Critic’s Notebook: A mother lode of Huell Howser memorabilia

- Share via

Not long ago, I went down to the city of Orange (founded 1869, incorporated 1888) to Chapman University, in search of the late Huell Howser.

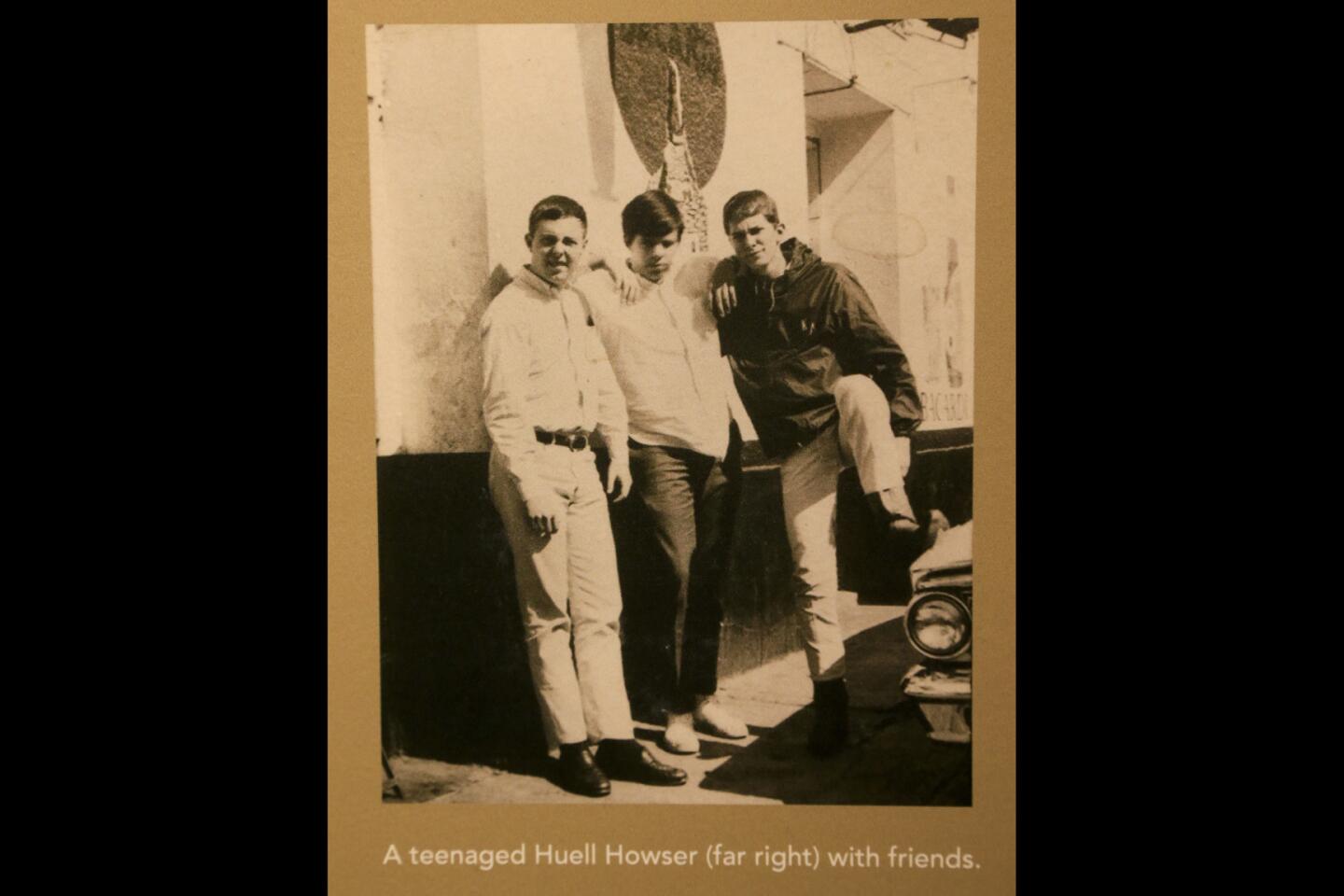

Howser died in January 2013 at the age of 67, having publicly retired a few months earlier from what was still a busy career as a roving video reporter. His series, including “California’s Gold,” “California’s Green,” “Visiting,” “Road Trip,” “Downtown” and “The Bench,” were fixtures on public television across the state; his face family-familiar, his Tennessee accent much imitated, sometimes mockingly, more often with affection.

I knew him a little, but many who never met the man felt close to him. A combined search of the terms “Huell Howser” and “beloved” produced 112,000 hits.

Howser liked Orange, where the old fountain still burbles at the center of the old plaza. And he liked Chapman, whose president, James L. Doti, became a friend after Doti hand-wrote a letter protesting Chapman’s absence from a piece he did on the town. He would occasionally guest-lecture at the school and meet Doti for lunch on trips between his Los Angeles apartment and his house in Twentynine Palms.

