‘Guilty. Thank you God.’ A victim’s brother sketches the Grim Sleeper trial

- Share via

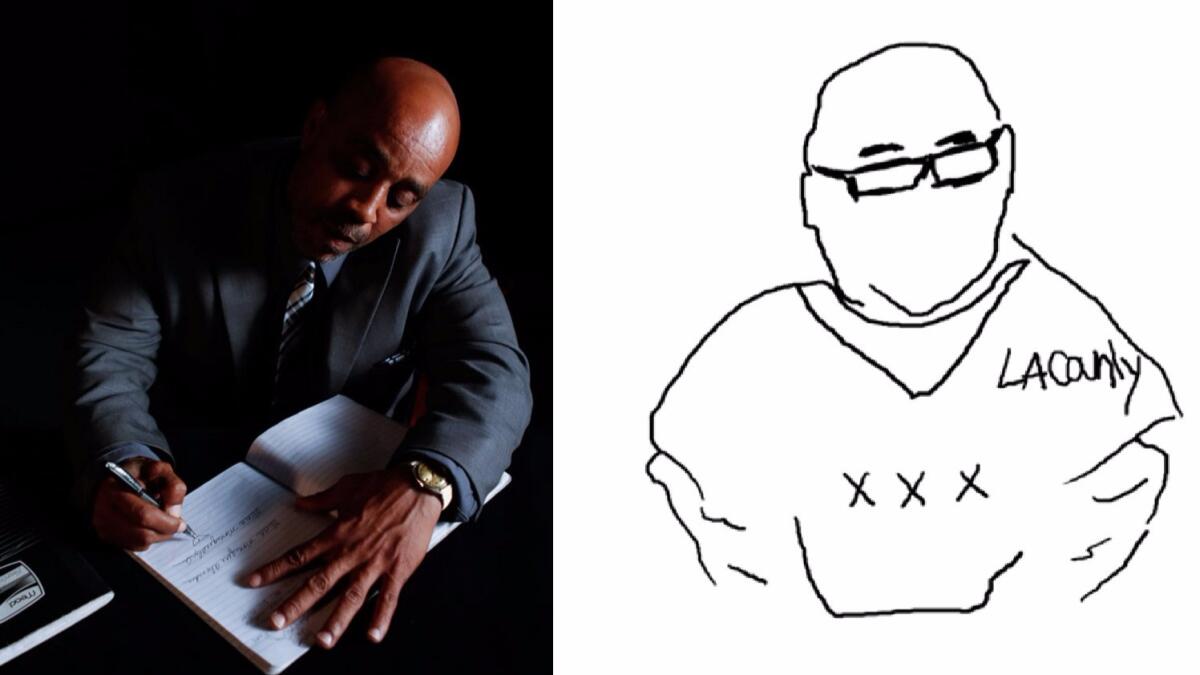

Donnell Alexander’s pen smoothly sketched a torso on a fresh page as he listened to the witness describe a woman’s murder 30 years earlier.

A pathologist was explaining in excruciating detail how a bullet had followed a downward trajectory as it tore through the front of a woman’s chest. On Alexander’s notebook, the outline of a bullet took shape, hovering above the body. Thin lines marked its path through an oversized heart.

Day after day, for nearly three months, Alexander sat in the audience of a downtown Los Angeles courtroom, driven by a deep personal need to see what would happen to the man accused of being the serial killer known as the Grim Sleeper.

Each morning, he brought his blue gel pen and composition notebook. He called them his “security blanket,” a comfort against the horrors being revealed.

His drawings on the lined pages created a rough chronological catalog of the trial’s gruesome evidence: The bodies sprawled in alleys across South Los Angeles. The guns found by police. The man seated at the defense table, accused of murdering 10 women.

The sketches were rough; Alexander does not pretend to be an artist. But he tried to capture on paper the stories that have unfolded in court about the deaths of the women.

All but one.

::

Growing up in their home on 69th Street, Donnell and his sister would sit for hours at the foot of a picture window. They ripped out photographs from magazines and held them to the bright windowpane, tracing the edges of the images onto blank pages.

Alicia traced ballerinas and dancers. Donnell, seven years older, drew football players and boxers.

There was a peace inside the South L.A. house that was not found outside their window. It was the 1980s, and violent gangs were taking control of the neighborhood. The crack cocaine epidemic was emerging.

Their father shielded his five children as best he could. He took them ice skating at a rink in Lomita. He bought a horse that he kept at a farm in Chino, where the family spent weekends riding and caring for the yearling named Conquest. He ran a youth football league, and his boys played all over L.A. County.

Alicia was an aspiring equestrian, a figure skater, a cheerleader. She was kind and selfless, beautiful and serene, Alexander recalled.

Alexander and his two brothers always looked out for her. The star athletes were well-known locally, and people knew not to mess with their baby sister.

But as she grew older, she was drawn to the world outside and they couldn’t keep an eye on her every move. She became rebellious, staying out late and sometimes not coming home until the next morning, Alexander recalled. They suspected she was using drugs.

In September 1988, she disappeared. Her family called around, asking neighbors whether they had seen her. No one had.

A few days later, Alexander received a message to head home. He arrived to see his father pacing in the yard, weeping.

