How a Nashville pastry chef’s memoir meets our moment

- Share via

One wild thing about signing a book deal is that after the writing and editing and designing have been completed, an author can never quite predict what the cultural climate will be when a publisher finally releases a book into the world.

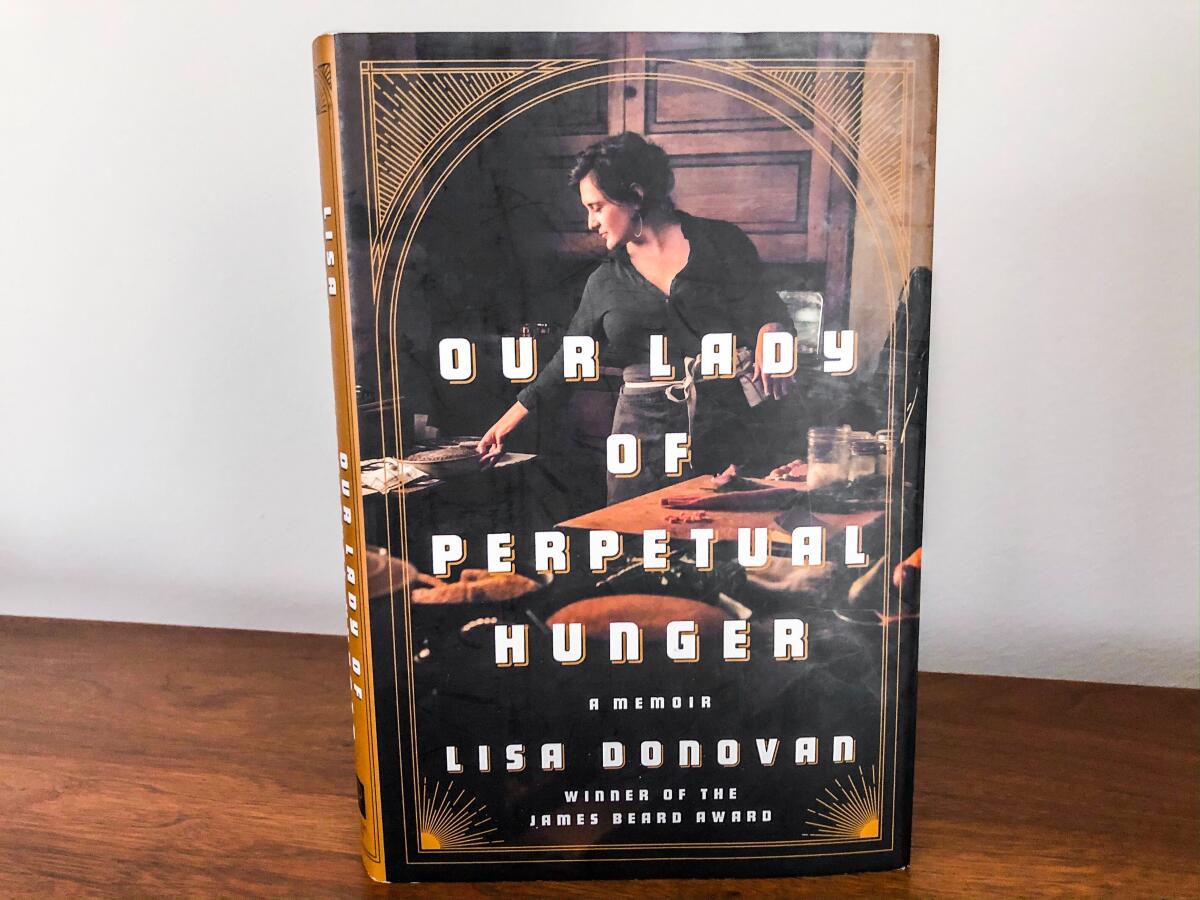

Lisa Donovan’s first memoir, “Our Lady of Perpetual Hunger,” was released this month in the middle of a singular maelstrom in American history. Yet its arrival — with themes of personal reckoning and reclamation, gender inequity (specifically the treatment women have endured to succeed in professional kitchens) and the country’s racial caste systems, as enacted within her own family — feels as if it was written for the moment.

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

Donovan became rightly known last decade as one of the South’s best pastry chefs: In the late 2000s and early 2010s, when restaurant desserts were going through a deconstructed, many-moving-parts phase, she distinguished herself in Nashville with a style that was, in many definitions of the word, wholesome. With gigs at City House, Margot Cafe & Bar and, most famously, as Sean Brock’s pastry chef at Husk, she became known for her versions of chocolate church cake, Carolina Gold rice pudding and especially her buttermilk chess pie, adorned with whatever fruits came from local orchards.

I was writing about food in the South when Donovan’s pastry career was on the rise. I’d eat in the restaurants where she baked, plotting my dinner order in a way that I’d still have room for every dessert on the menu that night. A lot of us did this.

After 15 years developing her voice through baking, she left restaurants and began to concentrate on writing. She won a James Beard Award in 2018 for her Food & Wine article “Dear Women: Own Your Stories.” It began with some bullet points about who she was:

“1. I have been violently raped by a man whom I trusted.

2. I had to have an abortion because of this rape.

3. I had to listen while people I loved told me it was my fault and that I would ruin his life by claiming this out loud … ”

“Our Lady of Perpetual Hunger” expounds on that essay (the man about whom she wrote in the magazine article was a college-age boyfriend) and goes much further. Donovan connects her childhood (including the ways her grandmother’s Mexican-Zuni heritage framed dynamics in the family) to building her own family. (I recognize the particular Southern trait of referring to her husband, John Donovan, by his full name throughout the book.) She names names in chapters about her time in restaurants, but she doesn’t indulge in salacious gossip: She recounts shameful pay disparity and misogynistic kitchen culture to shine a light — to help point ways forward for an industry whose entrenched leadership styles and financial structures need to be rebuilt from the ground up.

