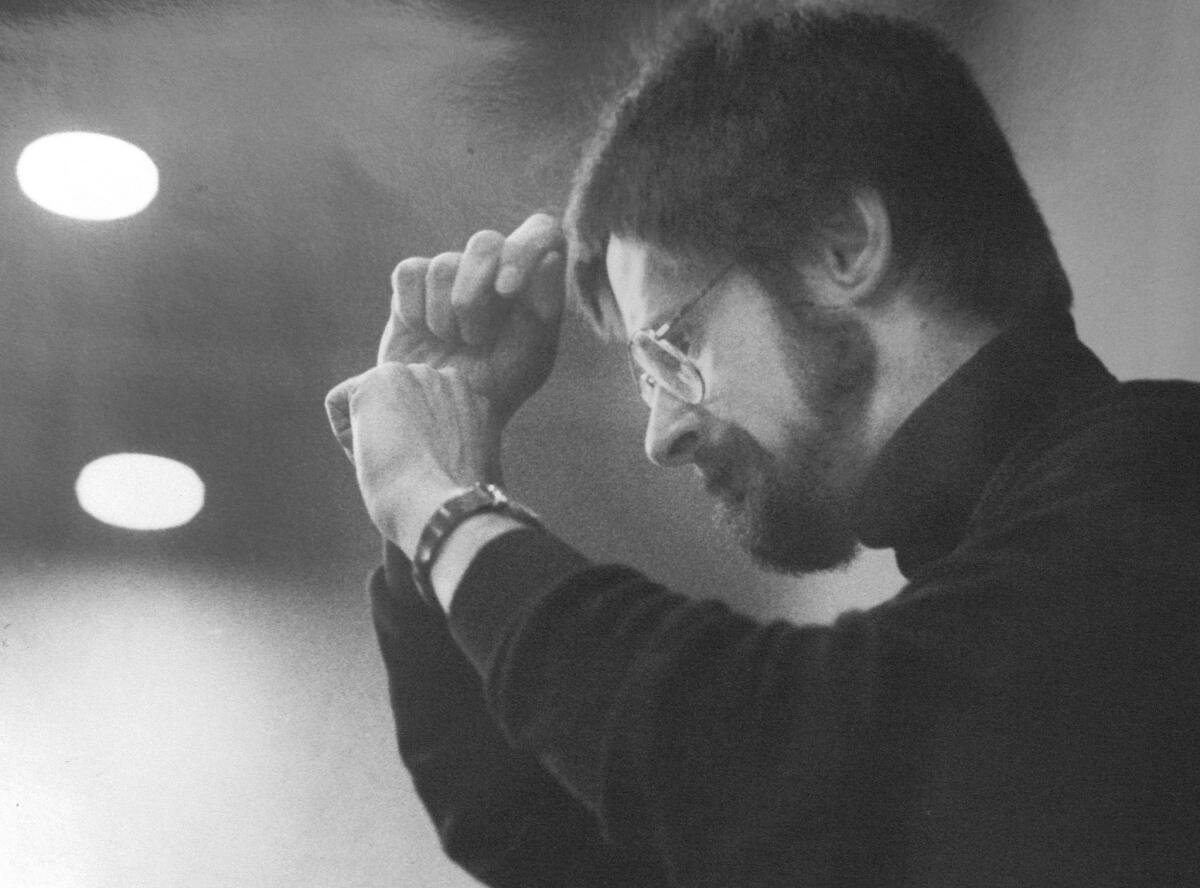

I first met Steven Stucky at Yaddo, the arts colony in upstate New York, in the summer of 1988. He was a 38-year-old composer just beginning to emerge on the national scene. He had been named composer-in-residence of the Los Angeles Philharmonic, and I had come to interview him for his first major newspaper profile. A native of Kansas who had grown up in Abilene, Texas, and taught at Cornell University, he agreeably combined an academic’s inner dry wit with a courteous aw-shucks veneer.

See more of Entertainment’s top stories on Facebook >>

I liked him instantly. But he had little experience with the West Coast or its music, and I couldn’t imagine his L.A. association ever amounting to much. The piece he was best known for, “Dreamwaltzes,” was a sentimental Neo-Romantic take on Viennese waltzes of yore. The L.A. Phil’s then music director, André Previn, had conducted it the previous year.

Who knew that this affably backward-looking, backwater nerdish composer appearing unworldly even in the Victorian setting of Yaddo would play an indispensable role in making the L.A. Phil the hippest and most progressive major orchestra in America? I didn’t. He certainly didn’t. Previn couldn’t possibly.

