‘The Big Bang Theory’ is ending, but we shouldn’t let multi-cam sitcoms die. Here’s why

- Share via

In the beginning was the word and the word was “Lucy.”

In 1951, at the dawn of television, Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz brought forth a new form of comedy: the three-camera sitcom, performed live before a studio audience.

The legacy of “I Love Lucy” runs through the whole history of television, from “The Honeymooners” and “The Phil Silvers Show” to “All in the Family” and “The Jeffersons,” to “Mary Tyler Moore” and “Rhoda,” “Cheers,” and “Taxi,” ”Good Times” and “The Golden Girls,” “Friends” and “Seinfeld,” “Roseanne” and “The Bernie Mac Show” — and on beyond “The Big Bang Theory,” which exits television after 12 seasons on May 16, leaving behind its single-camera spinoff, “Young Sheldon.” (You will see it in reruns, however, for the rest of your natural life.)

Let us take a moment, then, to examine this durable form, often regarded as the emblem of TV witlessness — there is no lack of examples to make the case — but also the vehicle for some of the medium’s smartest, funniest, edgiest, most culturally resonant, socially relevant, warmly human and demographically far-reaching programs. (See the list above, just for a start.)

ALSO: ‘Big Bang Theory’ showrunner Steve Holland on ending the series: ‘Finales are hard’ »

Roughly as many people — in the high teens of millions — watch “The Big Bang Theory,” even off its peak, as watch “Game of Thrones,” also in its last season; yet the media treat “Game” as a miracle of television and “Big Bang” as just … television.

Here’s a fun experiment (some experience of television required): Take any single-camera comedy you like — “Veep” or “Brooklyn Nine-Nine” or “Fresh Off the Boat” — and imagine it remade multi-camera style, its sets reconfigured for a studio audience, with fewer locations (nearly all indoors), longer scenes and jokes modified for multi-camera’s serve-and-return rhythms.

Conversely imagine any multi-camera sitcom — “The Dick Van Dyke Show” or “2 Broke Girls,” “Cheers” or “Seinfeld” — remade single-camera style, its characters set down in a three-dimensional world, where the rooms have four walls, and there is no one laughing on the soundtrack who isn’t in the scene.

Either way, something essential is lost. Neither way is better.

And yet single-camera is generally regarded as the superior form, in part because edgier, more experimental, more “serious” comedies tend to be shot that way now, where the multi-camera sitcom is seen as ephemeral and old-fashioned — it all begins with “Lucy,” remember, nearly 70 years ago — even silly.

But multi-camera has also represented what’s new in situation comedy, with single-camera the creaky style it challenged.

ALSO: How NBC’s ‘Must See TV’ risk takers of the ’90s are still launching groundbreaking TV »

In fact, single-camera comedy was the dominant style through much of the 1950s and all of the 1960s. It came with a laugh-track attached, not just to make bad jokes pass for good ones — although that was certainly part of it — but also because people were used to watching comedy in a crowd, amid the sound of other people’s laughter. Not hearing laughter made things seem unfunny.

When in 1965 CBS experimentally aired “Hogan’s Heroes” minus a laugh track, they discovered that people preferred it added. (We have since learned to live without them; putting a laugh track on a single-camera comedy nowadays would be perceived as ironic, a meta-fictional joke about situation comedy.)

It was in the early 1970s that multi-camera comedy really took off, as Norman Lear launched a string of social-commentary comedies with “All in the Family” and MTM Productions went forth with the grown-up humor of “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” and “The Bob Newhart Show.” In those years, single-camera comedy was the form for safer shows like “Bewitched” and “The Brady Bunch.”

This new old form, which would define television comedy well into the present century, would of course produce plenty of dross and dreck, along with a wealth of well-executed, perfectly enjoyable middlebrow entertainments. But it came back to life as the intelligent alternative, a framework for sophisticated comedies that crackled with the energy of live performance — and surely paved the way for “Saturday Night Live.”

On the face of it, single-camera comedy is more “realistic,” which is to say, it is more like film than like theater. Yet there is nothing natural in how such shows are put together, in scraps, over days, with scenes shot out of order, the recording of any one scene proceeding in fits and starts and repeats, in master shots, and close-ups and reverse angles.