I spoke with Donovan this week about writing the book and how its framing dovetails with the issues at hand in our country.

At what point did you know that you wanted to write this book? Where were you in your life?

When I left Husk in 2014, I ended up having a little bit of a — not necessarily crisis, per se, but I definitely was reckoning with myself about the things that I had been investing my energy in. I always knew I wanted to be a writer, that I could commit myself to the kitchen and still find a way to write.

Stepping away then from the restaurant business, I wanted these two defining interests to live together for a while. I assumed that I’d be writing about foodways and food traditions while also talking about the ways my generation came up in the South. Giants like Ruth Reichl and Gabrielle Hamilton have set beautiful examples about how to have conversations about their lives through food.

Did I think I was going to write a book that necessarily needed to talk about rape or abortion? No. But when I had this moment of reckoning with myself about the quality of experiences I was having versus my expectations, I realized quickly that for women, a lot of our stories — we carry them very privately. These are things I hadn’t even told my mother or my best friend; it took me years to tell my husband everything about the experiences I’d had.

And it took a lot for me to even admit to myself — through learning about pay disparities, or colleagues second-guessing my intentions around working because I was a wife and a mother, or making assumptions about my relationship to my boss — that I faced obstacles solely because I was a woman in the restaurant world.

Then I started coming across younger women who didn’t understand the sort of sweep-it-under-the-rug, put-your-head-down-and-keep-working-through-it way of thinking. I thought I was being subversive just by being present in a system that treated women unequally. I was fool enough to think I could change it by engaging in it. But I realized I should be following the example of younger women who were saying, “Actually, no, I’m not going to participate in any of this. I’m going to go over here and create my own way.”

How has it been to put out a book at a time when a pandemic has pushed so many of our country’s systemic failures to the forefront? I’m thinking, as one example, your story about [writer and food activist] Alice Randall having a kind, instructive conversation with you about obscured origins of Lowcountry Southern recipes — namely, the Gullah traditions and the innovations of enslaved cooks on which many dishes are based.

Beyond Alice’s generosity, I included that story hoping that it also speaks to the larger conversation of how women so deeply carry each other through this world.

So much in the media right now centers around workers’ rights and making jobs in the restaurant industry more financially sustainable — it’s everything that I say in the book and before the book was published.

It’s why Sean [Brock] and I got into social media fights with each other publicly because I was so angry about the conversations no one was having at the time about how workers and laborers were being treated in restaurants. There are parts of this book that transcend a gender narrative and go straight to the heart of the nature of essential workers and how we take care of workers — or not — in this country. It goes far deeper than what one boss paid one worker a long time ago. It’s much more about the survivability and sustainability and functionality of an industry.

I think for anyone that has looked at the model of restaurants in other countries, they realize why it’s so hard to survive as a restaurateur or chef-owner in America. Restaurants can’t meet slim margins in part because of the government’s failure around [the expense of private health insurance].

Your talent as a writer is as evident as your gifts as a pastry chef. I can so directly recall your desserts, the tang of buttermilk chess pie paired with fresh Georgia peaches. There’s a selfish sadness for me that you became so stellar in restaurants and then, for the soundest of reasons, you decided the food industry ultimately wasn’t for you.

Well, thank you. And it’s true, I did decide that. If we look at life in sort of a bifurcated first half and second half, I’ll be lucky if, at 42 years old, I get another 42 years. If I have my druthers that means sitting down at my desk every day and writing — and selling a screenplay, selling a novel. I’m brimming with the energy and enthusiasm I remember from when I was first teaching myself to bake. I’d wake up in the middle of the night and test a recipe or write a menu because I had a dream about it.

Even during a scary time in the world, I know that I’m going to keep putting one foot in front of the other and approaching work and life the way that I always do: I make it up as I go.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

L.A. Food Bowl returns ... in virtual form

The Los Angeles Times Food Bowl, usually held as a monthlong series of events in May, is being held this fall in virtual form, with World Central Kitchen and the Los Angeles Regional Food Bank as partners. Events include a cook-a-thon fundraiser Oct. 17; cooking editor Genevieve Ko, cooking columnist Ben Mims and senior food writer Jenn Harris will cohost 30 chefs and celebrities from Los Angeles, the nation and the world. The Food team compiled an accompanying guide for the year’s theme, “Takeout and Give Back.”

Closer at hand, an L.A. Times Dinner Series kicks off Sept. 5 with a three-course collaboration meal between Jon Yao of Kato and Mei Lin of Nightshade; the menu includes dry scallop porridge and pork belly ssam. Dinners will be picked up on the day of the event, and my colleague Lucas Kwan Peterson will host a video chat with the chefs while participants dine together online.

Have a question for the critics?

Our stories

— I write about World Central Kitchen’s team-up with chefs in Beirut to feed the city during its crisis (and also include some key places to donate).

— Ben Mims weighs in on a new cookbook that teaches us about foods that make us feel good: “Help Yourself: A Guide to Gut Health for People Who Love Delicious Food” by author Lindsay Maitland Hunt. (There’s also a recipe for spiced meatball and escarole soup.)

— Ben also spotlights a welcome, refreshing and early arrival to the farmers markets: passion fruit.

— Gamboge, a Cambodian-inspired deli and market, is open in Lincoln Heights … and other news from Garrett Snyder.

— Jenn Harris profiles Jessica Woo, who became a TikTok sensation making bento box lunches for her kids.

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.