And when he died — or rather, when he knew he was dying — he arranged to leave his estate to the university: his tapes, his papers, his found-object artworks, a couple of houses and a good deal of money. The money and the profits from the sale of one of the houses went to endow a scholarship, called the California’s Gold Scholarship. The other house, a 1968 space-age curiosity nestled atop a small volcano cone in the desert near Barstow, remains in the possession of the school, which will use it as a kind of educational outpost.

The tapes and art and representative bits of memorabilia have become the basis of a public archive — accessible in person at Chapman and available online — and a permanent exhibit, co-sponsored by the Southern California Auto Club, called “That’s Amazing! Thirty Years of Huell Howser and California’s Gold.” Located in a converted computer lab in the basement of the school’s Leatherby Libraries, it is the sort of place that Huell Howser might visit, if its subject were anything other than Huell Howser. He was serious about his work, but modest about his accomplishments.

Still, it’s fitting that there should be such a place and that, for many, it will involve making a trip to a place they otherwise might never have seen. That is very Huell.

I met President Doti in his office at Memorial Hall, the focus of what might be called the old school, whose columned buildings gather around a grassy quadrangle, open at one side to a street of Craftsman bungalows. Originally the site of Orange Union High School, before Chapman took it over in 1954, it feels cozy and classic, like something out of an Andy Hardy film.

A compact, trim, quick-moving man, Doti is an economist by training (and, he happened to mention, a sometime actor on the soap opera “The Bold and the Beautiful,” whose producer is a Chapman alumni).

“He was one of my heroes,” he said of Howser as we half-sprinted past newer buildings to the library. “I’m from Chicago and when I came here I learned more about California just watching his show; I was able to vicariously travel around the state and meet interesting places and people through him. And then to meet him and find out what a warm and engaging and smart and creative person he was just attested to why his show connected to me, and to so many other people.

“He came to see me and he said, ‘I’m putting my estate plans together and I’d like to give everything to Chapman.’ I was shocked, I didn’t know he was ill, he looked fine. But I could see he was very emotional, so I thought maybe it was something.”

We went down to the library basement. Tucked into an alcove at the bottom of the stairwell was an arrangement of some of Howser’s found art — re-contextualized industrial castoffs that, like his programs, are the work of an eye drawn toward humble or hidden things, that found amazement where many would not bother even to look. On the wall outside the entrance to the exhibition space was a quote referring to the scholarship fund: “A hundred years from now, long after people have forgotten me and my television show, the words California’s Gold will mean those students who are the future of the world.”

Doti recalled lunches where “we just talked about what we would do over at the Volcano House. I could see it brought so much pleasure to him to think about students studying there. He said, ‘I bought that on a whim and in 10 years I went there twice. But when it became for educational purposes, it seemed like serendipity — so there had to be something to that whim that would lead to this, that it was all meant to be, for me to come here and fall in love with this place.’”

Doti handed me off to Sheryl Bourgeois, the university’s executive vice president of university advancement, marketing and communications. “Sheryl’s really the one who helped organize this exhibit all the presentations,” he said, and rocketed back up the stairs.

Bourgeois, who had grown close to Howser over months of combing through his things, considered her work with the estate to be a “labor of love.”

“He was a very private person,” she said, “and he didn’t want this to be about Huell Howser. He was really opposed to the notion of a memorial, and had told us close to his passing, ‘Please, I don’t want some sobby recount of my life.’”

The exhibit opened March 29 to about 4,000 visitors. “It was kind of like Disneyland on a really busy day,” Bourgeois said. “People waited for almost three hours, and we only gave them 15, 20 minutes to walk through. They were taking pictures of everything.” In Memorial Hall, there were screenings of “A Golden State of Mind — The Storytelling Genius of Huell Howser,” a documentary by faculty member Jeff Swimmer. (It will screen again there Sept. 20.)

Created by the Pasadena-based Hunt Design, the space is compact and colorful and full of things to see, without seeming crowded; it is busy, yet it invites contemplation. Beyond is a study room with computer terminals to view the collection and, beyond that, the archives themselves, where the tapes and papers and a portion of Howser’s library are kept.

On the floor of the exhibit is a map of California highlighting places Howser visited. A wraparound mural presents a timeline of his life and career; illustrated pillars recall places he went and people he met. A re-creation of his office is as tidy as it would have been in life.

“He was a very simple guy, very clean,” said Bourgeois, “and so he knew where everything was and he didn’t waste a lot of time.”

There is a hand-drawn calendar from some distant August, its entries oddly poetical: “dune buggy,” “wart hog update,” “summer ice,” “sea shadow.”

A glass case holds Howser’s camera and microphone, another displays a selection of memorabilia, including art by Slater Barron, the Lint Lady; a John Romita drawing of Howser, Marvel Comics chief Stan Lee and Spider-Man; a rivet from the Golden Gate Bridge; the Olympic Torch that Howser carried in the run-up to the 1996 Summer Olympics; a milk bottle from Broguiere’s Dairy bearing his likeness beneath the legend “Favorite Visitor”; a much-autographed “Simpsons” script (Howser played a version of himself on the series); a seismographic print of his voice speaking the phrase “California’s Gold”; and his parents’ movie camera.

“We found this box full of awards,” Bourgeois remembered. “He had none of them out.”

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.