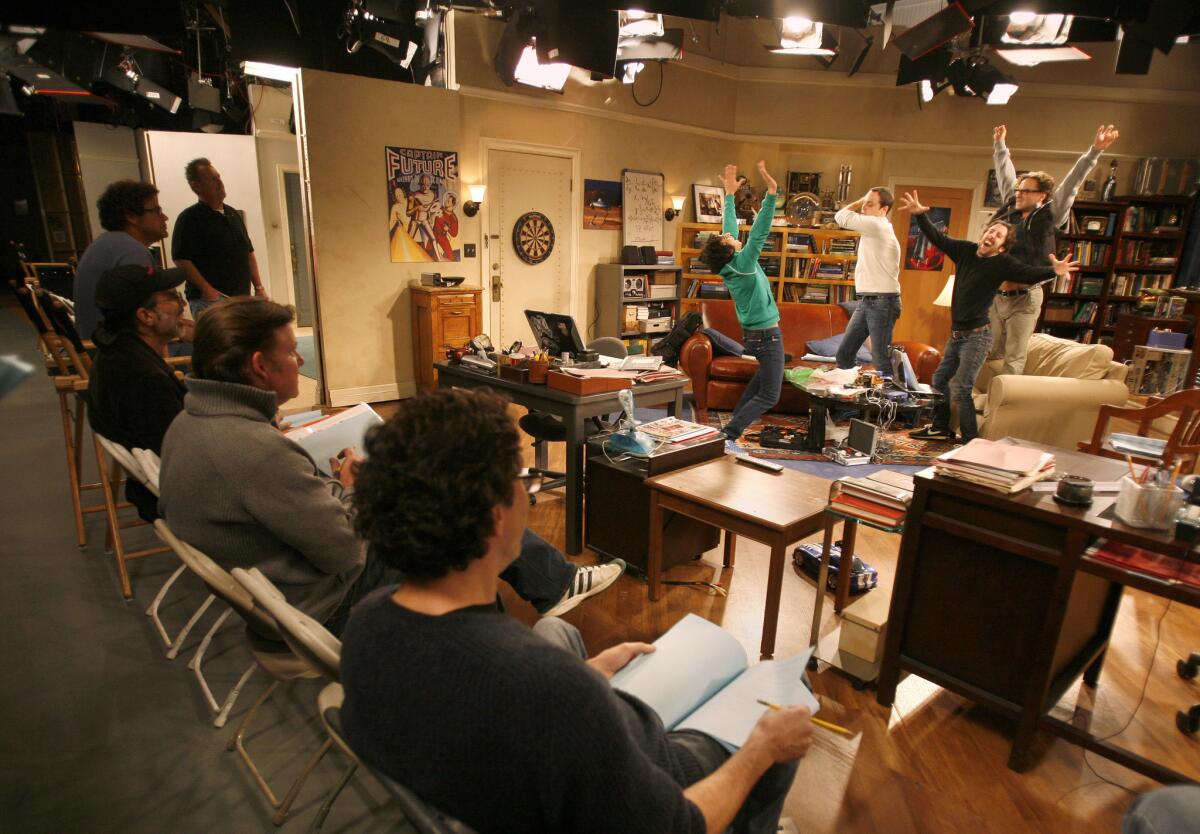

Multi-camera comedy, by contrast, is (more or less) the record of an event, chronological by nature, theatrical in its conventions. It is performed like a play, within the proscenium of your television screen. It feels live.

You know the arrangement: A door leads out at left or right; on the opposite wall, another door leads farther in. Perhaps some stairs at the back. Center stage, a couch, or maybe a bar, or some desks. An actor enters, and another. They interact in something like real time. An audience laughs, unseen but, mechanical sweetening notwithstanding, authentic. (After a single-camera first season, in 1970, “The Odd Couple” switched to multi-camera, in part because stars Tony Randall and Jack Klugman hated the laugh track; if there were to be laughs, they wanted them from real people.)

Multi-camera was the ideal medium for an age, not yet concluded, of shows built around stand-up comedians used to working before a live audience: Redd Foxx (“Sanford and Son”), Gabe Kaplan (“Welcome Back, Kotter”), Tim Allen (“Home Improvement,” the current “Last Man Standing”), Freddie Prinze (“Chico and the Man”), Bill Cosby (despite the failings of the man, it’s pointless to deny the power of “The Cosby Show”), “The Bernie Mac Show” and, more recently, with various degrees of success, Whitney Cummings, John Mulaney and Jerrod Carmichael, in shows all named for their leads.

These new voices pushed TV comedy in new directions. Robin Williams’ compulsive improvising on “Mork and Mindy” led producer Garry Marshall to add a fourth camera to the historical three in order to keep track of his restless star. The meta-sitcom “It’s Garry Shandling’s Show” integrated the studio audience into the action — one might say it broke the fifth wall — while “Seinfeld” added speed and complexity to a show that has always struck me as a burlesque turn on Greek tragedy in which fate always wins.

“Roseanne” brought downbeat gravity to the family comedy. And Ellen DeGeneres’ coming out as gay on “Ellen” would have meant less — though, of course, still a lot — without an audience there to share the moment.

Where a single-camera comedy might home in on small details — a lost earring, a date on a calendar, a carton of milk no one suspects has gone bad — to tell a story or set up a gag, or travel into the world outside the soundstage, multi-camera comedy just looks at people, at close quarters, talking, talking, talking. It tells stories of humans getting along or not getting along in a shared space — a whole, a workplace, a bar — with the fact that they’re sharing a space perhaps more important than whether or not they’re getting along in it.

REVIEW: NBC’s ‘Abby’s’ brings a ‘Cheers’ vibe with a dash more flavor »

That is exactly the theme of a show like “Cheers” and its recent descendant from “The Good Place’s” Mike Schur — “Abby’s” — which puts a new twist on the bar-centered multi-cam setup by being shot and set outdoors.

This space is shared with the viewer too. To laugh at home with a studio audience is to become a member of that audience; the fourth wall is whatever wall’s behind you. You become a witness, a participant, family. The Conners, the Cranes, the Bunkers, the Huxtables; Jerry and George and Elaine and Kramer; Sam and Diane and Norm and Cliff and Woody and Carla; Anne, Julie, Barbara and Schneider from the original “One Day at a Time” and Lydia, Elena, Alex, Penelope and Schneider from the recent one; Sheldon and Leonard and Penny and Raj and Howard and Bernadette and Amy, you are all one in virtual space and time. There has never been a sitcom title truer than “Friends.”

Follow Robert Lloyd on Twitter @LATimesTVLloyd

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.