Alicia’s naked, decomposing body had been found under a mattress in an alley. A sweatshirt was knotted around her neck. She was 18.

::

Nearly three decades later, Alexander’s father strode to the witness stand in the downtown courtroom. He locked eyes with the prosecutor as she asked him whether he knew someone named Alicia Monique Alexander.

“That’s my … that’s my baby daughter,” he said.

Alexander, 52, drew his father’s figure on the corner of a page.

His hand moved quickly. The sketch had little detail other than the older man’s big spectacles and bushy mustache. The page was soon covered in drawings of relatives of other victims identifying their daughters and sisters — and in one case, a mother — in court.

They, like Alexander and his family, had waited years before Los Angeles police linked the deaths to a serial killer and made an arrest. The delay led to outrage that many in South L.A. attributed to police indifference to the victims, who were all young black women.

For years, the family wondered if Alicia’s killer was someone they knew, someone who still lived nearby. They obsessed over what they could have done differently.

“It was the worst feeling in the world for my brothers and I to know that our sister was found raped and dead in an alley on our watch,” Alexander said.

The family leaned on their Christian faith to get through the uncertainty, clinging to their belief that one day that police would find her killer.

Then, 28 years later, Lonnie Franklin Jr. sat a few feet away, on trial for Alicia’s murder.

Alexander and his relatives always took seats in the gallery’s second row. They were among the few who attended nearly every hearing since Franklin was charged in 2010.

The routine soothed their pain, Alexander said. He quit his job as a maintenance supervisor at Baldwin Hills Crenshaw Plaza mall so he could go to the trial. The family attended out of devotion to Alicia’s spirit.

“The only time she comes alive is when she’s mentioned in court,” Alexander said. “He took my sister’s life, but he didn’t kill our family’s love.”

His ritual of sketching began after most reporters stopped showing up and TV cameras were banned from the courtroom. He was inspired by a professional courtroom artist who covered the trial for a few days. He noticed how her sketches caught the emotion in the room. Alexander hadn’t drawn since he was a child, but he thought sketching might keep his mind active during dull stretches of testimony.

He often drew Superior Court Judge Kathleen Kennedy, the most prominent figure in the courtroom. He sketched the necklaces she wore atop her robes, the nick-knacks on her bench and a colorful painting that hung behind her.

His portfolio included several drawings of the backs of the attorneys’ heads; they rarely turned to the audience long enough for Alexander to capture their faces. There was a depiction of LAPD Det. Daryn Dupree, a handsome, 26-year department veteran and the last remaining detective on the case. Alexander doesn’t plan to show Dupree the drawing, which unintentionally depicts him with a somewhat lumpy face.

“I use a pen, so I can’t erase,” he said.

Retired LAPD Det. Dennis Kilcoyne, who once led the Grim Sleeper investigation, caught a glimpse of his own mustachioed caricature when he walked by Alexander after his testimony. “Don’t quit your day job,” he quipped, to laughter from the family and shushes from the bailiff.

Alicia’s name was sometimes written in the notebook, but Alexander never drew her. On the first day of the trial, a photo of her naked corpse was shown on a projector. Her mother covered her teary eyes and collapsed into her husband, who buried his head in his hands and wept.

The prosecutor at times gave the family a discreet nod whenever a photo of her was about to be shown so they could decide if they wanted to leave.

On a recent day when testimony focused on seven of the victims, Alexander wrote their names in large letters on one page: Debra Jackson, Henrietta Wright, Barbara Ware, Bernita Sparks, Mary Lowe, Lachrica Jefferson and lastly, Alicia Alexander.

In big, bold strokes he wrote: “ALL WERE KILLED BY ... SAME FIREARM.”

The gun was the piece of evidence that prosecutors said tied Franklin to Alexander’s sister. The seven women were killed by bullets fired from the same .25-caliber handgun. Three of the women had Franklin’s DNA on their bodies. Alicia’s body was too badly decomposed to retrieve DNA.

Other victims were linked to Franklin through additional DNA and ballistics evidence, prosecutors alleged.

Alexander sketched furiously one day as the prosecutor played a video for the jury. On a large projector screen in the courtroom, an LAPD detective was shown placing photographs of women on a table in front of Franklin. One was of Alicia, with a shy smile, long bangs and a side ponytail.

During the video-recorded interview, two detectives sat across from Franklin and explained that the women had been murdered.

“I haven’t killed anybody,” Franklin answered. He denied having met any of the women.

In the courtroom, Alexander shook his head.

“Lies, Lies, Lies,” he wrote in the notebook.

::

Alexander used thick strokes to trace Franklin’s scowl, his black eyeglasses and his slouch. The side profile was repeated several times in the notebook, often drawn alone on a page.

In the minutes before the verdict Thursday, Alexander realized he’d forgotten his notebook at home and scrambled to find paper and pen.

He drew Franklin one last time, capturing the slumped posture, the drooping face. But this time, the drawing of his sister’s killer was soon surrounded by the words of the court clerk, who read aloud the jury’s findings.

He turned the page over, his eyes welling as he wrote.

“Alicia M. Alexander ... Guilty.”

He added: “Thank you God.”

Twitter: @sjceasar

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.