In fact, Stucky, who tragically died Sunday, turned out to be an essential ingredient in the secret sauce of the Southland’s new music ascendancy nationally and internationally. Death from an aggressive brain tumor seems hard to imagine, not for a brilliant brain like his that luxuriously processed information and allowed him to take delight in details the rest of us easily overlooked.

Stucky was a late bloomer as a composer. He was also a late bloomer as a composer-in-residence. He took his time. He did make an excellent first impression, but it was only gradually that we got to understand what he really had to offer. Slowly, painstakingly, he brought the L.A. community up to speed, graciously and wondrously encouraging curiosity about what was new in music. He always made it feel one on one.

Stucky’s formal involvement with the L.A. orchestra continued for 21 years, and he remained a member of the L.A. Phil family after that. Clashing with the administration over the direction of the orchestra, Previn resigned in 1989, and the appointment of Esa-Pekka Salonen made it seemingly out of the question for Stucky to remain. The orchestra wanted a new, non-Previn image. And no one seemed less likely a colleague for a young Finnish modernist than a Cornell-based Kansan known for aping Viennese waltzes.

That wasn’t really Stucky, though. “Dreamwaltzes” happened to be a one-off, a summery commission for the Minnesota Orchestra’s Sommerfest. The longing for the past may have been intentional, but Stucky surrounded the waltzes in wistful musical mists delicately reminding us that this is all an impossible dream.

Stucky did live in our time. He admired Witold Lutoslawski above all of his contemporaries and wrote an important book about the Modernist Polish composer. Proving conventional wisdom once more wrong, Stucky bonded with Salonen, who also looked up to Lutoslawski. The two young Luto-ites became and remained close friends. As a composer himself, Salonen obviously didn’t need a composer-in-residence, but he did need someone to guide him through the American and the L.A. scenes, and Stucky was his man.

By this time, Stucky had become immersed in West Coast music. While he continued to teach at Cornell, he became, in part anyway, one of us. He got to know everybody. He changed us, and we changed him. He gave the new music Green Umbrella series an alluring curatorial profile that has gone on to influence many other orchestras. He programmed music that he might not care for but that he believed needed to be heard. He then looked for ways to care for it. Steve Reich’s repetitions put him off, but not the energy, so he focused on the energy. He had an open mind and a big talent for persuasion. As his musical palate broadened, so did his music.

Everybody, and I mean everybody, liked Stucky. He wrote likable music too. It could be too likable, occasionally perceived as lacking in a strong stylistic profile, not always immediately identifiable as Stucky. But dig a little deeper. He went in for strong, bright orchestral colors, and the instrumental pigment has an inner grit that makes the sounds feel somehow alive and connected to the earth and the atmosphere. A gentleman composer, he consigned poignancy to the lower layers, which made the music all the more hauntingly expressive.

I was on the jury that gave Stucky the Pulitzer Prize in 2005. It was a tough panel, with little agreement among us. The leader was the brilliantly cantankerous composer Gunther Schuller, who automatically dismissed every piece I suggested as we worked down the alphabet through more than 200 applications.

It was my job to make the case for Stucky’s Second Concerto for Orchestra, since it had been commissioned by the L.A. Phil for the orchestra’s first season in Walt Disney Concert Hall, and I had reviewed the premiere. We had been at this for a couple of days, and everyone was tired. Stucky was known but not well known to most of the jury.

Yet a minute after we put on a recording of the Second Concerto, Schuller looked up from the score with a contagious expression of delight. Everyone instantly got over his own issues. We had a winner we could all happily agree on. Stucky brought us together.

Stucky’s last large-scale work was “The Classical Style,” a wacky, highly unlikely opera about dead white 19th century composers and musical analysis. It was given its premiere at the 2014 Ojai Music Festival. As he had 30 years earlier with “Dreamwaltzes,” Stucky looked back, this time in a hilarious pastiche.

With his knack for accomplishing the unlikely, Stucky now could proceed from the ridiculous to the wistful to the utterly profound. His touch remained light and amusing as ever. But he made a meditation on the life and death of a musical style into a meditation on life and death. Too much of the opera’s astonishing depth went unrecognized in Ojai’s juvenile production. Still, it was apparent that “The Classical Style” belongs to the tiny but important handful of great American comic operas, the kind that can gently help us get through the day.

Stucky’s death is a shock to our musical system, and it must not go unattended. Would somebody please record the Second Concerto for Orchestra already? It’s been more than a decade since its Pulitzer. We need an adult production of “The Classical Style.” Most of all, let the path Stucky paved in L.A. serve as an ongoing example to us and to all.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.